Introduction

Chronic persistent hypercortisolism is a life-threatening condition that requires effective treatment. Untreated exposure to excessive cortisol secretion leads to severely increased morbidity and mortality due to cardiovascular diseases, thromboembolic events, sepsis, visceral obesity, impairment of glucose metabolism, and dyslipidaea, as well as musculoskeletal disorders, such as myopathy, osteoporosis, and skeletal fractures. Moreover, neuropsychiatric disorders, such as impairment of cognitive function, depression, or mania, as well as impairment of reproductive function can frequently occur.1,2 Cushing’s disease (CD) – a disorder caused by a pituitary adenoma secreting adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) – is the most common cause of hypercortisolism. Cushing’s syndrome (CS) includes all other causes of cortisol excess, including ectopic ACTH production as well as direct cortisol overproduction by adrenal adenoma (cortisol-producing adenoma [CPA]) or adrenocortical carcinoma (ACC). Approximately 10% of hypercortisolism cases result from CPA. The first line therapy is a surgical resection of the tumor, which is the source of hormone excess. However, in many patients surgery is not fully efficient and other therapies are required to reduce cortisol levels. Additionally, due to severe cardiovascular complications and unstable DM, the surgical approach sometimes entails unacceptable risk and it is frequently postponed until cortisol levels are lowered. Pharmacotherapy with steroidogenesis inhibitors reduces cortisol levels and improves the symptoms of hypercortisolism.1,2 As CD is the most common cause of cortisol excess, most studies have focused on the efficacy and safety of novel steroidogenesis inhibitors, including patients with CD only.3–6 This is exactly the case with osilodrostat – a new potent inhibitor of 11β-hydroxylase.3–6 More data are available for metyrapone efficacy and safety in CSA,7 as the drug has been available much longer than osilodrostat. A study by Detomas et al, which reported results of comparison of efficacy of metyrapone and osilodrostat, included 4 patients with adrenal CS, among whom one CPA patient was treated with osilodrostat.8 Osilodrostat is approved in the United States to treat CD in patients in whom pituitary surgery was not curative or is contraindicated.9 In Poland, osilodrostat therapy is available for patients with all kinds of endogenous hypercortisolism not curative with other approaches, within a national program of emergency access to drug technologies.10 Reports on osilodrostat application in CPA are highly valuable as data on potential differences in the treatment regimens between CD and CPA are scarce.

Here, we present two patients with CPA in whom the response and doses of osilodrostat were different from those reported in patients with CD. The main purpose of this study was to demonstrate that the efficacy of osilodrostat in CPA is high, although initial resistance to treatment or even deterioration of hypercortisolism can occur during the application of lower doses of the drug.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Patients

We retrospectively analyzed medical files of two consecutive patients with CPA treated with osilodrostat. The analysis included medical history, laboratory and imaging results as well as a detailed reports of adverse events.

Laboratory and Imaging Procedures

Serum cortisol and ACTH levels were measured by electrochemiluminescence immunoassay (ECLIA) using a Cobas e601 analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA). UFC excretion was measured by chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay (CMIA) using an Abbott Architect ci4100 analyzer (Abbott, Abbott Park, IL, USA). Cross-reactivity with 11-deoxycortisol for this method is very low (2.1% according to the manufacturer’s data). Potassium levels were measured by ion-selective electrode potentiometry using a Beckman Coulter DxC 700 AU Chemistry Analyzer (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA, USA). Computed tomography (CT) imaging was performed using a Philips Ingenuity Core 128 system (Philips, the Netherlands).

Ethics Procedures

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written informed consent was obtained from the patients for publication of this paper. The approval of Institutional Ethics Committee was obtained to publish the case details (approval code KB 33/2023).

Presentation of the Cases

Case 1

A 51-year-old female was referred to our department in November 2021 because of CPA, disqualified from surgery because of severe hypertension with a poor response to antihypertensive therapy and uncontrolled DM despite high doses of insulin. Additionally, the patient presented with hyperlipidemia and severe obesity (BMI=50.7 kg/m2), gastritis, depression, and osteoarthritis. On admission, she complained of a tendency to gain weight, fragile skin that bruised easily, difficulty with wound healing, susceptibility to infections, and insomnia. Physical examination revealed a moon face with plethora, a buffalo hump, central obesity with proximal muscle atrophy, and purple abdominal striae.

The CPA diagnosis was initially made two years earlier, but the patient did not qualify for surgery due to a hypertensive crisis. Soon after this episode, the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic began, and the patient was afraid of visiting any medical center because her son had died of COVID-19. Therefore, she was referred to our center for life-threatening hypercortisolism two years later.

At the time of admission, computed tomography (CT) imaging revealed a right adrenal tumor of 34x24x37mm, with a basal density of 21 HU and a contrast washout rate typical for adenomas (83%). The size and CT characteristics were identical as they were two years earlier. High serum cortisol levels, undetectable ACTH concentrations, and a lack of physiological diurnal rhythm of cortisol secretion were observed (Table 1). Urinary free cortisol (UFC) excretion was 310 µg/24 h, with an upper normal limit (UNL) of 176 µg/24 h. No cortisol suppression was achieved in high-dose dexamethasone suppression test (DST) (Table 1). Other adrenal-related hormonal parameters were within normal ranges, with values as follows: DHEA-S 42.68 µg/dl, aldosterone 3.24 ng/mL, and renin 59.14 µIU/mL.

|

Table 1 Laboratory Results Before Osilodrostat Therapy – Case 1 |

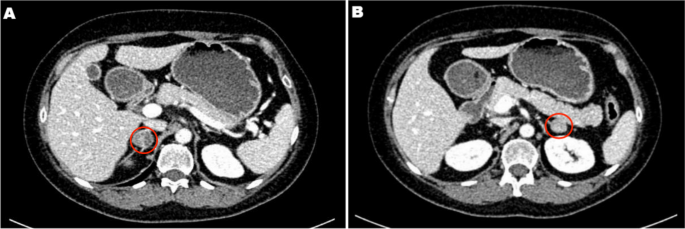

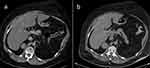

Due to multiple severe systemic complications, including uncontrolled hypertension, decompensated DM, and cardiac insufficiency, treatment with osilodrostat was introduced for life-saving pre-surgical management. Osilodrostat was started at a dose of 1 mg twice daily and gradually increased to 6 mg per day with actually an inverse response of serum cortisol level. The late-night cortisol level increased from 16 µg/dl to 25 µg/dl. As the full effect of the osilodrostat dose can occur even after a few weeks, the patient was discharged from hospital and instructed to contact her attending doctor immediately if any health deterioration was noticed. In the case of improvement in the patient’s condition, the next hospitalization was planned 3 weeks later. After three weeks of no contact with the patient, she was readmitted to our department with life-threatening escalation of hypercortisolism, severe hypokalemia, and further deterioration of hypertension, DM, cardiac insufficiency, dyspnea, and significant edemas, including facial edema. Treatments of hypertension, cardiac insufficiency, and DM were intensified, as presented in Table 2. Despite active potassium supplementation, life-threatening hypokalemia of 2.1 mmol/l occurred. Previously observed depression was exaggerated with severe anxiety and fear of death. The dose of osilodrostat was increased to 8 mg/day, and after three days of treatment a further elevation of serum cortisol was found, with an increase in UFC up to 9 × UNL (1546.2 µg/24 h). Due to an entirely unexpected inverse cortisol response, CT imaging was performed and revealed progression of the adenoma size to 39 × 36 × 40 mm, with a slight increase in density up to 27 HU as compared to the previous CT scan performed a month earlier (Figure 1).

|

Table 2 Changes in the Most Important Parameters During Osilodrostat Therapy – Case 1 |

|

Figure 1 Progression of the adrenal adenoma size during the initial doses of osilodrostat: (a) CT scan directly before osilodrostat therapy – solid nodule 34x24x37 mm, basal density 21 HU; (b) CT scan during treatment with 8 mg of osilodrostat daily – solid nodule 39x36x40 mm, basal density of 27 HU. |

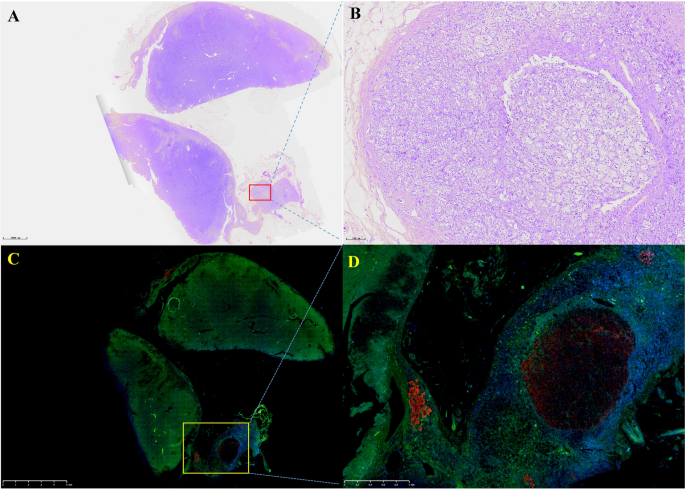

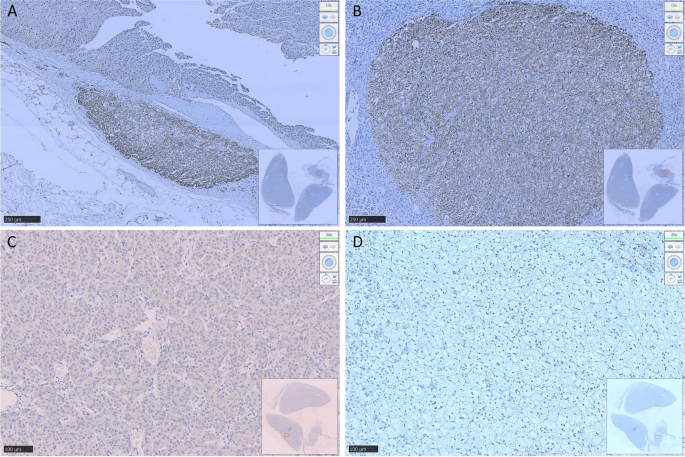

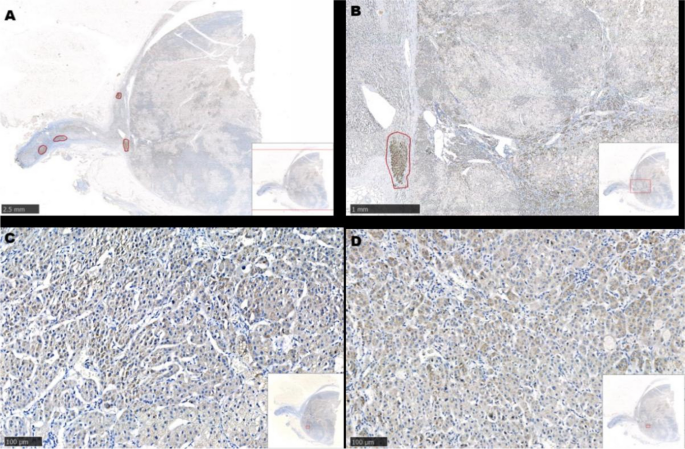

Considering the extremely high risk associated with such a rapid cortisol increase and related complications, decision of fast osilodrostat dose escalation was made. The dose was increased by 5 mg every other day, up to 45 mg per day, and, finally, a gradual decrease in the cortisol level (Table 2) was achieved, with UFC normalization to 168 µg/24 h. During dose escalation, no deterioration in the adverse effects (AEs) of osilodrostat was observed. Conversely, hypokalemia gradually improved despite a simultaneous reduction in potassium supplementation (Table 2). Facial edema decreased and the level of anxiety improved significantly. The course of hypertension severity as well as a summary of the main parameters controlled during treatment and the medications used are presented in Table 2. As soon as the cortisol level normalized, the patient was referred for surgery and underwent right adrenalectomy without any complications. Histopathology results confirmed a benign adenoma of the right adrenal gland (encapsulated, well-circumscribed tumor consisting of lipid-rich cells with small and uniform nuclei, mostly with eosinophilic intracytoplasmic inclusions). After surgery, hydrocortisone replacement therapy was administered. A few days after surgery, blood pressure and glucose levels gradually decreased, and the patient required reduction of antihypertensive and antidiabetic medications. After 22 months of follow-up, the patient’s general condition is good with no signs of recurrence. Antidepressant treatment is no longer required in this patient. Body mass index was significantly reduced to 40 kg/m2. The antihypertensive medication was completely discontinued, and the glucose level is controlled only with metformin. The patient still requires hydrocortisone substitution at a dose of 30 mg/day.

Case 2

A 39-year-old female was referred to our department in November 2022 with a diagnosis of CPA and unstable hypertension, for which surgery was contraindicated. The patient was unsuccessfully treated with triple antihypertensive therapy (telmisartan 40 mg/day, nebivolol 5 mg/day, and lercanidipine 20 mg/day). The patient reported weight gain, muscle weakness, acne, fragile skin that bruised easily, and secondary amenorrhea. Other comorbidities included gastritis, hypercholesterolemia, and osteoporosis. Physical examination revealed typical signs of Cushing’s syndrome, such as abnormal fat distribution, particularly in the abdomen and supraclavicular fossae, proximal muscle atrophy, moon face, and multiple hematomas. A lack of a serum cortisol diurnal rhythm with high late-night serum cortisol and undetectable ACTH levels was found (Table 3). The short DST revealed no cortisol suppression (Table 3), and the UFC result was 725 µg/24 h, which exceeded the UNL more than four times. The serum levels of renin, aldosterone, and 24-h urine fractionated metanephrines were within the normal ranges. Computed tomography imaging revealed a left adrenal gland tumor measuring 25 × 26 × 22 mm, with a basal density of 32 HU and a washout rate typical for adenoma (76%).

|

Table 3 Laboratory Results Before Osilodrostat Therapy – Case 2 |

Osilodrostat therapy was administered for preoperative management. The initial daily dose was 2 mg/day, increased gradually by 2 mg every day with no serum cortisol response (late night cortisol levels 15.8–18.5 µg/dl) and no AEs of the drug (Table 4). After the daily dose of osilodrostat reached 10 mg, it was escalated by 5 mg every other day, initially with no serum cortisol reduction. The dose was increased to 45 mg daily (with the lowest detected late-night serum cortisol of 9.6 µg/dl) (Table 4).

|

Table 4 Changes in the Most Important Parameters During Osilodrostat Therapy – Case 2 |

After a week of administration of 45 mg daily, UFC normalization was achieved. Despite rapid dose escalation, no AEs were observed during the entire therapy period. Potassium levels were normal without any supplementation (the lowest detected serum potassium level was 3.9 mmol/l; all other results were over 4.0 mmol/l) (Table 4). After UFC normalization, left adrenalectomy was performed without complications. Histopathological examination revealed benign adrenal adenoma. Antihypertensive therapy was reduced only to 2.5 mg of nebivolol daily. The patient’s general condition improved significantly. Currently, hydrocortisone replacement therapy is administered at a dose of 15 mg/day.

Discussion

Osilodrostat is a novel potent steroidogenesis inhibitor whose efficacy and safety have been thoroughly analyzed in clinical trials of patients with CD, the most common cause of endogenous hypercortisolism. No clinical trial of osilodrostat therapy in CPA has been performed, as this disease constitutes only 10% of all cases of endogenous hypercortisolism. Moreover, osilodrostat is not approved by the FDA for hypercortisolism conditions other than CD.9 Therefore, data on potential differences in the treatment regimen are lacking.

During the course of already reported trials in CD, osilodrostat doses were escalated slowly, every 2–3 weeks,3,5,6 with an excellent response to quite low doses of the drug.3–6 In the LINC 2 extension study the median average dose was 10.6 mg/day,5 while in the LINC 3 extension study and the LINC 4 study it was 7.4 mg/day and 6.9 mg/day, respectively.4,6 In most cases, a significant decrease of hypercortisolism was reported with the low doses of osilodrostat (4 or 10 mg/day). Moreover, some patients received 1 mg/day or even 1 mg every other day, with a good response.6 Even in rare cases of CD in whom initial short-term etomidate therapy was given at the beginning of osilodrostat therapy, due to highly severe life-threatening symptoms of hypercortisolism, the final effective dose of osilodrostat was much lower than that in our patients with CPA (25 mg/day vs 45 mg/day) and no increase of cortisol level was observed.11

It should be underlined that many cases of adrenal insufficiency during osilodrostat therapy in patients with CD have been reported,3–6,12,13 and – therefore – low initial dose with slow gradual dose escalation is recommended in patients with CD.1,6,13

In the cases presented here, CPA led to severe hypercortisolism, the complications of which constituted contraindications for surgery. Therefore, osilodrostat therapy was introduced as a presurgical treatment. In Case 1, the therapy was started at low doses according to the approved product characteristics.14 Due to the severity of hypertension, which was uncontrolled despite of active antihypertensive therapy, as well as to unstable DM, the doses were increased faster than recommended. Surprisingly, we immediately observed a gradual increase in hypercortisolism, in both serum cortisol levels and the UFC, with simultaneous burst of complications related to both hypercortisolism itself and 11β-hydroxylase inhibition. Life-threatening episodes of hypertensive crisis responded poorly to standard therapies. Severe exaggeration of cardiac insufficiency could probably be related to these episodes as well as to deep hypokalemia, which occurred despite potassium supplementation. Hypokalemia is a typical complication of treatment with 11β-hydroxylase inhibitors due to the accumulation of adrenal hormone precursors. However, Patient 1 required much higher doses of potassium supplementation, both parenteral and oral, than ever described during osilodrostat therapy.3–6,13 The dose of 20 mg/day of osilodrostat was the first one which led to noticeable cortisol reduction and a decrease in systolic blood pressure (SBP) to below 170 mmHg. Surprisingly, instead of the expected deterioration of hypokalemia, parenteral potassium administration could be stopped with an osilodrostat dose of 20 mg/day and oral supplementation was gradually reduced simultaneously with osilodrostat dose escalation. The reason why such severe hypokalemia occurred with low doses of osilodrostat and did not deteriorate further seems complex. One possible reason is the administration of high doses of potassium-saving antihypertensive drugs such as spironolactone and the angiotensin II receptor antagonist telmisartan. Additionally, one can consider other possible mechanisms, such as downregulation of the receptors of deoxycorticosterone (DOC) or other adrenal hormone precursors. However, this hypothesis requires further research and confirmation. Such an improvement of the potassium level during osilodrostat dose escalation was previously demonstrated in a patient with CD.11 Interestingly, in our Patient 2, no potassium supplementation was required during the whole time of osilodrostat therapy, although the doses were increased intensively up to the finally effective dose, which was the same (45 mg/day) as for Patient 1. In Patient 2, no actual response to doses lower than 20 mg/day was observed. UFC normalization was achieved after a week of administration of 45 mg/day, five weeks from the beginning of therapy. Although UFC normalization is not always required in pre-surgical treatment, clinical symptoms significantly improved in our patients only after the UFC upper normal level was achieved.

The present paper is one of only a few reports focused on osilodrostat therapy in CPA, and the only one presenting a different therapy course as compared to patients with CD. No case of CPA resistance to low doses of osilodrostat has been described. It should be underlined that in our report “low doses” of osilodrostat were higher than the average mean doses of osilodrostat used in clinical trials in patients with CD.3–6 Therefore, they should not generally be considered low but only much lower than those which were effective in our patients. Malik and Ben-Shlomo presented a case of CPA treated with osilodrostat, with an immediate decrease in cortisol level at 4 mg/day and adrenal insufficiency symptoms after dose escalation to 8 mg/day.15 Similar to our two cases, their patient was a middle-aged female with normal results of all other adrenal parameters, such as renin, angiotensin, or metanephrine levels. However, a CT scan was not performed (or presented), while magnetic resonance imaging revealed an indeterminate adrenal gland mass without a typical contrast phase/out-of-phase dropout for adenoma.15 Therefore, different morphology of cortisol-secreting adrenal tumor can potentially be considered a reason of the different response to treatment. Tanaka et al performed a multicenter study on the efficacy and safety of osilodrostat in Japanese patients with non-CD Cushing’s syndrome.16 Five patients with CPA were included in the study, and none of them required osilodrostat doses higher than 10 mg/day to achieve UFC normalization. However, most of the patients presented by Tanaka et al were previously treated with metyrapone,16 whereas both of our patients were treatment-naive. Previous metyrapone therapy may be considered as a potential reason of better response to osilodrostat. This hypothesis was confirmed in the quoted study by Tanaka et al, who demonstrated that at week 12 the median percent changes in the mUFC values were higher in patients previously treated with metyrapone (–98.97%) than in treatment-naive cases (–86.65%).16 Detomas et al performed a comparison of efficacy and safety of osilodrostat and metyrapone, with one CPA patients included in a group treated with osilodrostat, however no data on a dose required for a disease control are available separately for this particular patient.8 To the best of our knowledge, no more CPA cases have been described and therefore no further comparison is available.

Higher doses of osilodrostat were administered to a group of seven patients with hypercortisolism due to adrenocortical carcinoma (ACC) presented by Tabarin et al.17 A full control of hypercortisolism was achieved in one patient for each dose of 4, 8, 10, and 20 mg/day, and in three patients treated with 40 mg/day.17 These patients, however received other therapies including mitotane and chemotherapy, which can significantly modify the response to osilodrostat.

Several authors have reported the phenomenon of a partial or total loss of response to osilodrostat.5,16,17 In such cases, a response to treatment was initially achieved and then lost during treatment with the same dose. A further increase in osilodrostat dose usually resulted in the response resumption.5,16,17 Such a situation could not be suspected in either of our cases.

The presented cases provide a novel insight into modalities of treatment with osilodrostat in patients with CPA and demonstrate for the first time that an inverse cortisol response is possible in CPA cases, especially those with a higher CT density of adrenal adenoma. Such a situation should not be considered a contraindication to dose escalation. Conversely, the dose should be increased more intensively so as to achieve the initial efficacy threshold, which was 20 mg/day in both of our patients. The fully efficient dose that allowed UFC normalization was more than twice as high (45 mg/day in both cases). A similar approach should be applied in patients who do not respond to lower doses, such as Patient 2. The safety of osilodrostat therapy is strictly individual and not dose dependent in patients with CPA. Adverse events, including hypokalemia, severe hypertension, and edema, can be of life-threatening severity or may not occur regardless of the dose. Moreover, AEs of high severity may decrease with osilodrostat dose escalation. Our study demonstrated that osilodrostat is efficient and can be used in patients with CPA as a pre-surgical therapy if surgery is contraindicated due to hypercortisolism complications.

Our study presented two cases of CPA treated with osilodrostat, and a small size of our group is the main limitation of this report. Future research is required to confirm our observations.

Conclusion

In some patients with CPA, the doses of osilodrostat required for disease control can be much higher than those previously reported. Acceleration of the dose increase can be fast, and the risk of overdosing, adrenal insufficiency, and later necessity of dose reduction seem to be much lower than it could be expected. Low initial doses (<20 mg/day in our study) can be entirely ineffective or can even cause exacerbation of hypercortisolism, whereas high doses (45 mg/day in the present study) are efficient in pre-surgery UFC normalization. AEs associated with osilodrostat can be rapid, with severe hypokalemia despite active potassium supplementation, or may not occur even if high doses of osilodrostat are applied. Therefore, close monitoring for potential AEs is necessary.

Acknowledgments

The abstract included some parts of this paper was presented at the European Congress of Endocrinology ECE2023 as a rapid communication. The abstract was published in the Endocrine Abstracts Vol. 90 [https://www.endocrine-abstracts.org/ea/0090/].

Funding

The publication of this report was financially supported by the statutory funds of the Polish Mother’s Memorial Hospital – Research Institute, Lodz, Poland.

Disclosure

Professor Przemysław Witek reports personal fees from Investigator in the clinical trials paid by Novartis and Recordati Rare Diseases, outside the submitted work; lectures fees from Recordati Rare Diseases, Strongbridge, IPSEN. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Fleseriu M, Auchus R, Bancos I, et al. Consensus on diagnosis and management of Cushing’s disease: a guideline update. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021;9(12):847–875. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(21)00235-7

2. Pivonello R, Isidori AM, De Martino MC, et al. Complications of Cushing’s syndrome: state of the art. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016;4(7):611–629. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(16)00086-3

3. Pivonello R, Fleseriu M, Newell-Price J, et al. Efficacy and safety of osilodrostat in patients with Cushing’s disease (LINC 3): a multicentre Phase III study with a double-blind, randomised withdrawal phase. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2020;8(9):48–761. doi:10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30240-0

4. Fleseriu M, Newell-Price J, Pivonello R, et al. Long-term outcomes of osilodrostat in Cushing’s disease: LINC 3 study extension. Eur J Endocrinol. 2022;187(4):531–541. doi:10.1530/EJE-22-0317

5. Fleseriu M, Biller BMK, Bertherat J, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of osilodrostat in Cushing’s disease: final results from a Phase II study with an optional extension phase (LINC 2). Pituitary. 2022;25(6):959–970. doi:10.1007/s11102-022-01280-6

6. Gadelha M, Bex M, Feelders RA, et al. Randomized trial of osilodrostat for the treatment of Cushing disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022;107(7):e2882–e2895. doi:10.1210/clinem/dgac178

7. Daniel E, Aylwin S, Mustafa O, et al. Effectiveness of metyrapone in treating cushing’s syndrome: a retrospective multicenter study in 195 patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(11):4146–4154. doi:10.1210/jc.2015-2616

8. Detomas M, Altieri B, Deutschbein T, et al. Metyrapone versus osilodrostat in the short-term therapy of endogenous cushing’s syndrome: results from a single center cohort study. Front Endocrinol. 2022;13:903545. doi:10.3389/fendo.2022.903545

9. U.S. food and drug administration home page. Available from: https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-approves-new-treatment-adults-cushings-disease. Accessed March 22, 2023.

10. Agency for health technology assessment and tariff system home page. Available from: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwj6ypGbsfT9AhUMzYsKHTgAD2EQFnoECA8QAQ&url=https%3A%2F%2Fbipold.aotm.gov.pl%2Fassets%2Ffiles%2Fwykaz_tli%2FRAPORTY%2F2020_010.pdf&usg=AOvVaw3P2Q85gwi3JcxKkW3uxfOb. Accessed March 22, 2022.

11. Dzialach L, Sobolewska J, Respondek W, et al. Cushing’s syndrome: a combined treatment with etomidate and osilodrostat in severe life-threatening hypercortisolemia. Hormones. 2022;21(4):735–742. doi:10.1007/s42000-022-00397-4

12. Ekladios C, Khoury J, Mehr S, et al. Osilodrostat-induced adrenal insufficiency in a patient with Cushing’s disease. Clin Case Rep. 2022;10(11):e6607. doi:10.1002/ccr3.6607

13. Fleseriu M, Biller BMK. Treatment of Cushing’s syndrome with osilodrostat: practical applications of recent studies with case examples. Pituitary. 2022;25(6):795–809. doi:10.1007/s11102-022-01268-2

14. Summary of product characteristics. Available from: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&ved=2ahUKEwim1_KdsvT9AhVq-ioKHUZKAc4QFnoECA4QAQ&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.ema.europa.eu%2Fen%2Fdocuments%2Fproduct-information%2Fisturisa-epar-product-information_pl.pdf&usg=AOvVaw0S8nayCTdqNh1LsEcXVLEu. Accessed March 24, 2023.

15. Malik RB, Ben-Shlomo A. Adrenal cushing’s syndrome treated with preoperative osilodrostat and adrenalectomy. AACE Clin Case Rep. 2022;8(6):267–270. doi:10.1016/j.aace.2022.10.001

16. Tanaka T, Satoh F, Ujihara M, et al. A multicenter, Phase 2 study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of osilodrostat, a new 11β-hydroxylase inhibitor, in Japanese patients with endogenous Cushing’s syndrome other than Cushing’s disease. Endocr J. 2020;67(8):841–852. doi:10.1507/endocrj.EJ19-0617

17. Tabarin A, Haissaguerre M, Lassole H, et al. Efficacy and tolerance of osilodrostat in patients with Cushing’s syndrome due to adrenocortical carcinomas. Eur J Endocrinol. 2022;186(2):K1–K4. doi:10.1530/EJE-21-1008

© 2024 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at

© 2024 The Author(s). This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at