Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

2.4. Additional Hormone Tests

2.5. Laboratory Tests

2.6. Anamnesis and Physical Examination

2.7. Echocardiography

2.8. Impedance Cardiography

2.9. Applanation Tonometry

2.10. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Baseline Characteristics

3.2. Echocardiographic Assessment

3.3. ICG and AT Assessment

3.4. Correlation Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Clinical Implications

4.2. Limitations

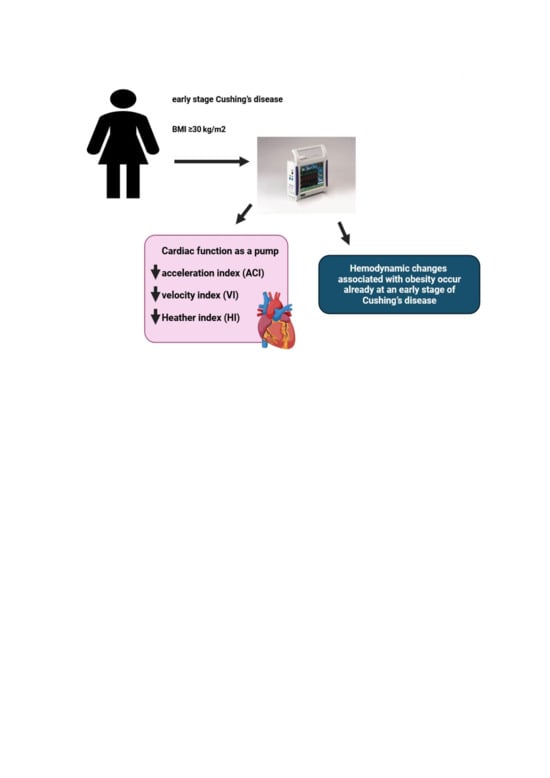

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pivonello, R.; Isidori, A.M.; De Martino, M.C.; Newell-Price, J.; Biller, B.M.; Colao, A. Complications of Cushing’s syndrome: State of the art. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016, 4, 611–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekkers, O.M.; Horváth-Puhó, E.; Jørgensen, J.O.; Cannegieter, S.C.; Ehrenstein, V.; Vandenbroucke, J.P.; Pereira, A.M.; Sørensen, H.T. Multisystem morbidity and mortality in Cushing’s syndrome: A cohort study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 98, 2277–2284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pivonello, R.; Faggiano, A.; Lombardi, G.; Colao, A. The metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular risk in Cushing’s syndrome. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. N. Am. 2005, 34, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pivonello, R.; De Leo, M.; Vitale, P.; Cozzolino, A.; Simeoli, C.; De Martino, M.C.; Lombardi, G.; Colao, A. Pathophysiology of diabetes mellitus in Cushing’s syndrome. Neuroendocrinology 2010, 1, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davy, K.P.; Hall, J.E. Obesity and hypertension: Two epidemics or one? Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2004, 286, R803–R813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.J.; Pramyothin, P.; Karastergiou, K.; Fried, S.K. Deconstructing the roles of glucocorticoids in adipose tissue biology and the development of central obesity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1842, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mancini, T.; Kola, B.; Mantero, F.; Boscaro, M.; Arnaldi, G. High cardiovascular risk in patients with Cushing’s syndrome according to 1999 WHO/ISH guidelines. Clin. Endocrinol. 2004, 61, 768–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bujalska, I.J.; Kumar, S.; Stewart, P.M. Does central obesity reflect “Cushing’s disease of the omentum”? Lancet 1997, 349, 1210–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galton, D.J.; Wilson, J.P. Lipogenesis in adipose tissue of patients with obesity and Cushing’s disease. Clin. Sci. 1972, 43, 17P. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koch, R.; Sharma, A.M. Obesity and cardiovascular hemodynamic function. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 1999, 1, 127–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raison, J. Conséquences cardiovasculaires de l’obésité associée à l’hypertension artérielle [Cardiovascular consequences of obesity associated with arterial hypertension]. Presse Med. 1992, 21, 1522–1525. [Google Scholar]

- de Simone, G.; Devereux, R.B.; Kizer, J.R.; Chinali, M.; Bella, J.N.; Oberman, A.; Kitzman, D.W.; Hopkins, P.N.; Rao, D.C.; Arnett, D.K. Body composition and fat distribution influence systemic hemodynamics in the absence of obesity: The HyperGEN Study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2005, 81, 757–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krzesiński, P.; Gielerak, G.; Kowal, J. Kardiografia impedancyjna—Nowoczesne narzedzie terapii monitorowanej chorób układu krazenia [Impedance cardiography—A modern tool for monitoring therapy of cardiovascular diseases]. Kardiol. Pol. 2009, 67, 65–71. (In Polish) [Google Scholar]

- El-Dawlatly, A.; Mansour, E.; Al-Shaer, A.A.; Al-Dohayan, A.; Samarkandi, A.; Abdulkarim, A.; Alshehri, H.; Faden, A. Impedance cardiography: Noninvasive assessment of hemodynamics and thoracic fluid content during bariatric surgery. Obes. Surg. 2005, 15, 655–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eikås, J.G.; Gerdts, E.; Halland, H.; Midtbø, H.; Cramariuc, D.; Kringeland, E. Arterial Stiffness in Overweight and Obesity: Association with Sex, Age, and Blood Pressure. High Blood Press Cardiovasc. Prev. 2023, 30, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abomandour, H.G.; Elnagar, A.M.; Aboleineen, M.W.; Shehata, I.E. Subclinical Impairment of Left Ventricular Function assessed by Speckle Tracking in Type 2 Diabetic Obese and Non-Obese Patients: Case Control Study. J. Cardiovasc. Echogr. 2022, 32, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galderisi, M.; Lomoriello, V.S.; Santoro, A.; Esposito, R.; Olibet, M.; Raia, R.; Di Minno, M.N.; Guerra, G.; Mele, D.; Lombardi, G. Differences of myocardial systolic deformation and correlates of diastolic function in competitive rowers and young hypertensives: A speckle-tracking echocardiography study. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2010, 23, 1190–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalam, K.; Otahal, P.; Marwick, T.H. Prognostic implications of global LV dysfunction: A systematic review and meta-analysis of global longitudinal strain and ejection fraction. Heart 2014, 100, 1673–1680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurek, A.; Krzesiński, P.; Gielerak, G.; Witek, P.; Zieliński, G.; Kazimierczak, A.; Wierzbowski, R.; Banak, M.; Uziębło-Życzkowska, B. Cushing’s Disease: Assessment of Early Cardiovascular Hemodynamic Dysfunction With Impedance Cardiography. Front. Endocrinol. 2021, 12, 751743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurek, A.; Krzesiński, P.; Uziębło-Życzkowska, B.; Witek, P.; Zieliński, G.; Kazimierczak, A.; Wierzbowski, R.; Banak, M.; Gielerak, G. The patient’s sex determines the hemodynamic profile in patients with Cushing disease. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1270455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleseriu, M.; Auchus, R.; Bancos, I.; Ben-Shlomo, A.; Bertherat, J.; Biermasz, N.R.; Boguszewski, C.L.; Bronstein, M.D.; Buchfelder, M.; Carmichael, J.D.; et al. Consensus on diagnosis and management of Cushing’s disease: A guideline update. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021, 9, 847–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nieman, L.K.; Biller, B.M.; Findling, J.W.; Newell-Price, J.; Savage, M.O.; Stewart, P.M.; Montori, V.M. The diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2008, 93, 1526–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceccato, F.; Boscaro, M. Cushing’s syndrome: Screening and diagnosis. High. Blood Press. Cardiovasc. Prev. 2016, 23, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alberti, K.G.; Eckel, R.H.; Grundy, S.M.; Zimmet, P.Z.; Cleeman, J.I.; Donato, K.A.; Fruchart, J.C.; James, W.P.; Loria, C.M.; Smith, S.C., Jr.; et al. Harmonizing the metabolic syndrome: A joint interim statement of the International Diabetes Federation Task Force on Epidemiology and Prevention; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; American Heart Association; World Heart Federation; International Atherosclerosis Society; and International Association for the Study of Obesity. Circulation 2009, 120, 1640–1645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visseren, F.L.J.; Mach, F.; Smulders, Y.M.; Carballo, D.; Koskinas, K.C.; Bäck, M.; Benetos, A.; Biffi, A.; Boavida, J.M.; Capodanno, D.; et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. Eur. Heart J. 2021, 42, 3227–3337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, B.; Mancia, G.; Spiering, W.; Agabiti Rosei, E.; Azizi, M.; Burnier, M.; Clement, D.L.; Coca, A.; de Simone, G.; Dominiczak, A.; et al. 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. Eur. Heart J. 2018, 39, 3021–3104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lang, R.M.; Badano, L.P.; Mor-Avi, V.; Afilalo, J.; Armstrong, A.; Ernande, L.; Flachskampf, F.A.; Foster, E.; Goldstein, S.A.; Kuznetsova, T.; et al. Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: An update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2015, 28, 1–39.e14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagueh, S.F.; Smiseth, O.A.; Appleton, C.P.; Byrd, B.F.; Dokainish, H.; Edvardsen, T.; Flachskampf, F.A.; Gillebert, T.C.; Klein, A.L.; Lancellotti, P.; et al. Recommendations for the evaluation of left ventricular diastolic function by echocardiography: An update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2016, 29, 277–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voigt, J.U.; Pedrizzetti, G.; Lysyansky, P.; Marwick, T.H.; Houle, H.; Baumann, R.; Pedri, S.; Ito, Y.; Abe, Y.; Metz, S.; et al. Definitions for a common standard for 2D speckle tracking echocardiography: Consensus document of the EACVI/ASE/Industry Task Force to standardize deformation imaging. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 2015, 28, 183–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhalla, V.; Isakson, S.; Bhalla, M.A.; Lin, J.P.; Clopton, P.; Gardetto, N.; Maisel, A.S. Diagnostic Ability of B-Type Natriuretic Peptide and Impedance Cardiography: Testing to Identify Left Ventricular Dysfunction in Hypertensive Patients. Am. J. Hypertens. 2005, 18, 73S–81S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parrott, C.W.; Burnham, K.M.; Quale, C.; Lewis, D.L. Comparison of Changes in Ejection Fraction to Changes in Impedance Cardiography Cardiac Index and Systolic Time Ratio. Congest. Heart Fail. 2004, 10, 11–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packer, M.; Abraham, W.T.; Mehra, M.R.; Yancy, C.W.; Lawless, C.E.; Mitchell, J.E.; Smart, F.W.; Bijou, R.; O’Connor, C.M.; Massie, B.M.; et al. Utility of Impedance Cardiography for the Identification of Short-Term Risk of Clinical Decompensation in Stable Patients with Chronic Heart Failure. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2006, 47, 2245–2252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pauca, A.L.; O’Rourke, M.F.; Kon, N.D. Prospective evaluation of a method for estimating ascending aortic pressure from the radial artery pressure waveform. Hypertension 2001, 38, 932–937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coulden, A.; Hamblin, R.; Wass, J.; Karavitaki, N. Cardiovascular health and mortality in Cushing’s disease. Pituitary 2022, 25, 750–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clayton, R.N. Cardiovascular complications of Cushings syndrome: Impact on morbidity and mortality. J. Neuroendocrinol. 2022, 34, e13175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Leo, M.; Pivonello, R.; Auriemma, R.S.; Cozzolino, A.; Vitale, P.; Simeoli, C.; De Martino, M.C.; Lombardi, G.; Colao, A. Cardiovascular disease in Cushing’s syndrome: Heart versus vasculature. Neuroendocrinology 2010, 1, 50–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faggiano, A.; Pivonello, R.; Spiezia, S.; De Martino, M.C.; Filippella, M.; Di Somma, C.; Lombardi, G.; Colao, A. Cardiovascular risk factors and common carotid artery caliber and stiff ness in patients with Cushing’s disease during active disease and 1 year after disease remission. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003, 88, 2527–2533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Witek, P.; Zieliński, G.; Szamotulska, K.; Witek, J.; Zgliczyński, W. Complications of Cushing’s disease—Prospective evaluation and clinical characteristics. Do they affect the efficacy of surgical treatment? Endokrynol. Pol. 2012, 63, 277–285. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Geer, E.B.; Shen, W.; Gallagher, D.; Punyanitya, M.; Looker, H.C.; Post, K.D.; Freda, P.U. MRI assessment of lean and adipose tissue distribution in female patients with Cushing’s disease. Clin. Endocrinol. 2010, 73, 469–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, M. The role of glucocorticoid action in the pathophysiology of the metabolic syndrome. Nutr. Metab. 2005, 2, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tataranni, P.A.; Larson, D.E.; Snitker, S.; Young, J.B.; Flatt, J.P.; Ravussin, E. Eff ects of glucocorticoids on energy metabolism and food intake in humans. Am. J. Physiol. 1996, 271, E317–E325. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Isidori, A.M.; Graziadio, C.; Paragliola, R.M.; Cozzolino, A.; Ambrogio, A.G.; Colao, A.; Corsello, S.M.; Pivonello, R. ABC Study Group. The hypertension of Cushing’s syndrome: Controversies in the pathophysiology and focus on cardiovascular complications. J. Hypertens. 2015, 33, 44–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekkers, O.M.; Biermasz, N.R.; Pereira, A.M.; Roelfsema, F.; van Aken, M.O.; Voormolen, J.H.; Romijn, J.A. Mortality in patients treated for Cushing’s disease is increased, compared with patients treated for nonfunctioning pituitary macroadenoma. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007, 92, 976–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lambert, J.K.; Goldberg, L.; Fayngold, S.; Kostadinov, J.; Post, K.D.; Geer, E.B. Predictors of mortality and long-term outcomes in treated Cushing’s disease: A study of 346 patients. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 98, 1022–1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abel, E.D.; Litwin, S.E.; Sweeney, G. Cardiac remodeling in obesity. Physiol. Rev. 2008, 88, 389–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hey, T.M.; Dahl, J.S.; Brix, T.H.; Søndergaard, E.V. Biventricular hypertrophy and heart failure as initial presentation of Cushing’s disease. BMJ Case Rep. 2013, bcr2013201307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toja, P.M.; Branzi, G.; Ciambellotti, F.; Radaelli, P.; De Martin, M.; Lonati, L.M.; Scacchi, M.; Parati, G.; Cavagnini, F.; Cavagnini, F. Clinical relevance of cardiac structure and function abnormalities in patients with Cushing’s syndrome before and after cure. Clin. Endocrinol. 2012, 76, 332–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, K.H.; Marsan, N.A.; Delgado, V.; Biermasz, N.R.; Holman, E.R.; Smit, J.W.; Feelders, R.A.; Bax, J.J.; Pereira, A.M. Increased myocardial fibrosis and left ventricular dysfunction in Cushing’s syndrome. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2012, 166, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baykan, M.; Erem, C.; Gedikli, O.; Hacihasanoglu, A.; Erdogan, T.; Kocak, M.; Kaplan, S.; Kiriş, A.; Orem, C.; Celik, S. Assessment of left ventricular diastolic function and Tei index by tissue Doppler imaging in patients with Cushing’s Syndrome. Echocardiography 2008, 25, 182–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ainscough, J.F.; Drinkhill, M.J.; Sedo, A.; Turner, N.A.; Brooke, D.A.; Balmforth, A.J.; Ball, S.G. Angiotensin II type-1 receptor activation in the adult heart causes blood pressure-independent hypertrophy and cardiac dysfunction. Cardiovasc. Res. 2009, 81, 592–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uziębło-Życzkowska, B.; Krzesinński, P.; Witek, P.; Zielinński, G.; Jurek, A.; Gielerak, G.; Skrobowski, A. Cushing’s Disease: Subclinical Left Ventricular Systolic and Diastolic Dysfunction Revealed by Speckle Tracking Echocardiography and Tissue Doppler Imaging. Front. Endocrinol. 2017, 8, 222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eschalier, R.; Rossignol, P.; Kearney-Schwartz, A.; Adamopoulos, C.; Karatzidou, K.; Fay, R.; Mandry, D.; Marie, P.Y.; Zannad, F. Features of cardiac remodeling, associated with blood pressure and fibrosis biomarkers, are frequent in subjects with abdominal obesity. Hypertension 2014, 63, 740–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzesiński, P.; Stańczyk, A.; Piotrowicz, K.; Gielerak, G.; Uziębło-Zyczkowska, B.; Skrobowski, A. Abdominal obesity and hypertension: A double burden to the heart. Hypertens. Res. 2016, 39, 349–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, C.Y.; O’Moore-Sullivan, T.; Leano, R.; Byrne, N.; Beller, E.; Marwick, T.H. Alterations of left ventricular myocardial characteristics associated with obesity. Circulation 2004, 110, 3081–3087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parrinello, G.; Licata, A.; Colomba, D.; Di Chiara, T.; Argano, C.; Bologna, P.; Corrao, S.; Avellone, G.; Scaglione, R.; Licata, G. Left ventricular filling abnormalities and obesity-associated hypertension: Relationship with overproduction of circulating transforming growth factor beta1. J. Hum. Hypertens. 2005, 19, 543–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Q.; Gao, Y.; Tan, K.; Li, P. Subclinical impairment of left ventricular function in diabetic patients with or without obesity: A study based on three-dimensional speckle tracking echocardiography. Herz 2014, 40, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feraco, A.; Marzolla, V.; Scuteri, A.; Armani, A.; Caprio, M. Mineralocorticoid Receptors in Metabolic Syndrome: From Physiology to Disease. Trends Endocrinol. Metab. 2020, 31, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content.

|

Filed under: Cushing's | Tagged: Cushing's Disease, Hemodynamic changes, obesity | Leave a comment »