Abstract

Cyclic Cushing syndrome (CCS) is characterized by unpredictable, intermittent phases of excess cortisol, alternating with periods of normal or subnormal adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and cortisol levels. The mechanism is unclear. Due to its rarity and diverse clinical presentation, unpredictable phases, and various etiologies, CCS poses significant diagnostic and management challenges for endocrinologists. The authors describe 3 cases in which each patient’s initial presentation was a life-threatening hypercortisolemic phase that lasted from 4 days to 3 months, followed by spontaneous resolution to prolonged eucortisolemic phases lasting from 10 to 26 months. Further testing indicated an ectopic ACTH-secreting source; however, the locations of the offending tumors were indeterminate. The authors propose the term square wave CCS variant to characterize the unique, prolonged intercyclic phases of hypercortisolemia and eucortisolemia with this subtype that are distinct from conventional CCS characterized by shorter phases of transient hypercortisolemia shifting to periods of eucortisolemia or hypocortisolemia. This uncharacteristic pattern of cyclicity poses diagnostic and therapeutic challenges, thus underscoring the importance of careful diagnostic workup and treatment of these patients.

Introduction

Cyclic Cushing syndrome (CCS) is a rare variant of Cushing syndrome (CS) characterized by intermittent episodes of cortisol peaks alternating with variable periods of normal or subnormal adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and cortisol levels (troughs) [1]. These cycles can occur at regular or irregular intervals [2], with unpredictable intercyclic phases typically lasting from days to months [3, 4]. The prevalence of CCS in patients with CS is low, ranging from 8% to 19% [3‐6]. Several alternative terms (eg, intermittent, variable, periodic, and episodic hypercortisolism) have been proposed to characterize the variable cyclicity of ACTH and cortisol secretion in patients with CCS [7].

We describe 3 cases of suspected ectopic ACTH-dependent CS with an indeterminate ACTH source that presented with life-threatening hypercortisolemia lasting from 4 days to 3 months, followed by spontaneous eucortisolemic phases lasting from 10 to 26 months. The term square wave is proposed to describe this unique cyclic pattern to highlight the unpredictability of severe hypercortisolemia followed by spontaneous prolonged eucortisolemic phases, which is distinct from previously described transient regular or irregular cycles with shorter intercyclic phases of CCS that require medical intervention.

Case Presentation

Case 1

A 75-year-old man with atrial fibrillation, bilateral leg edema, 6-month weight loss of 7 pounds (3.2 kg), and generalized muscle weakness was referred for cardiac ablation therapy. However, just before he underwent the procedure, he was found to be profoundly hypokalemic with potassium of 2.9 mEq/L (SI: 2.9 mmol/L) (reference range, 3.6-5.3 mEq/L [SI: 3.6-5.3 mmol/L]) and hyperglycemic, with blood glucose of 498 mg/dL (SI: 27.8 mmol/L) (reference range, 70-99 mg/dL [SI: 3.9-5.5 mmol/L]) and glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) of 7.4%. He was emergently treated with potassium supplementation and insulin therapy.

Case 2

A 61-year-old woman presented to the emergency department with palpitations, uncontrolled hypertension, weight loss of 20 pounds (9.1 kg) over 2 weeks, new signs of hyperandrogenism (eg, hirsutism, acne, muscle atrophy), lower back pains, easy bruising, and proximal muscle weakness.

Case 3

A 57-year-old woman presented to the emergency department in August 2021 with a 2-month history of facial swelling and generalized muscle weakness. She had reported a similar episode in April 2019 with hypokalemia (potassium, 2.5 mEq/L [SI: 2.5 mmol/L]) that was treated with potassium repletion therapy.

Diagnostic Assessment

Case 1

Further laboratory tests revealed elevated morning (Am) cortisol of 76.8 µg/dL (SI: 2119 nmol/L) (reference range, 5-25 µg/dL [SI: 138-690 nmol/L]), Am ACTH of 368 pg/mL (SI: 81 pmol/L) (reference range, 6-50 pg/mL [SI: 1.3-11.0 pmol/L]), and 24-hour urine free cortisol (UFC) of 4223 µg/24 hours (SI: 11 656 nmol/24 hours) (reference range, 1.5-18.1 µg/24 hours [SI: 4-50 nmol/24 hours]) (Table 1). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pituitary (Fig. 1) and 68Ga-DOTATATE positron emission tomography (PET) (Table 2) of the chest, pelvis, and abdomen failed to identify the source of ACTH secretion. Inferior petrosal sinus sampling (IPSS) showed no significant ACTH gradient, supporting the likelihood of an ectopic ACTH-secreting source (Table 3).

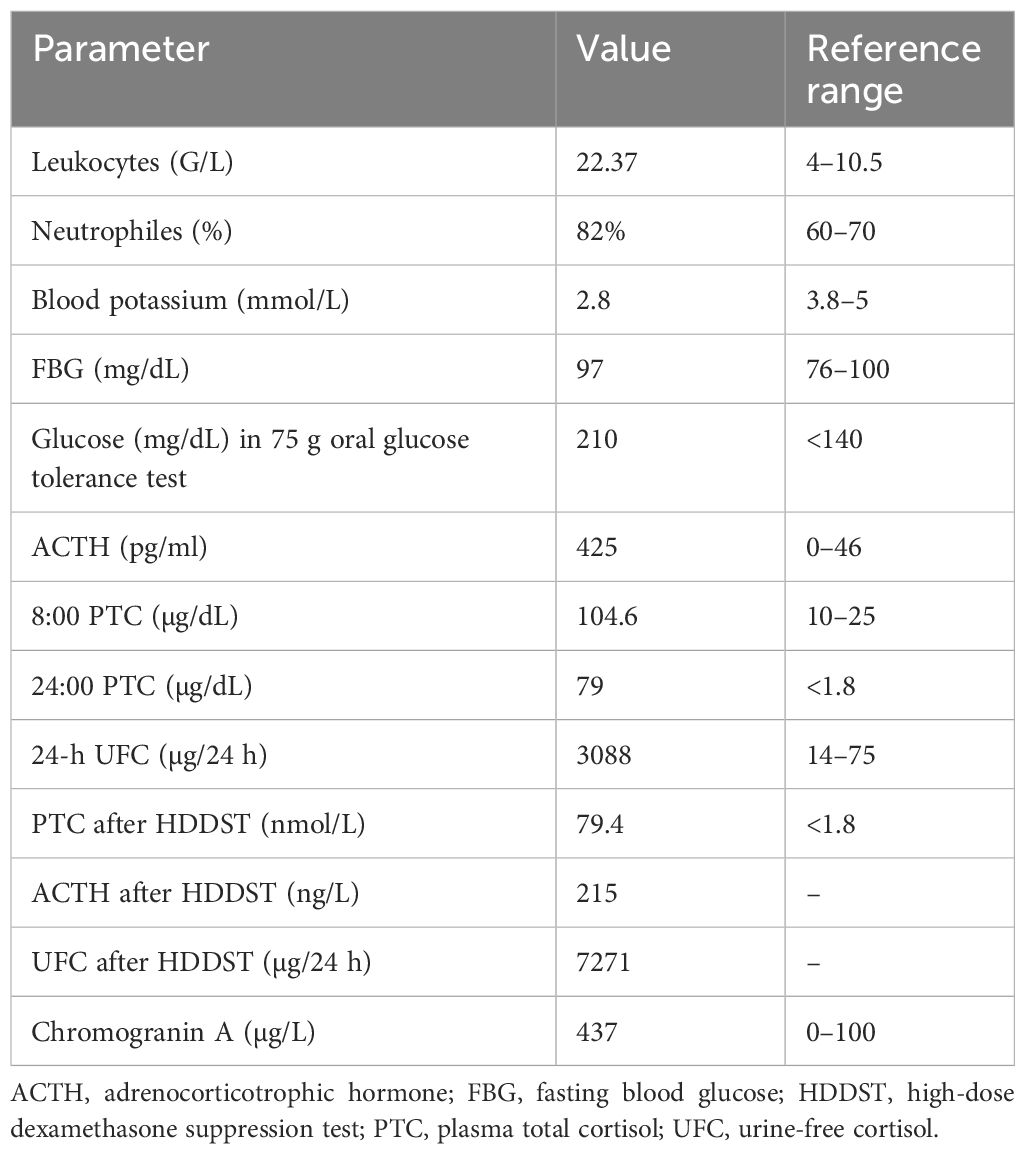

Table 1.

Summary of biochemical testing data for the 3 patients with a square wave pattern of cyclic Cushing syndrome

| Test, reference range | Patient 1 (male, 75 years) | Patient 2 (female, 61 years) | Patient 3 (female, 57 years) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IP | EP | IP | EP | IP | EP | |

| AM cortisol 5-23 µg/dL (138-690 nmol/L) | 76.8 µg/dL (2119 nmol/L) | 14.2 µg/dL (392 nmol/L) | 38.4 µg/dL (1060 nmol/L) | 17.9 µg/dL (494 nmol/L) | 56.8 µg/dL (1568 nmol/L) | 14.4 µg/dL (397 nmol/L) |

| AM ACTH 6-50 pg/mL (1.3-11.0 pmol/L) | 368 pg/mL (81 pmol/L) | 38.1 pg/mL (8.4 pmol/L) | 118 pg/mL (26 pmol/L] | 16.5 pg/mL (3.6 pmol/L) | 159 pg/mL (35 pmol/L] | 39 pg/mL (8.6 pmol/L) |

| PM cortisol 2.9-17.3 µg/dL (80-477 nmol/L) | 57.8 µg/dL (1594 nmol/L) | — | — | — | — | <0.05 µg/dL (<1.4 nmol/L) |

| 24-h UFC 1.5-18.1 µg/24 hours (4-50 nmol/24 hours) | 4223 µg/24 hours (11 656 nmol/24 hours) | 10.5 µg/24 hours (29 nmol/24 hours) | 52.9 µg/24 hours (146 nmol/24 hours) | 13 µg/24 hours (36 nmol/24 hours) | 670.5 µg/24 hours (1851 nmol/24 hours) | 23 µg/24 hours (63 nmol/24 hours) |

| Post 1-mg DST cortisol <1.8 ng/dL (<50 nmol/L) | 74.6 ng/dL (2059 nmol/L) | — | 26.9 ng/dL (743 nmol/L) | 1.4 ng/dL (<50 nmol/L) | 16.7 ng/dL (461 nmol/L) | — |

| Salivary cortisol < 0.09 µg/dL (<2.5 nmol/L) | — | 0.08 µg/dL (2.2 nmol/L) | — | 0.04 µg/dL (1.1 nmol/L) | — | — |

| S-DHEA 7-162 µg/dL (0.19-4.37 µmol/L) | — | 63 µg/dL | — | — | — | — |

| Chromogranin A <311 ng/mL* (<311 µg/L) | 725 ng/mL (30.6 nmol/L) | — | — | — | — | — |

| Lipase 8-78 U/L | 40.0 U/L (40.0 U/L) | — | — | — | — | — |

| Hemoglobin A1c <5.7% | 8.9% | 5.9% | 9.2% | 5.9% | — | — |

International System of Units are included within parentheses.

Dash (–) indicates that no data are available.

* Method dependent.

Abbreviations: ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone; AM, morning; DST, dexamethasone suppression test; EP, eucortisolemic phase; IP, initial presentation; PM, afternoon; S-DHEA, serum dehydroepiandrosterone; UFC, urine free cortisol.

Figure 1.

Table 2.

Imaging workup summary

| Case | Imaging modalities | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Case 1 | Pituitary MRI, CT chest/abdomen/pelvis, pelvic USG, 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT | No ectopic ACTH-secreting source identified |

| Case 2 | Pituitary MRI, CT chest/abdomen/pelvis, 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT | No ectopic ACTH-secreting source identified |

| Case 3 | Pituitary MRI, CT chest/abdomen/pelvis, pelvic USG, 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT | No ectopic ACTH-secreting source identified |

Abbreviations: ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone; CT, computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PET, positron emission tomography; USG, ultrasound.

Table 3.

ACTH levels from inferior petrosal sinus sampling

| Variable | −5 Minutes | 0 Minutes | +2 Minutes | +5 Minutes | +10 Minutes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CASE 1 | |||||

| Right IPS | 239 pg/mL (52.6 pmol/L) | 221 pg/mL (48.6 pmol/L) | 218 pg/mL (48.0 pmol/L) | 239 pg/mL (52.6 pmol/L) | 217 pg/mL (47.8 pmol/L) |

| Left IPS | 226 pg/mL (49.8 pmol/L) | 221 pg/mL (48.6 pmol/L) | 216 pg/mL (47.6 pmol/L) | 251 pg/mL (55.3 pmol/L) | 213 pg/mL (46.9 pmol/L) |

| Peripheral | 225 pg/mL (49.5 pmol/L) | 219 pg/mL (48.2 pmol/L) | 210 pg/mL (46.2 pmol/L) | 217 pg/mL (47.8 pmol/L) | 237 pg/mL (52.2 pmol/L) |

| Right IPS: peripheral ratio | 1.06 | 1.00 | 1.03 | 1.10 | .92 |

| Left IPS: peripheral ratio | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.02 | 1.15 | .89 |

| CASE 2 | |||||

| Right IPS | 59 pg/mL (13.0 pmol/L) | 79 pg/mL (17.4 pmol/L) | 203 pg/mL (44.7 pmol/L) | 296 pg/mL (65.2 pmol/L) | 374 pg/mL (82.3 pmol/L) |

| Left IPS | 61 pg/mL (13.4 pmol/L) | 77 pg/mL (17.0 pmol/L) | 196 pg/mL (43.2 pmol/L) | 313 pg/mL (68.9 pmol/L) | 341 pg/mL (75.1 pmol/L) |

| Peripheral | 62 pg/mL (13.7 pmol/L) | 64 pg/mL (14.1 pmol/L) | 146 pg/mL (32.2 pmol/L) | 235 pg/mL (51.8 pmol/L) | 368 pg/mL (81.0 pmol/L) |

| Right IPS: peripheral ratio | .95 | 1.23 | 1.39 | 1.26 | 1.02 |

| Left IPS: peripheral ratio | .98 | 1.20 | 1.34 | 1.33 | .93 |

| CASE 3 | |||||

| Right IPS | 119 pg/mL (26.1 pmol/L) | 121 pg/mL (26.6 pmol/L) | 380 pg/mL (83.8 pmol/L) | 581 pg/mL (128.0 pmol/L) | 232 pg/mL (51.2 pmol/L) |

| Left IPS | 124 pg/mL (27.4 pmol/L) | 133 pg/mL (29.3 pmol/L) | 358 pg/mL (78.9 pmol/L) | 568 pg/mL (125.0 pmol/L) | 262 pg/mL (57.7 pmol/L) |

| Peripheral | 113 pg/mL (24.9 pmol/L) | 111 pg/mL (24.4 pmol/L) | 322 pg/mL (70.9 pmol/L) | 527 pg/mL (116.0 pmol/L) | 178 pg/mL (39.1 pmol/L) |

| Right IPS: peripheral ratio | 1.04 | 1.09 | 1.18 | 1.10 | 1.31 |

| Left IPS: peripheral ratio | 1.10 | 1.20 | 1.13 | 1.08 | 1.48 |

International System of Units are included within parentheses.

Baseline IPS: P > 2.0; Suggests pituitary (Cushing’s disease).

Post-stim IPS: P > 3.0; Confirms pituitary ACTH source.

Abbreviations: ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone; IPS, inferior petrosal sinus.

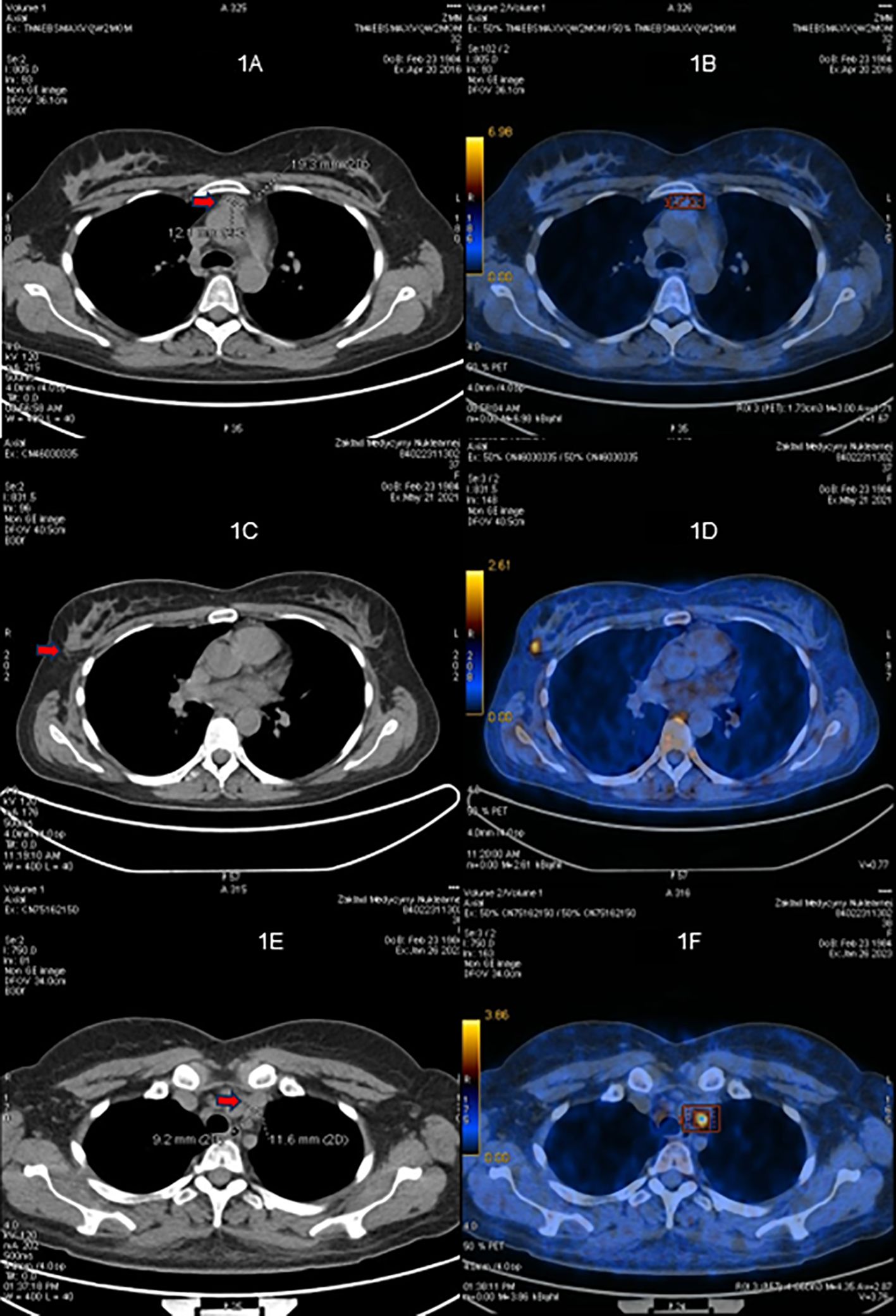

Case 2

Laboratory tests revealed elevated Am cortisol of 38.4 µg/dL (SI: 1060 nmol/L) and Am ACTH of 118 pg/mL (SI: 26 pmol/L), hypokalemia (potassium, 2.9 mEq/L [SI: 2.9 mmol/L]) and new-onset type 2 diabetes mellitus with a random blood glucose of 489 mg/dL (SI: 27.2 mmol/L) and HbA1c of 9.2% (reference range, < 5.7%) (Table 1). Lumbar spine radiography and spine MRI demonstrated compression fractures of L1 to L4 vertebrae, and pituitary MRI showed a 2-mm hypo-enhancing foci within the midline and to the right of the pituitary gland (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Case 3

During the present hospital admission, the patient was hypokalemic (potassium, 2.7 mEq/L [SI: 2.7 mmol/L]) and hypercortisolemic with Am cortisol and Am ACTH levels of 56.8 µg/dL (SI: 1568 nmol/L) and 159 pg/mL (SI: 35 pmol/L), respectively. After 4 days of hospitalization, the patient spontaneously became eucortisolemic with an Am cortisol of 16.8 µg/dL (SI: 464 nmol/L), 24-hour UFC of 670.5 µg/24 hours (SI: 1851 nmol), and late-night salivary cortisol of 0.03 µg/dL (SI: 0.828 nmol/L) with symptom improvement (Table 1). Pituitary MRI revealed a flattened, normal-appearing pituitary gland (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Treatment

Case 1

Because of the patient’s worsening clinical condition and severe hypercortisolemia with no identifiable ACTH source, ketoconazole was considered to induce eucortisolemia. While electrocardiography and liver function tests were being measured before starting ketoconazole, the patient’s Am cortisol levels spontaneously normalized to 14.2 µg/dL (SI: 392 nmol/L) with symptomatic improvement.

Case 2

The patient began insulin, spironolactone, and levothyroxine therapy. After 2 days in the hospital, her Am cortisol decreased to 17.9 µg/dL (SI: 494 nmol/L) and remained within the range of 9.4 to 17.9 µg/dL (SI: 259-494 nmol/L). An IPSS performed 3 weeks later showed no significant ACTH gradient, supporting the likelihood of an ectopic ACTH-secreting source. By month 3, her Am cortisol levels consistently remained below 15 µg/dL (SI: 414 nmol/L). Blood pressure was controlled with one antihypertensive agent, and insulin was discontinued due to frequent hypoglycemic episodes.

Case 3

The patient was readmitted 18 months later with worsening muscle weakness, uncontrolled hypertension, hypokalemia (potassium, 2.4 mEq/L [SI: 2.4 mmol/L]), and hypercortisolemia with elevated Am cortisol and Am ACTH levels. 68Ga-DOTATATE PET did not reveal an ectopic ACTH source (Table 2), and IPSS did not reveal any significant ACTH gradient (Table 3). However, computed tomography (CT) of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis revealed a 0.7-cm lung nodule. During this hospitalization, the patient received supportive treatment, including antihypertensive therapy and electrolyte replacement. No pharmacologic intervention was required to control her cortisol levels.

Outcome and Follow-Up

Case 1

Late-night salivary cortisol levels measured were within the normal range (0.08 µg/dL, 0.06 µg/dL, and 0.08 µg/dL [SI: 2.2 nmol/L, 1.7 nmol/L, and 2.2 nmol/L]; reference range, < 0.09 µg/dL [SI: < 2.5 nmol/L]). Because of these biochemical and symptomatic improvements, ketoconazole therapy was deferred. At the most recent outpatient clinic follow-up 26 months after his cortisol levels normalized, the patient remained in remission without recurrence of hypercortisolemic symptoms.

Case 2

The patient remained in biochemical and clinical remission for 15 months until she began experiencing abdominal distention, bilateral leg edema, and facial swelling again. Blood pressure increased at this time, requiring 3 antihypertensive medications. Her Am cortisol levels rose to 29.1 µg/dL (SI: 803 nmol/L), but repeat IPSS showed no ACTH gradient, and 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis was unremarkable (Tables 2 and 3). Block-and-replace therapy of osilodrostat and hydrocortisone was initiated to preemptively prevent hypercortisolemic episodes; after 3 months of therapy, she underwent successful bilateral adrenalectomy (BLA).

Case 3

On day 5 of hospitalization, her Am cortisol level decreased to 14.4 µg/dL (SI: 397 nmol/L) (reference range, 5-25 µg/dL [SI: 138-690 nmol/L]). Her symptoms improved, and she remained well for 11 months before recurrence of muscle weakness, hypokalemia, and hypercortisolemia with an Am cortisol of 58.7 µg/dL (SI: 1620 nmol/L) and Am ACTH of 194 pg/mL (SI: 43 pmol/L). The patient became eucortisolemic without any medical intervention and declined further treatment. She continues with regular outpatient follow-up.

Discussion

Diagnosing CCS poses considerable challenges because of its heterogeneous clinical manifestations, erratic intercyclic duration, frequency of phases, and various etiologies. Patients may experience transient or continuous symptoms with variable degrees of severity [1]. Our patients presented with severe hypercortisolemia lasting from days to months, followed by an extended period of spontaneous eucortisolemia, lasting from months to years. This unique presentation of cortisol kinetics differs from the classic presentation of CCS, which typically features shorter intercyclic phases [2].

We coined the term square wave variant of CCS to characterize this unique feature of prolonged cyclicity of hypercortisolemia shifting spontaneously to eucortisolemia without medical intervention. The term square wave was chosen because the cortisol secretion pattern in these cases resembles a square waveform, with abrupt transitions between prolonged periods of high and low cortisol levels rather than the gradual fluctuations or short irregular peaks seen in typical CCS. This visual and kinetic analogy helps distinguish the pattern observed in our patients from the more classically described forms of CCS.

The absence of a standardized definition of CCS complicates the classification of cases such as ours, which diverge from conventional descriptions in the medical literature [3, 4, 8]. Most cases of CCS are associated with pituitary tumors (67%), whereas ectopic ACTH-secreting tumors (17%) and adrenal tumors (11%) are less common [7, 9]. Our patients had evidence of ectopic CS, of which the ACTH-secreting source was unidentifiable despite extensive imaging. The variability of symptom duration, severity, and timing in our patients implies distinct mechanisms for suppressing or desensitizing adrenal cortisol synthesis during the extended symptom-free periods. Other mechanisms include enhanced effects of specific neurotransmitters, hypothalamic dysregulation, spontaneous tumor hemorrhage, cyclic growth and apoptosis of ACTH-secreting tumor cells, and positive and negative feedback mechanisms [7]. Another explanation for the prolonged eucortisolemic phase may be due to altered POMC gene expression and defective ACTH secretion from the ectopic tumor [10‐13]. Over time, the tumor may dedifferentiate or develop a transcriptional or posttranscriptional defect, leading to the secretion of ACTH with a decreased ability to stimulate adrenal cortisol secretion [14, 15]. Conversely, CCS might also be an exaggerated physiological cyclical variation of ACTH and cortisol secretion [14, 15]. However, the prolonged eucortisolemic phase observed in our patients argues against this exaggeration theory.

Recent studies have suggested that the anomalous cyclicity of cortisol and ACTH may be influenced by dysregulation of the peripheral clock system in endocrine tumors [16]. Certain tumors may exhibit aberrant expression of circadian regulators such as CLOCK, PER1, PER2, PER3, and TIMELESS, which can disrupt the physiological rhythmicity of cortisol and ACTH secretion [16, 17]. For instance, cortisol-secreting adrenal adenomas demonstrate downregulation of PER1, CRY1, and Rev-ERB, whereas adrenocortical carcinomas upregulate CRY1 and PER1 and downregulate BMAL1 and RORα. In patients with CS, clock gene expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells has been shown to be significantly flattened, contributing to the loss of circadian variation in cortisol levels [16].

Surgery is the preferred treatment option for CCS patients, provided the tumor is localizable [18]. Medical therapy is used when the tumor is undetectable, unresectable, or recurs. Medical therapy can overtreat and induce iatrogenic adrenal insufficiency during the eucortisolemic phases. This risk can be mitigated by the block-and-replace strategy of high-dose steroidogenesis inhibitors to suppress adrenal cortisol production and supplemented with exogenous glucocorticoids [10]. In patients for whom the ectopic tumor is unidentifiable, the initial tumor resection is ineffective, or if medical management does not adequately control hypercortisolemia, BLA may be considered [19].

Although treatment of CCS resembles that of CS, the heterogeneity in the severity and duration of symptoms prohibits the implementation of some conventional treatment strategies. Consequently, long-term medical therapy may not align with the patient’s preferences, especially those whose course of illness is characterized by prolonged eucortisolemia and milder symptoms. Such patients should be educated to monitor symptoms closely during the eucortisolemic phase to recognize the signs and symptoms of hypercortisolism using objective parameters such as self-assessment of weight, blood pressure, and capillary blood glucose. Periodic biochemical monitoring may also be helpful, including standby kits for self-testing of late-night salivary cortisol and 24-hour UFC. If the source of ectopic ACTH secretion continues to elude detection, BLA during the eucortisolemic phase may be considered to prevent future life-threatening hypercortisolemic episodes.

Learning Points

- Unlike typical CCS, there may be a subset of patients with a distinct square wave variant of CCS marked by severe hypercortisolemia followed by prolonged periods of eucortisolemia.

- Ectopic ACTH-secreting sources in CCS may be linked to unusually long symptom-free intervals of eucortisolemia and hypocortisolemia between episodes of hypercortisolemia.

- If possible, CCS management should be individualized to address its cause, with vigilant monitoring during the eucortisolemic phase to detect potential recurrence early.

- If the source of the ectopic ACTH-secreting tumor is not identifiable, BLA may be considered during the eucortisolemic phase to prevent future life-threatening hypercortisolemic episodes.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff of Neuroscience Publications at Barrow Neurological Institute for assistance with manuscript preparation.

Abbreviations

- ACTH

- adrenocorticotropic hormone

- BLA

- bilateral adrenalectomy

- CCS

- cyclic Cushing syndrome

- CS

- Cushing syndrome

- CT

- computed tomography

- HbA1c

- glycated hemoglobin

- IPSS

- inferior petrosal sinus sampling

- MRI

- magnetic resonance imaging

- PET

- positron emission tomography

- UFC

- urine free cortisol

Contributor Information

Mercedes Martinez-Gil, Department of Internal Medicine, Creighton University School of Medicine, Phoenix, AZ 85012, USA.

Tshibambe N Tshimbombu, Department of Neurology, Barrow Neurological Institute, St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center, Phoenix, AZ 85013, USA.

Yvette Li Yi Ang, Division of Endocrinology, Department of Medicine, National University Hospital, Singapore 119228, Singapore.

Monica C Rodriguez, Barrow Pituitary Center, Barrow Neurological Institute, University of Arizona College of Medicine and Creighton University School of Medicine, Phoenix, AZ 85012, USA.

Kevin C J Yuen, Barrow Pituitary Center, Barrow Neurological Institute, University of Arizona College of Medicine and Creighton University School of Medicine, Phoenix, AZ 85012, USA.

Contributors

All authors contributed substantially to the manuscript. K.C.J.Y. supervised the project, provided content review, and edited the text. M.M.-G. and T.N.T. contributed equally to the preparation, writing, and submission of the manuscript. M.C.R. was responsible for the clinical management of one of the cases. Y.L.Y.A. contributed to the diagnosis, management, and writing of one of the cases. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

All authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could appear to influence the work reported in this manuscript.

Disclosures

The authors have no personal, financial, or institutional interest in any of the drugs, materials, or devices described in this manuscript.

Informed Patient Consent for Publication

Signed informed consents were obtained directly from the patients.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

- 1. Swiatkowska-Stodulska R, Berlinska A, Stefanska K, Klosowski P, Sworczak K. Cyclic Cushing’s syndrome—a diagnostic challenge. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12:658429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Shapiro MS, Shenkman L. Variable hormonogenesis in Cushing’s syndrome. Q J Med. 1991;79(288):351‐363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Alexandraki KI, Kaltsas GA, Isidori AM, et al. The prevalence and characteristic features of cyclicity and variability in Cushing’s disease. Eur J Endocrinol. 2009;160(6):1011‐1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Meinardi JR, Wolffenbuttel BH, Dullaart RP. Cyclic Cushing’s syndrome: a clinical challenge. Eur J Endocrinol. 2007;157(3):245‐254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McCance DR, Gordon DS, Fannin TF, et al. Assessment of endocrine function after transsphenoidal surgery for Cushing’s disease. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1993;38(1):79‐86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jahandideh D, Swearingen B, Nachtigall LB, Klibanski A, Biller BMK, Tritos NA. Characterization of cyclic Cushing’s disease using late night salivary cortisol testing. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2018;89(3):336‐345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nowak E, Vogel F, Albani A, et al. Diagnostic challenges in cyclic Cushing’s syndrome: a systematic review. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2023;11(8):593‐606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Brown RD, Van Loon GR, Orth DN, Liddle GW. Cushing’s disease with periodic hormonogenesis: one explanation for paradoxical response to dexamethasone. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1973;36(3):445‐451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sederberg-Olsen P, Binder C, Kehlet H, Neville AM, Nielsen LM. Episodic variation in plasma corticosteroids in subjects with Cushing’s syndrome of differing etiology. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1973;36(5):906‐910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cai Y, Ren L, Tan S, et al. Mechanism, diagnosis, and treatment of cyclic Cushing’s syndrome: a review. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022;153:113301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Coates PJ, Doniach I, Howlett TA, Rees LH, Besser GM. Immunocytochemical study of 18 tumours causing ectopic Cushing’s syndrome. J Clin Pathol. 1986;39(9):955‐960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. de Keyzer Y, Bertagna X, Lenne F, Girard F, Luton JP, Kahn A. Altered proopiomelanocortin gene expression in adrenocorticotropin-producing nonpituitary tumors. Comparative studies with corticotropic adenomas and normal pituitaries. J Clin Invest. 1985;76(5):1892‐1898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Oliver RL, Davis JR, White A. Characterisation of ACTH related peptides in ectopic Cushing’s syndrome. Pituitary. 2003;6(3):119‐126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Atkinson AB, Chestnutt A, Crothers E, et al. Cyclical Cushing’s disease: two distinct rhythms in a patient with a basophil adenoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1985;60(2):328‐332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Atkinson AB, Kennedy AL, Carson DJ, Hadden DR, Weaver JA, Sheridan B. Five cases of cyclical Cushing’s syndrome. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1985;291(6507):1453‐1457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Angelousi A, Nasiri-Ansari N, Karapanagioti A, et al. Expression of clock-related genes in benign and malignant adrenal tumors. Endocrine. 2020;68(3):650‐659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hasenmajer V, Sbardella E, Sciarra F, et al. Circadian clock disruption impairs immune oscillation in chronic endogenous hypercortisolism: a multi-level analysis from a multicentre clinical trial. EBioMedicine. 2024;110:105462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nieman LK, Biller BM, Findling JW, et al. Treatment of Cushing’s syndrome: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(8):2807‐2831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bertherat J. Cushing’s disease: role of bilateral adrenalectomy. Pituitary. 2022;25(5):743‐745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Filed under: Cushing's, Rare Diseases, symptoms | Tagged: Cyclical Cushing's, Ectopic Cushing’s syndrome, eucortisolemia, hypercortisolemia, NIH | Leave a comment »