Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Patients Characteristics

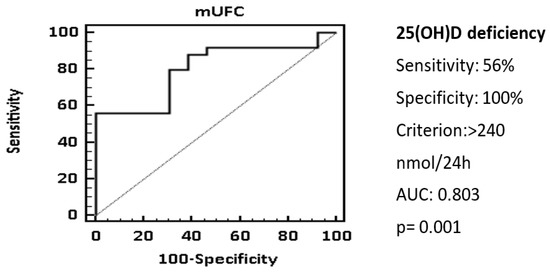

2.2. Identification of miRNAs Differentially Expressed in Corticotroph Adenomas Causing CD and Subclinical Cortiotroph Adenomas

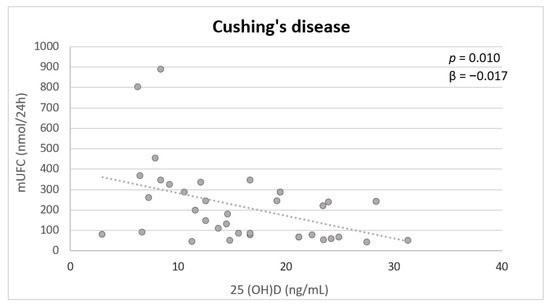

2.3. The Correlation of miRNA Expression and Patients’ Clinical Data

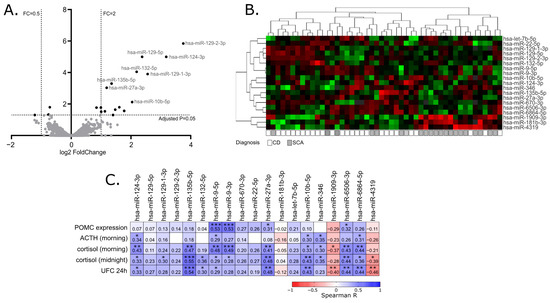

2.4. Funtional Enrichment Analysis of Differentially Expressed miRNAs

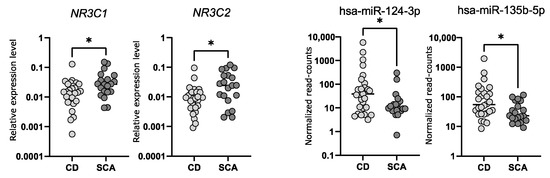

2.5. Comparison of the Expression of NR3C1 and NR3C2 in Corticotroph Adenomas Causing CD and Silent Adenomas

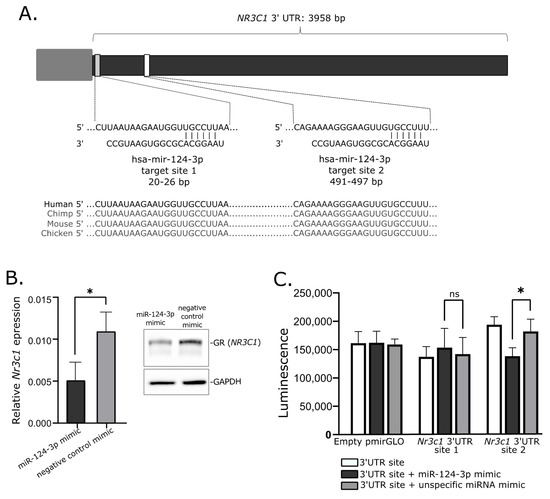

2.6. Investigtion of miRNA-Related Regulation of NR3C1 In Vitro

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Patients and Tissue Samples

4.2. Micro RNA Expression Profiling

4.3. qRT-PCR gene Expression Analysis

4.4. Cell Line Culture and miRNA Mimic Transfection

4.5. Luciferase Reporter Gene Assay

4.6. Western Blotting

4.7. Statistical Analysis

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ben-Shlomo, A.; Cooper, O. Silent Corticotroph Adenomas. Pituitary 2018, 21, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitale, G.; Tortora, F.; Baldelli, R.; Cocchiara, F.; Paragliola, R.M.; Sbardella, E.; Simeoli, C.; Caranci, F.; Pivonello, R.; Colao, A. Pituitary Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Cushing’s Disease. Endocrine 2017, 55, 691–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kontogeorgos, G.; Thodou, E.; Osamura, R.Y.; Lloyd, R.V. High-Risk Pituitary Adenomas and Strategies for Predicting Response to Treatment. Hormones 2022, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osamura, R.Y.; Grossman, A.; Korbonits, M.; Kovacs, K.; Lopes, M.B.S.; Matsuno, A.; Trouillas, J. WHO Classification of Tumours of Endocrine Organs, 4th ed.; Lloyd, R.V., Osamura, R.Y., Rosari, J., Eds.; IARC Press: Lyon, France, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, S.; Chen, X.; Wu, Y.; Wang, R.; Bao, X. An Update on Silent Corticotroph Adenomas: Diagnosis, Mechanisms, Clinical Features, and Management. Cancers 2021, 13, 6134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tateno, T.; Kato, M.; Tani, Y.; Oyama, K.; Yamada, S.; Hirata, Y. Differential Expression of Somatostatin and Dopamine Receptor Subtype Genes in Adrenocorticotropin (ACTH)- Secreting Pituitary Tumors and Silent Corticotroph Adenomas. Endocr. J. 2009, 56, 579–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabalec, F.; Beranek, M.; Netuka, D.; Masopust, V.; Nahlovsky, J.; Cesak, T.; Marek, J.; Cap, J. Dopamine 2 Receptor Expression in Various Pathological Types of Clinically Non-Functioning Pituitary Adenomas. Pituitary 2012, 15, 222–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Righi, A.; Faustini-Fustini, M.; Morandi, L.; Monti, V.; Asioli, S.; Mazzatenta, D.; Bacci, A.; Foschini, M.P. The Changing Faces of Corticotroph Cell Adenomas: The Role of Prohormone Convertase 1/3. Endocrine 2017, 56, 286–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohta, S.; Nishizawa, S.; Oki, Y.; Yokoyama, T.; Namba, H. Significance of Absent Prohormone Convertase 1/3 in Inducing Clinically Silent Corticotroph Pituitary Adenoma of Subtype I—Immunohistochemical Study. Pituitary 2002, 5, 221–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tateno, T.; Izumiyama, H.; Doi, M.; Akashi, T.; Ohno, K.; Hirata, Y. Defective Expression of Prohormone Convertase 1/3 in Silent Corticotroph Adenoma. Endocr. J. 2007, 54, 777–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tateno, T.; Izumiyama, H.; Doi, M.; Yoshimoto, T.; Shichiri, M.; Inoshita, N.; Oyama, K.; Yamada, S.; Hirata, Y. Differential Gene Expression in ACTH -Secreting and Non-Functioning Pituitary Tumors. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2007, 157, 717–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagaya, T.; Seo, H.; Kuwayama, A.; Sakurai, T.; Tsukamoto, N.; Nakane, T.; Sugita, K.; Matsui, N. Pro-Opiomelanocortin Gene Expression in Silent Corticotroph-Cell Adenoma and Cushing’s Disease. J. Neurosurg. 1990, 72, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raverot, G.; Wierinckx, A.; Jouanneau, E.; Auger, C.; Borson-Chazot, F.; Lachuer, J.; Pugeat, M.; Trouillas, J. Clinical, Hormonal and Molecular Characterization of Pituitary ACTH Adenomas without (Silent Corticotroph Adenomas) and with Cushing’s Disease. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2010, 163, 35–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neou, M.; Villa, C.; Armignacco, R.; Jouinot, A.; Raffin-Sanson, M.L.; Septier, A.; Letourneur, F.; Diry, S.; Diedisheim, M.; Izac, B.; et al. Pangenomic Classification of Pituitary Neuroendocrine Tumors. Cancer Cell 2020, 37, 123–134.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bujko, M.; Kober, P.; Boresowicz, J.; Rusetska, N.; Paziewska, A.; Dabrowska, M.; Piaścik, A.; Pȩkul, M.; Zieliński, G.; Kunicki, J.; et al. USP8 Mutations in Corticotroph Adenomas Determine a Distinct Gene Expression Profile Irrespective of Functional Tumour Status. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2019, 181, 615–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vreugdenhil, E.; Verissimo, C.S.L.; Mariman, R.; Kamphorst, J.T.; Barbosa, J.S.; Zweers, T.; Champagne, D.L.; Schouten, T.; Meijer, O.C.; De Ron Kloet, E.; et al. MicroRNA 18 and 124a Down-Regulate the Glucocorticoid Receptor: Implications for Glucocorticoid Responsiveness in the Brain. Endocrinology 2009, 150, 2220–2228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sõber, S.; Laan, M.; Annilo, T. MicroRNAs MiR-124 and MiR-135a Are Potential Regulators of the Mineralocorticoid Receptor Gene (NR3C2) Expression. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010, 391, 727–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xu, H.; Wang, Y.; Shen, C.; Ma, L.; Zhao, C. MicroRNA-124a Contributes to Glucocorticoid Resistance in Acute-on-Chronic Liver Failure by Negatively Regulating Glucocorticoid Receptor Alpha. Ann. Hepatol. 2020, 19, 214–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.N.; Tang, Y.L.; Ke, Z.Y.; Chen, Y.Q.; Luo, X.Q.; Zhang, H.; Huang, L. Bin MiR-124 Contributes to Glucocorticoid Resistance in Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia by Promoting Proliferation, Inhibiting Apoptosis and Targeting the Glucocorticoid Receptor. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2017, 172, 62–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Zhang, X.; Wei, W.; Liu, X.; Tian, Y.; Han, H.; Zhang, L.; Wu, W.; Chen, J. Myostatin/Smad4 Signaling-Mediated Regulation of Mir-124-3p Represses Glucocorticoid Receptor Expression and Inhibits Adipocyte Differentiation. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2019, 316, E635–E645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, B.; Dunbar, M.; Shelton, R.C.; Dwivedi, Y. Identification of MicroRNA-124-3p as a Putative Epigenetic Signature of Major Depressive Disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology 2017, 42, 864–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Che, X.; Yang, N.; Bai, Z.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, L.; Pei, H. MiR-135b-5p Promotes Migration, Invasion and EMT of Pancreatic Cancer Cells by Targeting NR3C2. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2017, 96, 1341–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ouyang, Y. Elevated MicroRNA-135b-5p Relieves Neuronal Injury and Inflammation in Post-Stroke Cognitive Impairment by Targeting NR3C2. Int. J. Neurosci. 2021, 132, 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozomara, A.; Birgaoanu, M.; Griffiths-Jones, S. MiRBase: From MicroRNA Sequences to Function. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D155–D162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGeary, S.E.; Lin, K.S.; Shi, C.Y.; Pham, T.M.; Bisaria, N.; Kelley, G.M.; Bartel, D.P. The Biochemical Basis of MicroRNA Targeting Efficacy. Science 2019, 366, eaav1741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasuki, L.; Antunes, X.; Coelho, M.C.A.; Lamback, E.B.; Galvão, S.; Silva Camacho, A.H.; Chimelli, L.; Ventura, N.; Gadelha, M.R. Accuracy of Microcystic Aspect on T2-Weighted MRI for the Diagnosis of Silent Corticotroph Adenomas. Clin. Endocrinol. 2020, 92, 145–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thodou, E.; Argyrakos, T.; Kontogeorgos, G. Galectin-3 as a Marker Distinguishing Functioning from Silent Corticotroph Adenomas. Hormones 2007, 6, 227–232. [Google Scholar]

- Valassi, E.; Santos, A.; Yaneva, M.; Tóth, M.; Strasburger, C.J.; Chanson, P.; Wass, J.A.H.; Chabre, O.; Pfeifer, M.; Feelders, R.A.; et al. The European Registry on Cushing’s Syndrome: 2-Year Experience. Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2011, 165, 383–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langlois, F.; Shao, D.; Lim, T.; Yedinak, C.G.; Cetas, I.; Mccartney, S.; Cetas, J.; Dogan, A.; Fleseriu, M. Predictors of Silent Corticotroph Adenoma Recurrence; a Large Retrospective Single Center Study and Systematic Literature Review. Pituitary 2018, 21, 32–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahangiri, A.; Wagner, J.R.; Pekmezci, M.; Hiniker, A.; Chang, E.F.; Kunwar, S.; Blevins, L.; Aghi, M.K. A Comprehensive Long-Term Retrospective Analysis of Silent Corticotrophic Adenomas vs Hormone-Negative Adenomas. Neurosurgery 2013, 73, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strickland, B.A.; Shahrestani, S.; Briggs, R.G.; Jackanich, A.; Tavakol, S.; Hurth, K.; Shiroishi, M.S.; Liu, C.-S.J.; Carmichael, J.D.; Weiss, M.; et al. Silent Corticotroph Pituitary Adenomas: Clinical Characteristics, Long-Term Outcomes, and Management of Disease Recurrence. J. Neurosurg. 2021, 135, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machado, M.C.; Alcantara, A.E.E.; Pereira, A.C.L.; Cescato, V.A.S.; Castro Musolino, N.R.; de Mendonça, B.B.; Bronstein, M.D.; Fragoso, M.C.B.V. Negative Correlation between Tumour Size and Cortisol/ ACTH Ratios in Patients with Cushing’s Disease Harbouring Microadenomas or Macroadenomas. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 2016, 39, 1401–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- García-Martínez, A.; Fuentes-Fayos, A.C.; Fajardo, C.; Lamas, C.; Cámara, R.; López-Muñoz, B.; Aranda, I.; Luque, R.M.; Picó, A. Differential Expression of MicroRNAs in Silent and Functioning Corticotroph Tumors. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, H.Y.; Lin, Y.C.D.; Li, J.; Huang, K.Y.; Shrestha, S.; Hong, H.C.; Tang, Y.; Chen, Y.G.; Jin, C.N.; Yu, Y.; et al. MiRTarBase 2020: Updates to the Experimentally Validated MicroRNA-Target Interaction Database. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, D148–D154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koning, A.S.C.A.M.; Buurstede, J.C.; van Weert, L.T.C.M.; Meijer, O.C. Glucocorticoid and Mineralocorticoid Receptors in the Brain: A Transcriptional Perspective. J. Endocr. Soc. 2019, 3, 1917–1930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakai, Y.; Usui, T.; Tsukada, T.; Takahashi, H.; Fukata, J.; Fukushima, M.; Senoo, K.; Imura, H. Molecular Mechanisms of Glucocorticoid Inhibition of Human Proopiomelanocortin Gene Transcription. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1991, 40, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drouin, J.; Charron, J.; Gagner, J.-P.; Jeannotte, L.; Nemer, M.; Plante, R.K.; Wrange, Ö. Pro-opiomelanocortin Gene: A Model for Negative Regulation of Transcription by Glucocorticoids. J. Cell. Biochem. 1987, 35, 293–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huizenga, N.A.T.M.; De Lange, P.; Koper, J.W.; Clayton, R.N.; Farrell, W.E.; Van Der Lely, A.J.; Brinkmann, A.O.; De Jong, F.H.; Lamberts, S.W.J. Human Adrenocorticotropin-Secreting Pituitary Adenomas Show Frequent Loss of Heterozygosity at the Glucocorticoid Receptor Gene Locus. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1998, 83, 917–921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, H.; Liu, Y.; Lu, L.; Gong, F.; Wang, L.; Duan, L.; Yao, Y.; Wang, R.; Chen, S.; Mao, X.; et al. Effect of 3 NR3C1 Mutations in the Pathogenesis of Pituitary ACTH Adenoma. Endocrinology 2021, 162, bqab167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Y.M.; Takayanagi, R.; Imasaki, K.; Ohe, K.; Ikuyama, S.; Yanase, T.; Nawata, H. Low Level of Glucocorticoid Receptor Messenger Ribonucleic Acid in Pituitary Adenomas Manifesting Cushing’s Disease with Resistance to a High Dose-Dexamethasone Suppression Test. Clin. Endocrinol. 1998, 49, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ebisawa, T.; Tojo, K.; Tajima, N.; Kamio, M.; Oki, Y.; Ono, K.; Sasano, H. Immunohistochemical Analysis of 11-β-Hydroxysteroid Dehydrogenase Type 2 and Glucocorticoid Receptor in Subclinical Cushing’s Disease Due to Pituitary Macroadenoma. Endocr. Pathol. 2008, 19, 252–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledderose, C.; Möhnle, P.; Limbeck, E.; Schütz, S.; Weis, F.; Rink, J.; Briegel, J.; Kreth, S. Corticosteroid Resistance in Sepsis Is Influenced by MicroRNA-124-Induced Downregulation of Glucocorticoid Receptor-α. Crit. Care Med. 2012, 40, 2745–2753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spencer, R.L.; Deak, T. A Users Guide to HPA Axis Research. Physiol. Behav. 2017, 178, 43–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, F.; Ozawa, H.; Matsuda, K.I.; Nishi, M.; Kawata, M. Colocalization of Mineralocorticoid Receptor and Glucocorticoid Receptor in the Hippocampus and Hypothalamus. Neurosci. Res. 2005, 51, 371–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castinetti, F.; Fassnacht, M.; Johanssen, S.; Terzolo, M.; Bouchard, P.; Chanson, P.; Cao, D.; Morange, I.; Picó, A.; Ouzounian, S.; et al. Merits and Pitfalls of Mifepristone in Cushing’s Syndrome. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2009, 160, 1003–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fleseriu, M.; Laws, E.R.; Witek, P.; Pivonello, R.; Ferrigno, R.; de Martino, M.C.; Simeoli, C.; di Paola, N.; Pivonello, C.; Barba, L.; et al. Medical Treatment of Cushing’s Disease: An Overview of the Current and Recent Clinical Trials. Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senyuk, V.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Ming, M.; Premanand, K.; Zhou, L.; Chen, P.; Chen, J.; Rowley, J.D.; Nucifora, G.; et al. Critical Role of MiR-9 in Myelopoiesis and EVI1-Induced Leukemogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2013, 110, 5594–5599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.Z.; Chang, B.; Li, X.D.; Zhang, Q.H.; Zou, Y.H. MicroRNA-9 Promotes the Proliferation, Migration, and Invasion of Breast Cancer Cells via down-Regulating FOXO1. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 2017, 19, 1133–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guttilla, I.K.; White, B.A. Coordinate Regulation of FOXO1 by MiR-27a, MiR-96, and MiR-182 in Breast Cancer Cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhao, S.; Cui, M.; Wang, Q. Down-Regulation of MicroRNA-135b Inhibited Growth of Cervical Cancer Cells by Targeting FOXO1. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 2015, 8, 10294–10304. [Google Scholar]

- Lau, P.; Bossers, K.; Janky, R.; Salta, E.; Frigerio, C.S.; Barbash, S.; Rothman, R.; Sierksma, A.S.R.; Thathiah, A.; Greenberg, D.; et al. Alteration of the MicroRNA Network during the Progression of Alzheimer’s Disease. EMBO Mol. Med. 2013, 5, 1613–1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapali, J.; Kabat, B.E.; Schmidt, K.L.; Stallings, C.E.; Tippy, M.; Jung, D.O.; Edwards, B.S.; Nantie, L.B.; Raeztman, L.T.; Navratil, A.M.; et al. Foxo1 Is Required for Normal Somatotrope Differentiation. Endocrinology 2016, 157, 4351–4363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garrel, G.; Denoyelle, C.; L’Hôte, D.; Picard, J.Y.; Teixeira, J.; Kaiser, U.B.; Laverrière, J.N.; Cohen-Tannoudji, J. GnRH Transactivates Human AMH Receptor Gene via Egr1 and FOXO1 in Gonadotrope Cells. Neuroendocrinology 2019, 108, 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skarra, D.V.; Arriola, D.J.; Benson, C.A.; Thackray, V.G. Forkhead Box O1 Is a Repressor of Basal and GnRH-Induced Fshb Transcription in Gonadotropes. Mol. Endocrinol. 2013, 27, 1825–1839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiao, Z.; Wang, Z.; Hu, B.; Mao, Z.; Zhu, D.; Feng, Y.; Zhu, Y. MiR-1299 Promotes the Synthesis and Secretion of Prolactin by Inhibiting FOXO1 Expression in Drug-Resistant Prolactinomas. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2019, 520, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benite-Ribeiro, S.A.; de Lima Rodrigues, V.A.; Machado, M.R.F. Food Intake in Early Life and Epigenetic Modifications of Pro-Opiomelanocortin Expression in Arcuate Nucleus. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2021, 48, 3773–3784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knosp, E.; Steiner, E.; Kitz, K.; Matula, C.; Parent, A.D.; Laws, E.R.; Ciric, I. Pituitary Adenomas with Invasion of the Cavernous Sinus Space: A Magnetic Resonance Imaging Classification Compared with Surgical Findings. Neurosurgery 1993, 33, 610–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bujko, M.; Kober, P.; Boresowicz, J.; Rusetska, N.; Zeber-Lubecka, N.; Paziewska, A.; Pekul, M.; Zielinski, G.; Styk, A.; Kunicki, J.; et al. Differential MicroRNA Expression in USP8-Mutated and Wild-Type Corticotroph Pituitary Tumors Reflect the Difference in Protein Ubiquitination Processes. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mi, H.; Ebert, D.; Muruganujan, A.; Mills, C.; Albou, L.P.; Mushayamaha, T.; Thomas, P.D. PANTHER Version 16: A Revised Family Classification, Tree-Based Classification Tool, Enhancer Regions and Extensive API. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, D394–D403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

|

Filed under: Cushing's, pituitary, Rare Diseases | Tagged: Corticotroph pituitary adenoma, Cushing's Disease, miRNA, pituitary | Leave a comment »

View Full Size

View Full Size