Abstract

Context

Arginine-vasopressin and CRH act synergistically to stimulate secretion of ACTH. There is evidence that glucocorticoids act via negative feedback to suppress arginine-vasopressin secretion.

Objective

Our hypothesis was that a postoperative increase in plasma copeptin may serve as a marker of remission of Cushing disease (CD).

Design

Plasma copeptin was obtained in patients with CD before and daily on postoperative days 1 through 8 after transsphenoidal surgery. Peak postoperative copeptin levels and Δcopeptin values were compared among those in remission vs no remission.

Results

Forty-four patients (64% female, aged 7-55 years) were included, and 19 developed neither diabetes insipidus (DI) or syndrome of inappropriate anti-diuresis (SIADH). Thirty-three had follow-up at least 3 months postoperatively. There was no difference in peak postoperative copeptin in remission (6.1 pmol/L [4.3-12.1]) vs no remission (7.3 pmol/L [5.4-8.4], P = 0.88). Excluding those who developed DI or SIADH, there was no difference in peak postoperative copeptin in remission (10.2 pmol/L [6.9-21.0]) vs no remission (5.4 pmol/L [4.6-7.3], P = 0.20). However, a higher peak postoperative copeptin level was found in those in remission (14.6 pmol/L [±10.9] vs 5.8 (±1.4), P = 0.03]) with parametric testing. There was no difference in the Δcopeptin by remission status.

Conclusions

A difference in peak postoperative plasma copeptin as an early marker to predict remission of CD was not consistently present, although the data point to the need for a larger sample size to further evaluate this. However, the utility of this test may be limited to those who develop neither DI nor SIADH postoperatively.

Arginine vasopressin (AVP) and CRH act synergistically as the primary stimuli for secretion of ACTH, leading to release of cortisol [1, 2]. The role of AVP in the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis is via release from the parvocellular neurons of the paraventricular nuclei (and possibly also from the magnocellular neurons of the paraventricular and supraoptic nuclei), the secretion of which is stimulated by stress [3-6]. AVP release results in both independent stimulation of ACTH release and potentiation of the effects of CRH [3, 7-9]. Additionally, there is evidence that glucocorticoids act by way of negative feedback to suppress AVP secretion [10, 11-20]. Further, parvocellular neurons of the hypothalamic paraventricular nuclei have been shown to increase AVP production and neurosecretory granule size after adrenalectomy, and inappropriately elevated plasma AVP has been reported in the setting of adrenal insufficiency with normalization of plasma AVP after glucocorticoid administration [21-24]. This relationship of AVP and its effect on the HPA axis has been used in the diagnostic evaluation of Cushing syndrome (CS) [14] and evaluation of remission after transsphenoidal surgery (TSS) in Cushing disease (CD) by administration of desmopressin [25].

Copeptin makes up the C-terminal portion of the AVP precursor pre-pro-AVP. Copeptin is released from the posterior pituitary in stoichiometric amounts with AVP, and because of its longer half-life in circulation, it is a stable surrogate marker of AVP secretion [26-28]. Plasma copeptin has been studied in various conditions of the anterior pituitary. In a study by Lewandowski et al, plasma copeptin was measured after administration of CRH in assessment of HPA-axis function in patients with a variety of pituitary diseases. An increase in plasma copeptin was observed only in healthy subjects but not in those with pituitary disease who had an appropriately stimulated serum cortisol, and the authors concluded that copeptin may be a sensitive marker to reveal subtle alterations in the regulation of pituitary function [7]. Although in this study and others, plasma copeptin was assessed after pituitary surgery, it has not, to the best of our knowledge, been studied as a marker of remission of CD before and after pituitary surgery [7, 29].

In this study, plasma copeptin levels were assessed as a surrogate of AVP secretion before and after TSS for treatment of CD. Because there is evidence that glucocorticoids exert negative feedback on AVP, we hypothesized that there would be a greater postoperative increase in plasma copeptin in those with CD in remission after TSS resulting from resolution of hypercortisolemia and resultant hypocortisolemia compared with those not in remission with persistent hypercortisolemia and continued negative feedback. In other words, we hypothesized that an increase in copeptin could be an early marker of remission of CD after TSS. We aimed to complete this assessment by comparison of the peak postoperative copeptin and change in copeptin from preoperative to peak postoperative copeptin for those in remission vs not in remission postoperatively.

Subjects and Methods

Subjects

Adult and pediatric patients with CD who presented at the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development under protocol 97-CH-0076 and underwent TSS between March 2016 and July 2019 were included in the study. Exclusion criteria included a prior TSS within 6 weeks of the preoperative plasma copeptin sample or a preoperative diagnosis of diabetes insipidus, renal disease, or cardiac failure. Written informed consent was provided by patients aged 18 years and older and by legal guardians for patients aged < 18 years to participate in this study. Written informed assent was provided by patients aged 7 years to < 18 years. The 97-CH-0076 study (Investigation of Pituitary Tumors and Related Hypothalamic Disorders) has been approved by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development institutional review board.

Clinical and Biochemical Data

Clinical data were extracted from electronic medical records. Age, sex, body weight, body mass index (BMI), pubertal stage (in pediatric patients only), and history of prior TSS were obtained preoperatively during the admission for TSS. Clinical data obtained postoperatively included TSS date, histology, development of central diabetes insipidus (DI) or (SIADH), time from TSS to most recent follow-up, and clinical remission status at postoperative follow-up.

Preoperatively, serum sodium, 24-hour urinary free cortisol (UFC), UFC times the upper limit of normal (UFC × ULN), midnight (MN) serum cortisol, MN plasma ACTH, and 8 AM plasma ACTH were collected. Postoperatively, serum sodium, serum and urine osmolality, urine specific gravity, serum cortisol, and plasma ACTH were collected. For serum cortisol values < 1 mcg/dL, a value of 0.5 mcg/dL was assigned for the analyses; for plasma ACTH levels < 5 pg/mL, a value of 2.5 pg/mL was assigned.

Additionally, plasma copeptin levels were obtained preoperatively and on postoperative days (PODs) 1 through 8 after TSS at 8:00 AM. Peak postoperative copeptin was the highest plasma copeptin on PODs 1 through 8. The delta copeptin (Δcopeptin) was determined by subtracting the preoperative copeptin from the peak postoperative copeptin; hence, a positive change indicated a postoperative increase in plasma copeptin. Plasma copeptin was measured using an automated immunofluorescent sandwich assay on the BRAHMS Kryptor Compact PLUS Copeptin-proAVP. The limit of detection for the assay was 1.58 pmol/L, 5.7% intra-assay coefficient of variation, and 11.2% inter-assay coefficient of variation, with a lower limit of analytical measurement of 2.8 pmol/L. For those with multiple preoperative plasma copeptin values within days before surgery, an average of preoperative copeptin levels was used for analyses.

Diagnosis of CD was based on guidelines published by the Endocrine Society and as previously described for the adult and pediatric populations [30, 31]; diagnosis was further confirmed by either histologic identification of an ACTH-secreting pituitary adenoma in the resected tumor specimen, decrease in cortisol and ACTH levels postoperatively, and/or clinical remission after TSS at follow-up evaluation. All patients were treated with TSS at the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center by the same neurosurgeon. Remission after surgical therapy was based on serum cortisol of < 5 μg/dL during the immediate postoperative period, improvement of clinical signs and symptoms of cortisol excess at postoperative follow up, nonelevated 24-hour UFC at postoperative follow-up, nonelevated midnight serum cortisol at postoperative follow up when available, and continued requirement for glucocorticoid replacement at 3 to 6 months’ postoperative follow-up.

Diagnosis of SIADH was based on development of hyponatremia (serum sodium < 135 mmol/L) and oliguria (urine output < 0.5 mL/kg/h). Diagnosis of DI was determined by development of hypernatremia (serum sodium > 145 mmol/L), dilute polyuria (urine output > 4 mL/kg/h), elevated serum osmolality, and low urine osmolality.

Statistical Analyses

Results are presented as median (interquartile range [IQR], calculated as 25th percentile-75th percentile) or mean ± SD, as appropriate, and frequency (percentage). Where appropriate, we compared results using parametric or nonparametric testing; however, the median (IQR) and the mean ± SD were both reported to allow for comparisons with the appropriate testing noted. Subgroup analyses were completed comparing those who developed water balance disorders included patients who developed DI only (but not SIADH), those who developed SIADH only (but not DI), and those with no water balance disorder; hence, for these subgroup analyses, those who developed both DI and SIADH postoperatively (n = 4) were excluded. Preoperative copeptin, peak postoperative copeptin, and Δcopeptin were compared between those with and without remission at follow-up, using either t test or Wilcoxon rank-sum test, depending on the distribution of data. These were done in all patients combined, as well as within each subgroup. The same tests were used for comparing other continuous variables (eg, age, BMI SD score [SDS], cortisol excess measures) between those with and without remission. Categorical data (eg, sex, Tanner stage) were analyzed using the Fisher exact test. Comparisons of copeptin levels among the subgroups (DI, SIADH, neither) were carried out using mixed models and the Kruskal-Wallis test, as appropriate. Post hoc pairwise comparisons were adjusted for multiplicity using the Bonferroni correction, and as applicable, only corrected P values are reported. Mixed models for repeated measures also analyzed copeptin, serum sodium, and cortisol data for PODs 1 through 8. In addition, maximum likelihood estimation (GENMOD) procedures analyzed the effects of copeptin and serum sodium on the remission at follow-up. Correlation analyses were done with Spearman ρ. All analyses were tested for the potential confounding effects of age, sex, BMI SDS, and pubertal status, and were adjusted accordingly. For plasma copeptin reported as < 2.8 pmol/L, a value of 1.4 pmol/L (midpoint of 0 and 2.8 pmol/L) was used; sensitivity analyses repeated all relevant comparisons using the threshold limit of 2.8 pmol/L instead of 1.4 pmol/L. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% CIs, other magnitudes of the effect, data variability, and 2-sided P values provided the statistical evidence for the conclusions. Statistical analyses were performed in SAS version 9.4 software (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC).

Results

Patient Characteristics

Forty-four adult and pediatric patients, aged 7 to 55 years (77.2% were < 18 years old), with CD were included in the study. The cohort included 28 female patients (64%), and the median BMI SDS was 2.2 (1.1-2.5). Thirty-four percent (15/44) had prior pituitary surgery (none within the prior 6 weeks). Seventy-five percent (33/44) had postoperative follow-up evaluations available, with median follow-up of 13.5 months (11.3-16.0). Of those 33 patients, 85% were determined to be in remission at follow-up. Comparing those in remission vs no remission, there was no difference in age, sex, BMI SDS, pubertal status (in pediatric ages only), preoperative measures of cortisol excess (UFC × ULN, PM serum cortisol, MN plasma ACTH, AM plasma ACTH), duration of follow-up, or development of DI or SIADH. There was a lower postoperative serum cortisol nadir in those in remission at follow-up compared with those not in remission at follow-up, as expected, because a postoperative serum cortisol < 5 μg/dL was included in defining remission status. Postoperatively, 8/44 (18%) developed DI, 13/44 (30%) developed SIADH, 4/44 (9%) developed both DI and SIADH, and 19/44 (43%) developed no water balance disorder (Table 1). There were no differences by remission status when assessing these subgroups (ie, DI, SIADH, and no water balance disorder) separately.

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of subjects

|

All subjects, n = 44 |

All subjects by remission status, n = 33 |

|

|

All subjects by remission status, excluding those with DI or SIADH, n = 13 |

|

|

|

|

Remission, n = 28 |

No remission, n = 5 |

P |

Remission,

n = 10 |

No remission, n = 3 |

P |

| Age, median (range), y |

14.5 (7-55) |

17.4 ± 10.7

14.5 (12.5-17.5) |

15.6 ± 13.2

11.0 (9.0-12.0) |

0.11 |

13.7 ± 3.1

14.0 (13.0-15.0) |

19.7 ± 16.8

11.0 (9.0-39.0) |

0.60a |

Sex

Female |

28 (64%) |

22 (78.6%) |

3 (60.0%) |

0.57 |

9 (90.0%) |

2 (66.7%) |

0.42 |

| BMI SDS |

2.2 (1.1-2.5) |

1.7 ± 1.0

2.0 (0.9-2.5) |

2.2 ± 0.4

2.2 (2.1-2.3) |

0.70 |

1.7 ± 1.1

2.0 (0.7-2.5) |

2.0 ± 0.4

2.1 (1.5-2.3) |

0.65a |

| Pubertal status |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Female |

(n = 19) |

(n = 15) |

(n = 2) |

0.51 |

(n = 8) |

(n = 1) |

0.44 |

| Tanner 1-2 |

6 |

4 (26.7%) |

1 (50.0%) |

|

3 (37.5%) |

1 (25.0%) |

|

| Tanner 3-5 |

13 |

11 (73.3%) |

1 (50.0%) |

|

5 (62.5%) |

0 |

|

| Male |

(n = 14) |

(n = 5) |

(n = 2) |

|

(n = 1) |

(n = 1) |

— |

| Testicular volume < 12, mL |

10 |

4 (80.0%) |

2 (10.00%) |

|

1 (100.0%) |

1 (100.0%) |

|

| Testicular volume ≥ 12, mL |

4 |

1 (20.0%) |

0 |

1.0 |

0 |

0 |

|

| Preoperative UFC ULN |

3.3 (1.2-6.1) |

4.9 ± 6.1

2.6 (1.0-7.6) |

3.2 ± 1.3

3.7 (3.0-3.9) |

0.70 |

7.2 ± 8.4

3.9 (1.8-9.1) |

3.8 ± 0.7

3.9 (3.0-4.4) |

0.93 |

| Preoperative PM cortisol |

11.9 (9.2-14.8) |

13.3 ± 4.7

12.2 (9.2-16.8) |

10.8 ± 2.1

11.5 (9.0-11.6) |

0.30 |

13.3 ± 6.0

11.2 (8.4-16.5) |

11.1 ± 2.6

11.6 (8.3-13.6) |

0.57a |

| Preoperative MN ACTH |

43.4 (29.3-51.6) |

44.2 ± 25.5

46.1 (27.6-50.5) |

40.9 ± 15.3

11.5 (9.0-11.6) |

0.74 |

36.6 ± 16.6

37.4 (29.1-48.8) |

34.0 ± 9.4

39.3 (23.1-39.5) |

0.67 |

| Preoperative AM ACTH |

44.6 (31.4-60.5) |

46.9 ± 28.9

44.0 (29.8-56.2) |

48.6 ± 28.8

58.7 (21.7-60.5) |

0.84 |

35.2 ± 16.2

40.3 (28.0-44.0) |

45.4 ± 24.6

58.7 (17.0-60.5) |

0.41a |

| Postoperative cortisol nadir |

0.5 (0.5-0.5) |

0.7 ± 0.7

0.5 (0.5-0.5) |

7.8 ± 6.6

5.2 (2.2-12.3) |

<0.001 |

0.6 ± 0.3

0.5 (0.5-0.5) |

8.1 ± 7.9

5.2 (2.1-17.0) |

0.003 |

| Duration of follow-up |

13.5 (11.3-16.0) |

15.3 ± 7.9

14.0 (12.0-16.5) |

14.0 ± 13.0

11.0 (6.0-14.0) |

0.30 |

18.6 ± 11.2

15.5 (12.0-27.0) |

16.7 ± 17.2

11.0 (3.0-36.0) |

0.82a |

| DI only |

8 (18%) |

7/8 (87.5%) |

1/8 (12.5%) |

0.91 |

— |

— |

— |

| SIADH only |

13 (30%) |

8/9 (88.9%) |

1/9 (11.1%) |

|

|

|

|

| Neither DI/SIADH |

19 (43%) |

10/13 (76.9%) |

3/13 (23.1%) |

|

|

|

|

| Both DI and SIADH |

4 (9%) |

3/3 (100%) |

0/3 |

|

|

|

|

Demographic and clinical characteristics of all subjects (n = 44) with Cushing disease. Data are also presented by remission status for all subjects with postoperative follow-up (n = 33) and by remission status after excluding those who developed DI or SIADH postoperatively with postoperative follow-up (n = 13). Both median (IQR) and mean ± SD reported to allow for comparisons, with P value provided using appropriate testing depending on distribution of data sets. Data are mean ± SD, median (25th-75th IQR), or frequency (percentage) are reported, except for age, which is presented as median (range).

Abbreviations: AM, 7:30-8 PM; BMI, body mass index; DI, diabetes insipidus; IQR, interquartile range; MN, midnight; N/A, not applicable; SDS, SD score; SIADH, syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis; UFC, urinary free cortisol; ULN, upper limit of normal. p-values below the threshold of 0.05 are in bold.

aP value indicates comparison using parametric testing, as appropriate for normally distributed data.

Preoperative copeptin levels were higher in males (7.0 pmol/L [5.1-9.6]) than in females (4.0 pmol/L [1.4-5.8], P = 0.004) (Fig. 1). Age was inversely correlated with preoperative copeptin (rs = -0.35, P = 0.030) and BMI SDS was positively correlated with preoperative copeptin (rs = 0.54, P < 0.001) (Fig. 2).

Figure 1.

Preoperative plasma copeptin and sex. Preoperative plasma copeptin in all patients, comparing by sex. A higher preoperative plasma copeptin was found in males (7.0 pmol/L [5.1-9.6]) than in females (4.0 pmol/L [1.4-5.8], P = 0.004). Horizontal lines = median. Whiskers = 25th and 75th interquartile ranges.

Figure 2.

Preoperative plasma copeptin and BMI SDS. Association of preoperative plasma copeptin and BMI SDS in all patients. A BMI SDS was positively associated with a preoperative plasma copeptin (rs = 0.54, P < 0.001). Shaded area = 95% confidence interval.

Copeptin Before and After Transsphenoidal Surgery for CD

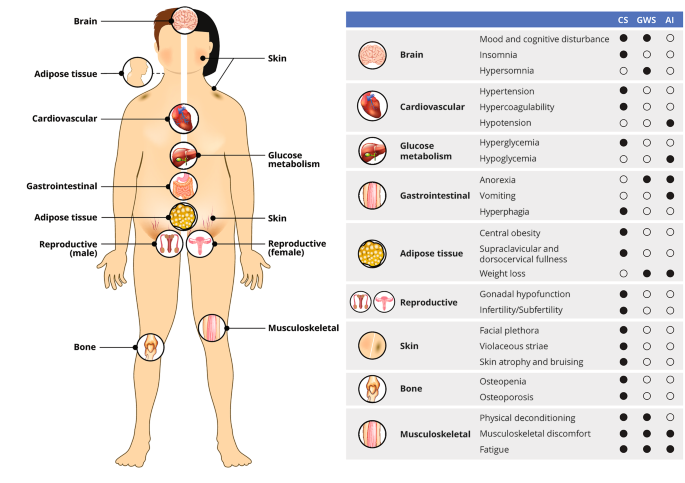

Among the 33 patients with postoperative follow-up, there was no difference in peak postoperative copeptin for patients in remission vs those not in remission (6.1 pmol/L [4.3-12.1] vs 7.3 pmol/L [5.4-8.4], P = 0.88). There was also no difference in the Δcopeptin for those in remission vs not in remission (2.3 pmol/L [-0.5 to 8.2] vs 0.1 pmol/L [-0.1 to 2.2], P = 0.46) (Fig. 3). Including all subjects, the mean preoperative copeptin was 5.6 pmol/L (±3.4). For patients with follow-up, there was no difference in preoperative copeptin for those in remission (4.8 pmol/L [±2.9]) vs no remission (6.0 pmol/L [±2.0], P = 0.47). POD 1 plasma copeptin ranged from < 2.8 to 11.3 pmol/L.

Figure 3.

(A) Peak postoperative plasma copeptin in all patients, comparing those in remission with no remission (6.1 pmol/L [4.3-12.1] vs 7.3 pmol/L [5.4-8.4], P = 0.88). (B) ΔCopeptin (preoperative plasma copeptin subtracted from postoperative peak plasma copeptin) in all patients, comparing those in remission with no remission (2.3 pmol/L [-0.5 to 8.2] vs 0.1 pmol/L [-0.1 to 2.2], P = 0.46). Horizontal lines = median. Whiskers = 25th and 75th interquartile ranges.

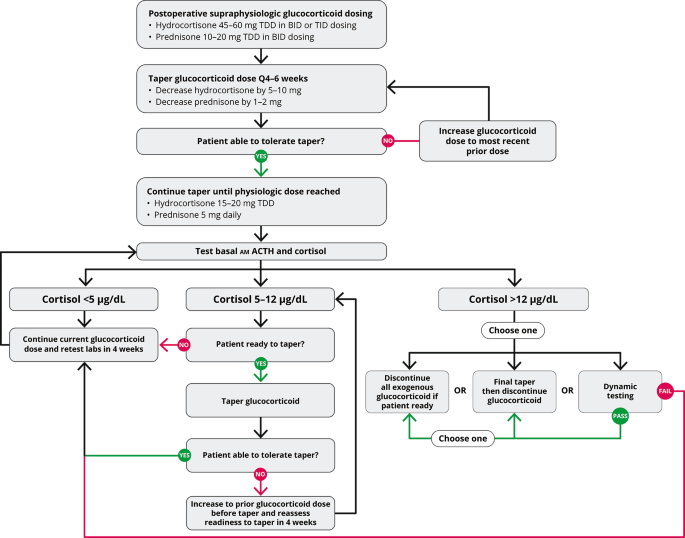

When those who developed DI or SIADH were excluded, there was no difference in peak postoperative copeptin in those in remission vs no remission (10.2 pmol/L [6.9-21.0] vs 5.4 pmol/L [4.6-7.3], P = 0.20). However, because the distribution of the peak postoperative copeptins was borderline normally distributed, parametric testing was also completed for this analysis, which showed a higher peak postoperative copeptin in remission (14.6 pmol/L [±10.9]) vs no remission (5.8 [±1.4], P = 0.03). There was no difference in the Δcopeptin for those in remission vs not in remission (5.1 pmol/L [0.3-19.5] vs 1.1 pmol/L [-0.1 to 2.2], P = 0.39) (Fig. 4). Preoperative copeptin was not different for those in remission (4.7 pmol/L [±2.4]) vs no remission (4.9 pmol/L [±20.3], P = 0.91). There was no association between serum cortisol and plasma copeptin over time postoperatively (Fig. 5).

Figure 4.

(A) Peak postoperative plasma copeptin excluding those who developed DI or SIADH, comparing those in remission with no remission (10.2 pmol/L [6.9-21.0] vs 5.4 pmol/L [4.6-7.3], P = 0.20). (B) ΔCopeptin (preoperative plasma copeptin subtracted from postoperative peak plasma copeptin) excluding those who developed DI or SIADH, comparing those in remission with no remission (5.1 pmol/L [0.3-19.5] vs 1.1 pmol/L [-0.1 to 2.2], P = 0.39). Horizontal lines = median. Whiskers = 25th and 75th interquartile ranges.

Figure 5.

Plasma copeptin and serum cortisol vs postoperative day for patients who did not develop DI or SIADH. Plasma copeptin (indicated by closed circle) and serum cortisol (indicated by “x”). Results shown as (median, 95% CI).

All analyses here were repeated adjusting for serum sodium, and there were no differences by remission status for preoperative, peak postoperative, or Δcopeptin for all subjects or after excluding those who developed a water balance disorder (data not shown).

Copeptin and Water Balance Disorders

As expected, peak postoperative copeptin appeared to be different among patients who developed DI, SIADH, and those without any fluid balance disorder (P = 0.029), whereas patients with DI had lower median peak postoperative copeptin (4.4 pmol/L [2.4-6.9]) than those who developed no fluid abnormality (10.0 pmol/L [5.4-16.5], P = 0.04), the statistical difference was not present after correction for multiple comparisons (P = 0.13). Peak postoperative copeptin of patients with SIADH was 9.4 pmol/L (6.5-10.4) and did not differ from patients with DI (P = 0.32) or those with no fluid abnormality (P = 1.0). There was a difference in Δcopeptin levels among these subgroups (overall P = 0.043), which appeared to be driven by the lower Δcopeptin in those who developed DI (-1.2 pmol/L [-2.6 to 0.1]) vs in those with neither DI or SIADH (3.1 pmol/L [0-9.6], P = 0.05). However, this pairwise comparison did not reach statistical significance, even before correction for multiple comparisons (P = 0.16) (Fig. 6). Preoperative copeptin levels were also not different among the subgroups (P = 0.54).

Figure 6.

(A) Peak postoperative plasma copeptin, comparing those who developed DI, SIADH, or neither (P = 0.029 for comparison of all 3 groups). (B) ∆ Copeptin (preoperative plasma copeptin subtracted from postoperative peak plasma copeptin), comparing those who developed DI, SIADH, or neither (P = 0.043 for comparison of all 3 groups). Horizontal lines = median. Whiskers = 25th and 75th interquartile ranges. Top brackets = pairwise comparisons. P values presented are after Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons.

Association of Sodium and Copeptin

Longitudinal data, adjusting for subgroups (ie, DI, SIADH, neither), were analyzed. As expected, there was a group difference (P = 0.003) in serum sodium over time (all DI was missing preoperative serum sodium), with the difference being driven by DI vs SIADH (P = 0.007), and SIADH vs neither (P = 0.012). There was no group difference in plasma copeptin over POD by water balance status (P = 0.16) over time (Fig. 7). There was also no effect by remission status at 3 to 6 months for either serum sodium or plasma copeptin.

Figure 7.

(A) Serum sodium and (B) plasma copeptin by POD and water balance status longitudinal data, adjusting for subgroups (ie, DI, SIADH, neither). Data points at point 0 on the x-axis indicate preoperative values. As expected, there was a group difference (P = 0.003) in serum sodium over time (all with DI were missing preoperative serum sodium), with the difference being driven by DI vs SIADH (P = 0.007), and SIADH vs neither (P = 0.012). There was no group difference in plasma copeptin over POD by water balance status (P = 0.16) over time.

Higher serum sodium levels from PODs 1 through 8 itself decreased the odds of remission (OR, 0.56; 95% CI, 0.42-0.73; P < 0.001) in all CD patients. Copeptin levels from these repeated measures adjusting for serum sodium did not correlate with remission status at 3 to 6 months’ follow-up (P = 0.38). There were no differences in preoperative, peak postoperative, or delta sodium levels by remission vs no remission in all patients and in those with no water balance disorders.

Discussion

AVP and CRH act synergistically to stimulate the secretion of ACTH and ultimately cortisol [1, 2], and there is evidence that glucocorticoids act by way of negative feedback to suppress AVP secretion [10, 11-20]. Therefore, we hypothesized that a greater postoperative increase in plasma copeptin in those with CD in remission after TSS because of resolution of hypercortisolemia and resultant hypocortisolemia, compared with those not in remission with persistent hypercortisolemia and continued negative feedback, would be observed. Although a clear difference in peak postoperative and Δcopeptin was not observed in this study, a higher peak postoperative copeptin was found in those in remission after excluding those who developed DI/SIADH when analyzing this comparison with parametric testing, and it is possible that we did not have the power to detect a difference by nonparametric testing, given our small sample size. Therefore, postoperative plasma copeptin may be a useful early marker to predict remission of CD after TSS. The utility of this test may be limited to those who do not develop water balance disorders postoperatively. If a true increase in copeptin occurs for those in remission after treatment of CD, it is possible that this could be due to the removal of negative feedback from cortisol excess on pre-pro-AVP secretion, as hypothesized in this study. However, it is also possible that other factors may contribute to an increase in copeptin postoperatively, including from the stress response of surgery and postoperative hypocortisolism and resultant stimulation of pre-pro-AVP secretion from these physical stressors and/or from unrecognized SIADH.

It was anticipated that more severe hypercortisolism to be negatively correlated with preoperative plasma copeptin because of greater negative feedback on AVP. However, no association was found between preoperative plasma copeptin and markers of severity of hypercortisolism (MN cortisol, AM ACTH, UFC × ULN) in this study. Similarly, we would expect that the preoperative plasma copeptin would be lower compared with healthy individuals. However, comparisons of healthy individuals may be difficult because the fluid and osmolality status at the time of the sample could influence the plasma copeptin, and depending on those factors, copeptin could be appropriately low. A healthy control group with whom to compare the preoperative values was not available for this study, and the thirsted state was not standardized for the preoperative copeptin measurements. Future studies could be considered to determine if preoperative plasma copeptin is lower in patients with CD, or other forms of CS, compared with healthy subjects, with all subjects thirsted for an equivalent period. Further, if preoperative plasma copeptin is found to be lower in thirsted subjects with CS than a thirsted healthy control group, the plasma copeptin could potentially be a diagnostic test to lend support for or against the diagnosis of endogenous CS.

In the comparisons of those who developed DI, SIADH, or neither, no difference was found in the Δcopeptin. Peak copeptin was lower in DI compared with those without DI or SIADH (but not different from SIADH). Again, it is possible that there is a lower peak postoperative copeptin and change in copeptin in those with DI, but we may not have had the power to detect this in all of our analyses. These comparisons of copeptin among those with or without water balance disorders postoperatively are somewhat consistent with a prior study showing postoperative copeptin as a good predictor of development of DI, in which a plasma copeptin < 2.5 pmol/L measured on POD 0 accurately identified those who developed DI, and plasma copeptin > 30 pmol/L ruled out the development of DI postoperatively [29]. In the current study, 3 of 6 subjects with DI had a POD 1 plasma copeptin < 2.5 pmol/L, and none had a POD 1 plasma copeptin > 30 pmol/L. However, the study by Winzeler et al found that copeptin measured on POD 0 (within 12 hours after surgery) had the greatest predictive value, and POD 0 plasma copeptin was not available in our study. Further, we used the preoperative, peak, and delta plasma copeptin for analyses, so the early low copeptin levels may not have been captured in our data and analyses.

Additionally, this study revealed that increasing levels of serum sodium have lower odds of remission. Those who have an ACTH-producing adenoma that is not identified by magnetic resonance imaging and visual inspection intraoperatively have lower rates of remission and are more likely to have greater manipulation of the pituitary gland intraoperatively [32-36], and the latter may result in greater damage to the pituitary stalk or posterior pituitary, increasing the risk for development of DI and resultant hypernatremia.

A higher preoperative copeptin was associated with male sex and increasing BMI SDS. Increasing preoperative copeptin was also found in pubertal boys compared with pubertal girls, with no difference in copeptin between prepubertal boys and girls. It is particularly interesting to note that these associations were only in the preoperative plasma copeptin levels, but not the postoperative peak copeptin or Δcopeptin. Because the association of higher plasma in adult males and pubertal males in comparison to adult females and pubertal females, respectively, have been reported by others [26, 37-40], it raises the question of a change in the association of sex and BMI with plasma copeptin in the postoperative state. An effect of BMI or sex was not found by remission status, so it does not seem that the postoperative hypocortisolemic state for those in remission could explain this loss of association. However, this study may not have been powered to detect this.

Strengths of this study include the prospective nature of the study. Further, this is the first study assessing the utility of copeptin to predict remission after treatment of CD. Limitations of this study include the small sample size because of the rarity of the condition, difficulty in clinically diagnosing DI and SIADH, potential effect of post-TSS fluid balance disorders (particularly for those who may have developed transient partial DI or transient SIADH), lack of long-term follow-up, lack of any postoperative follow-up in 11 of the 44 total subjects, as well the observational nature of the study. Further, it is possible that pubertal status, sex, and BMI may have affected copeptin levels, which may have not been consistently detected because of lack of power. Lack of data on the timing of hydrocortisone replacement is an additional limitation of this study because postoperative glucocorticoid replacement could affect AVP secretion via negative feedback. Additional studies are needed to assess to further assess the role of vasopressin and measurement of copeptin in patients before and after treatment of CD.

A clear difference in peak postoperative plasma copeptin as an early marker to predict remission of CD after TSS was not found. Further studies with larger sample sizes are needed to further evaluate postoperative plasma copeptin as an early marker to predict remission of CD, though the utility of this test may be limited to those who do not develop water balance disorders postoperatively. Future studies comparing copeptin levels before and after treatment of adrenal CS would be of particular interest because this would minimize the risk of postoperative DI or SIADH which also influence copeptin levels. Additionally, comparison of thirsted preoperative plasma copeptin in those with endogenous CS and thirsted plasma copeptin in healthy controls could potentially provide evidence of whether or not preoperative plasma copeptin is lower in patients with CD, or other forms of CS, compared with healthy subjects. Further, if this is found to be true, it could potentially be a diagnostic test to lend support for or against endogenous CS.

Abbreviations

-

AVP

-

BMI

-

CD

-

CS

-

DI

-

HPA

hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal

-

IQR

-

MN

-

OR

-

POD

-

SDS

-

SIADH

syndrome of inappropriate antidiuresis

-

TSS

-

UFC

-

ULN

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients and their families for participating in this study.

Funding

This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program, Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (NICHD), National Institutes of Health.

Disclosures

C.A.S. holds patents on technologies involving PRKAR1A, PDE11A, GPR101, and related genes, and his laboratory has received research funding support by Pfizer Inc. for investigations unrelated to this project. C.A.S. is associated with the following pharmaceutical companies: ELPEN, Inc., H. Lunbeck A/S, and Sync. Inc.

Clinical Trial Information

ClinicalTrials.gov registration no. NCT00001595 (registered November 4, 1999).

Data Availability

Some or all datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the Endocrine Society 2022.

This work is written by (a) US Government employee(s) and is in the public domain in the US.

Filed under: Cushing's, pituitary, Treatments | Tagged: copeptin, pituitary, remission, Transsphenoidal surgery | Leave a comment »

![author['full_name']](https://clf1.medpagetoday.com/media/images/author/kristenMonaco_188.jpg)

![Preoperative plasma copeptin and sex. Preoperative plasma copeptin in all patients, comparing by sex. A higher preoperative plasma copeptin was found in males (7.0 pmol/L [5.1-9.6]) than in females (4.0 pmol/L [1.4-5.8], P = 0.004). Horizontal lines = median. Whiskers = 25th and 75th interquartile ranges.](https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/jes/6/6/10.1210_jendso_bvac053/1/m_bvac053f0001.jpeg?Expires=1655299443&Signature=cGAP0Evman3rpz4yG5HWaDLcRC1jc1TJk93oOvoSu6VA1t1EWSDzSbl9EhdBf9JXp71MAF1oDWjp-6pLdnX31L06-LpLsjkSotr8DlUIvLNM9Z04l-gqSGf01AdXbLbpLDFsact6VqUeowhdAqNnh9zTcW0koOiQQHfFOhEUKieUoD1969Ae5bBh21~XnjFLQgGnckgxnVx3UCot7j~HS2iAi8ymdz0VDnNDzeooog4Youey2szlxX0O8LkEbCh0ZKP1evFH-tj6655-d9cYmGNUxBdO7SSIIcEnP9F29Lez~5JloMhqD~0RX2eL76VQ6iIWvd~wGdMmYQg~cIWFmw__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![(A) Peak postoperative plasma copeptin in all patients, comparing those in remission with no remission (6.1 pmol/L [4.3-12.1] vs 7.3 pmol/L [5.4-8.4], P = 0.88). (B) ΔCopeptin (preoperative plasma copeptin subtracted from postoperative peak plasma copeptin) in all patients, comparing those in remission with no remission (2.3 pmol/L [-0.5 to 8.2] vs 0.1 pmol/L [-0.1 to 2.2], P = 0.46). Horizontal lines = median. Whiskers = 25th and 75th interquartile ranges.](https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/jes/6/6/10.1210_jendso_bvac053/1/m_bvac053f0003.jpeg?Expires=1655299443&Signature=yW5PElkusuxtGjvn1AjQypt5XCd0KjXFXHAMhFsaWHhKnzKTixeryNbeCy109hsnlgnxVujb2SpQX04MH6oHBT2O6xo50vxQEcQgcC~ioyFJtMyk5-F24MkV0Szwr6~XIVOqNbs5adU91Y6AloIq2sUwxDPPrO8HHFwazLMXeZp8716bss98UtRM-SnpRYk~JoL4mfSg1jtwghv-1Jim5a3BoZEd6z7PJPx-RNz5jAsUeLvpwOW~4ylC6vEKs~3Wj4bc6VDPLA56TmowuV6I5NDgTiIErbtwKfRVn82d2216XXf72uaQc8rjp8pVNvLc6xrAneMt7C-sVuhxAPMEuQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)

![(A) Peak postoperative plasma copeptin excluding those who developed DI or SIADH, comparing those in remission with no remission (10.2 pmol/L [6.9-21.0] vs 5.4 pmol/L [4.6-7.3], P = 0.20). (B) ΔCopeptin (preoperative plasma copeptin subtracted from postoperative peak plasma copeptin) excluding those who developed DI or SIADH, comparing those in remission with no remission (5.1 pmol/L [0.3-19.5] vs 1.1 pmol/L [-0.1 to 2.2], P = 0.39). Horizontal lines = median. Whiskers = 25th and 75th interquartile ranges.](https://oup.silverchair-cdn.com/oup/backfile/Content_public/Journal/jes/6/6/10.1210_jendso_bvac053/1/m_bvac053f0004.jpeg?Expires=1655299443&Signature=IQ4ivUkf6XLkyDLGryzJjbHj9DhLWOhbnOr5ofRMRJY-NQbXQfMfEkvlD0q-zYHnLQMu~mnVWBdDsOxYYc-QiLAwqGX7qwUiOgqYy1r1U7XwmOHMASKP6EhdEpkdL7cxyof~1nGKjnCvvQMoP-r81P~Ce1N0Behb2CR8LrCfPYayWxRY0B5nPis3twtddA2vZxdH4iZpVUkqB~CA5BGsMynR62A~~XsFIQfB8kbnEPipNOWvd1A0-GzS-O520eo6TrPfLV3iqJ3wCo7oJ4Z42ziIcgxplWOX5EuaMU59tRTA6lgmT8GKFTg8yhpLgC-wevkk2LCSTWSk9Y3GMrKptQ__&Key-Pair-Id=APKAIE5G5CRDK6RD3PGA)