Abstract

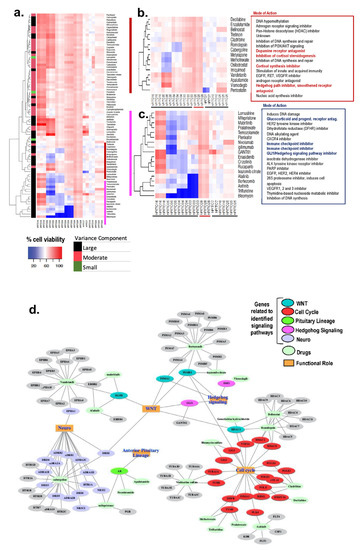

We investigated the impact of metformin on ACTH secretion and tumorigenesis in pituitary corticotroph tumors. The mouse pituitary tumor AtT20 cell line was treated with varying concentrations of metformin. Cell viability was assessed using the CCK-8 assay, ACTH secretion was measured using an ELISA kit, changes in the cell cycle were analyzed using flow cytometry, and the expression of related proteins was evaluated using western blotting. RNA sequencing was performed on metformin-treated cells. Additionally, an in vivo BALB/c nude xenograft tumor model was established in nude mice, and immunohistochemical staining was conducted for further verification. Following metformin treatment, cell proliferation was inhibited, ACTH secretion decreased, and G1/S phase arrest occurred. Analysis of differentially expressed genes revealed cancer-related pathways, including the MAPK pathway. Western blotting confirmed a decrease in phosphorylated ERK1/2 and phosphorylated JNK. Combining metformin with the ERK1/2 inhibitor Ulixertinib resulted in a stronger inhibitory effect on cell proliferation and POMC (Precursors of ACTH) expression. In vivo studies confirmed that metformin inhibited tumor growth and reduced ACTH secretion. In conclusion, metformin inhibits tumor progression and ACTH secretion, potentially through suppression of the MAPK pathway in AtT20 cell lines. These findings suggest metformin as a potential drug for the treatment of Cushing’s disease.

Introduction

Pituitary neuroendocrine tumors (PitNETs) are common intracranial tumors with an incidence of 1/1000, and pituitary corticotroph tumors (corticotroph PitNETs) account for approximately 15% of all PitNETs. Most corticotroph PitNETs are functional tumors with clinical manifestations of Cushing’s disease characterized by central obesity, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and psychosis (Cui et al., 2021). The increased cortisol due to the overproduction of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) significantly reduces the overall quality of survival and life expectancy of patients (Sharma et al., 2015; Barbot et al., 2018). Currently, treatment of corticotroph PitNETs mainly relies on surgery resection, pharmacologic therapy or radiotherapy may be considered for patients with residual tumors or those who are unable to undergo surgery. While several agents, such as cabergoline and pasireotide, are clinically approved, the effect is unsatisfactory, and potentially serious side effects exist. Therefore, there is an urgent need to develop novel therapeutic drugs for corticotroph PitNETs.

Metformin is a biguanide hypoglycemic agent for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. In addition to its hypoglycemic effect, numerous studies identified the therapeutic role of metformin in the prevention and treatment of various tumors including small cell lung cancer, colorectal cancer, breast cancer, ovarian cancer, and neuroendocrine tumors (Lu et al., 2022; Kamarudin et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2019; Thakur et al., 2019), making metformin a promising adjuvant drug in the therapy of cancers. Besides, it has been reported that metformin improves metabolic and clinical outcomes in patients treated with glucocorticoids. However, to date, limited studies explore the potential anti-cancer effect of metformin in corticotroph PitNETs. Recent studies report the use of metformin for blood glucose and body weight control in patients with Cushing’s disease (Ceccato et al., 2015), while the role of metformin on ACTH secretion and tumor growth in corticotroph PitNETs remains to be elucidated.

In the current study, we investigated the effect of metformin in corticotroph PitNETs and performed RNA-sequencing to identify the potential mechanisms of metformin. We found that metformin inhibited cell proliferation and ACTH secretion of AtT20 cells in a dose-dependent manner. Besides, metformin induced cell cycle arrest via decreased ERK1/2 phosphorylation and increased P38 phosphorylation. Our results revealed that metformin is a potential drug for corticotroph PitNET therapy.

Section snippets

Cell culture

The ACTH-secreting mouse pituitary tumor cell line AtT-20 was purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA, USA). Cells were cultured in F-12K medium (ATCC; Catalog No. 30-2004), supplemented with 15% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Gibco), and 2.5% horse serum (Gibco) as suggested. AtT20 cells were cultured in a humidified incubator at 37 °C in 5% CO2.

Reagents and drugs

Metformin and Ulixertinib were purchased from MedChemExpress (MCE), Metformin was dissolved in sterile H2O and prepared as a

Results

Metformin inhibits cell proliferation and ACTH secretion, and leads to cell cycle arrest in AtT20 cells.

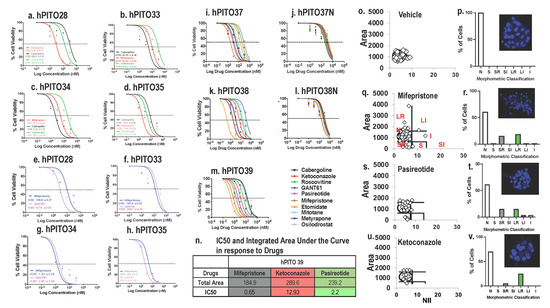

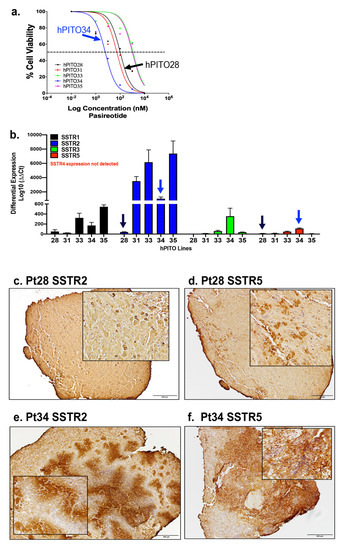

We used CCK-8 assay to detect the cell viability of AtT20 cells after treatment with different concentrations of metformin at 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h. The results showed that metformin significantly inhibited the proliferation of AtT20 cells in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 1A). Similarly, prolonged (6 days) treatment of AtT20 cells with a lower concentration (400 μM) of metformin also inhibited

Discussion

Metformin, acting by binding to PEN2 and initiating the subsequent AMPK signaling pathway in lysosomes, is the most commonly used oral hypoglycemic agent (Hundal et al., 2000; Ma et al., 2022). Previous reports demonstrated metformin as a potential anti-tumor agent in cancer therapy (Evans et al., 2005). Metformin, either alone or in combination with other drugs, has been shown to reduce cancer risk in a variety of tumors including pituitary neuroendocrine tumors (PitNETs) (Thakur et al., 2019;

Conclusion

Our study demonstrated that metformin suppressed cell proliferation and decreased ACTH secretion in AtT20 cells via the MAPK pathway. Our results revealed that metformin is a potential anti-tumor drug for the therapy of corticotroph PitNETs, which deserves further study.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82072804, 82071559).

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Yingxuan Sun: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Jianhua Cheng: Data curation, Formal analysis, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Ding Nie: Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. Qiuyue Fang: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. Chuzhong Li: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition. Yazhuo Zhang:

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

We thank Mr. Hua Gao (Cell Biology Laboratory, Beijing Neurosurgical Institute, China) for support with the techniques.

References (30)

- K. Jin et al.

Metformin suppresses growth and adrenocorticotrophic hormone secretion in mouse pituitary corticotroph tumor AtT20 cells

Mol. Cell. Endocrinol.

(2018) - R. Krysiak et al.

The effect of metformin on prolactin levels in patients with drug-induced hyperprolactinemia

Eur. J. Intern. Med.

(2016) - X. Liu et al.

Combination treatment with bromocriptine and metformin in patients with bromocriptine-resistant prolactinomas: pilot study

World neurosurgery

(2018) - J. Sinnett-Smith et al.

Metformin inhibition of mTORC1 activation, DNA synthesis and proliferation in pancreatic cancer cells: dependence on glucose concentration and role of AMPK

Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun.

(2013) - C.R. Triggle et al.

Metformin: is it a drug for all reasons and diseases?

Metab., Clin. Exp.

(2022) - J.C. Wang et al.

Metformin inhibits metastatic breast cancer progression and improves chemosensitivity by inducing vessel normalization via PDGF-B downregulation

J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. : CR

(2019) - J. An et al.

Metformin inhibits proliferation and growth hormone secretion of GH3 pituitary adenoma cells

Oncotarget

(2017) - M. Barbot et al.

Diabetes mellitus secondary to Cushing’s disease

Front. Endocrinol.

(2018) - F. Ceccato et al.

Clinical use of pasireotide for Cushing’s disease in adults

Therapeut. Clin. Risk Manag.

(2015) - M. Cejuela et al.

Metformin and breast cancer: where are we now?

Int. J. Mol. Sci.

(2022)

Filed under: Cushing's, Treatments | Tagged: ACTH, AtT20 Cells, Cushing Disease, metformin, pituitary, pituitary corticotroph tumors | Leave a comment »