Abstract

Objective

Cushing’s syndrome is characterized by high morbidity and mortality with high interindividual variability. Easily measurable biomarkers, in addition to the hormone assays currently used for diagnosis, could reflect the individual biological impact of glucocorticoids. The aim of this study is to identify such biomarkers through the analysis of whole blood transcriptome.

Design

Whole blood transcriptome was evaluated in 57 samples from patients with overt Cushing’s syndrome, mild Cushing’s syndrome, eucortisolism, and adrenal insufficiency. Samples were randomly split into a training cohort to set up a Cushing’s transcriptomic signature and a validation cohort to assess this signature.

Methods

Total RNA was obtained from whole blood samples and sequenced on a NovaSeq 6000 System (Illumina). Both unsupervised (principal component analysis) and supervised (Limma) methods were used to explore the transcriptome profile. Ridge regression was used to build a Cushing’s transcriptome predictor.

Results

The transcriptomic profile discriminated samples with overt Cushing’s syndrome. Genes mostly associated with overt Cushing’s syndrome were enriched in pathways related to immunity, particularly neutrophil activation. A prediction model of 1500 genes built on the training cohort demonstrated its discriminating value in the validation cohort (accuracy .82) and remained significant in a multivariate model including the neutrophil proportion (P = .002). Expression of FKBP5, a single gene both overexpressed in Cushing’s syndrome and implied in the glucocorticoid receptor signaling, could also predict Cushing’s syndrome (accuracy .76).

Conclusions

Whole blood transcriptome reflects the circulating levels of glucocorticoids. FKBP5 expression could be a nonhormonal marker of Cushing’s syndrome.

In Cushing’s syndrome, specific hormone assays inform about the level of deviation from normal range. The blood transcriptome signature proposed here is also able to discriminate patients, without any hormone measurements. This direct measurement of the biological impact of glucocorticoids at a tissue level may better reflect the individual consequences of glucocorticoid excess.

Introduction

Cushing’s syndrome (CS) is a condition characterized by chronic cortisol excess related to glucocorticoid treatment (exogenous Cushing’s syndrome) or to endogenous hypercortisolism. The excessive cortisol secretion may be due to either adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)–dependent conditions, most often an ACTH-producing pituitary adenoma (Cushing’s disease), or ACTH-independent causes, commonly a benign adrenal adenoma.1 Chronic exposure to glucocorticoid excess results in specific complications, including cardiovascular and thromboembolic diseases, diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome, osteoporosis, and neurocognitive disorders. Numerous comorbidities result in impaired quality of life and increased mortality.2-4

Despite the availability of different hormonal tests for diagnosis and follow-up, the clinical management of these patients remains challenging, since none of the available tools proved to be fully accurate due to the variable pattern of cortisol secretion and the pitfalls of the hormonal immunoassays.5,6 Moreover, the clinical effects of glucocorticoid exposure on peripheral tissues depend not only on the intensity and duration of glucocorticoid excess but also on the peripheral glucocorticoid metabolism and the individual sensitivity to glucocorticoids, not accurately estimated by hormonal parameters. This results in the high interindividual variability frequently reported in Cushing’s syndrome.7,8 Recent studies suggested that the combined assessment of cortisol secretion, cortisone-to-cortisol peripheral activation by the 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase enzyme, and glucocorticoid receptor sensitizing variants may better estimate the risk to develop each type of complications.9-11

These aspects are crucial mainly for the management of patients with mild Cushing’s syndrome, not clearly characterized by classical features of cortisol excess but consistently associated to an increased risk of morbidities and mortality.12,13 Mild hypercortisolism can occur in different settings. In patients with adrenal incidentalomas, mild hypercortisolism is currently referred to as mild autonomous cortisol secretion (MACS).14 In patients with Cushing’s disease, mild hypercortisolism occurs when hypercortisolism persists/recurs after pituitary surgery or under medical treatment.12,15,16 Irrespective of the origin of cortisol excess, it is still debated whether patients with mild hypercortisolism, as well as those under low-dose systemic or local glucocorticoid therapy, need a close follow-up for cortisol excess–related complications and specific preventive treatments.17-19

In this context, genomic-based studies have recently focused on the identification of blood molecular markers in patients exposed to glucocorticoid excess, aiming to a better individual characterization of these patients. Particularly, DNA methylation profile has been investigated as a potential biological hallmark of glucocorticoid action. Previous studies suggested an association between hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis dysregulation and specific blood DNA methylation profiles, particularly in post-traumatic stress disorders, while recently a dynamic whole blood DNA methylation signature reflecting glucocorticoid excess has been identified.20-22 In both genomic-based and preclinical studies, FKBP5, a gene implicated in glucocorticoid signaling, emerged as potential non hormonal marker of glucocorticoid excess.22-24

The present study completes the previous approaches exploring the impact of glucocorticoids on whole blood transcriptome to better understand the molecular mechanisms of glucocorticoid impregnation. Specifically, through the analysis of whole blood transcriptome profiles from patients with endogenous Cushing’s syndrome, eucortisolism, or adrenal insufficiency, we proposed a transcriptome signature predicting glucocorticoid excess.

Materials and methods

Patients and samples

Fifty-seven blood samples were collected from 43 patients with a confirmed diagnosis of endogenous Cushing’s syndrome, followed in Cochin Hospital (APHP, Paris, France). Diagnostic criteria of Cushing’s syndrome included increased 24-h urinary free cortisol, abnormal cortisol after 1 mg dexamethasone suppression, and altered circadian cortisol rhythm, following consensus guidelines.25

For 14 patients, blood samples were collected before correction of Cushing’s syndrome and at least 3 months after Cushing’s syndrome treatment. At the time of blood sampling, patients were classified as overt Cushing’s syndrome, mild Cushing’s syndrome, eucortisolism, or adrenal insufficiency, depending on clinical and hormonal evaluation. Briefly, overt Cushing’s syndrome patients presented clinical signs and increased 24-h urinary free cortisol (>240 nmol/24 h), increased midnight salivary cortisol (>6 nmol/L), and insufficient cortisol suppression after 1 mg dexamethasone (>50 nmol/L). The mild Cushing’s syndrome cohort included patients with mild hypercortisolism due to either Cushing’s disease or benign adrenal Cushing’s syndrome. The former were patients with persistent or recurrent hypercortisolism after pituitary surgery or during medical treatment; in these patients, the diagnosis of Cushing’s disease was confirmed by the histopathological report consistent with a corticotroph adenoma in the surgically treated patients (6 out of 7) and by the magnetic resonance imaging evidence of a pituitary adenoma in the upfront medically treated patient. Mild hypercortisolism in patients with Cushing’s disease was defined, as previously reported,16,26 by the absence of clinically overt signs of CS and a slight alteration in cortisol secretion, including either increased 24-h urinary free cortisol or increased midnight cortisol or inadequate cortisol suppression after 1 mg of dexamethasone. For mild hypercortisolism due to benign adrenal CS, MACS criteria were used—post-dexamethasone serum cortisol concentration above 50 nmol/L—following recent consensus guidelines.14 The term “mild” was retained for 1 patient with benign adrenal CS who had a borderline dexamethasone suppression test (48 nmol/L) but increased 24-h urinary free cortisol. Eucortisolism was defined as a combination of normalized 24-h urinary free cortisol and of restored cortisol circadian rhythm after either surgery or medical treatment. Adrenal insufficiency was secondary to pituitary surgery for Cushing’s disease. The diagnosis was based on low morning plasma cortisol (<160 nmol/L) and confirmed by the insufficient response to 250 µg corticotropin stimulation test (<500 nmol/L), following the current consensus guidelines.27,28 Detailed hormone values for each sample are provided in Table S1.

Thirty additional samples were collected from patients followed in Hôpital Européen Georges Pompidou Hospital (APHP, Paris, France). These patients presented pheochromocytoma (n = 19) and primary hyperaldosteronism (n = 11; Table S1). The diagnosis was made following the consensus guidelines.29,30

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Signed informed consent for molecular analysis of blood samples and for access to clinical data was obtained from all patients, and the study was approved by the institutional review board (Comité de Protection de Personnes Ile de France 1, projects 13495 and 13311).

RNA collection and extraction

Whole blood samples were collected into PAXgene Blood RNA Tube (PreAnalytiX, Hombrechtikon, Switzerland), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Total RNA was extracted by using PAXgene Blood RNA Kit, v2 (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Transcriptome data generation

After RNA extraction, RNA concentrations were obtained using nanodrop or a fluorometric Qubit RNA assay (Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA). The quality of the RNA (RNA integrity number, RIN) was determined on the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA) following manufacturer’s instructions.

To construct the libraries, 250 ng of high-quality total RNA sample (RIN > 8) was processed using the Stranded mRNA Prep kit (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, after purification of poly-A–containing mRNA molecules, mRNA molecules were fragmented and reverse-transcribed using random primers. Replacement of dTTP (deoxythymidine triphosphate) by dUTP (deoxyuridine triphosphate) during the second-strand synthesis permitted to achieve the strand specificity. Addition of a single A base to the cDNA was followed by ligation of Illumina adapters. Libraries were quantified on a Qubit fluorometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), and profiles were assessed using the DNA High Sensitivity LabChip kit on an Agilent Bioanalyzer (Agilent Technologies). Libraries were sequenced on a NovaSeq 6000 System (Illumina), using 51 base-lengths read in a paired-end mode.

Whole blood methylome data

Among the 57 samples included in the transcriptome analysis, 32 were also used for a methylome analysis recently published.22 For each gene, potentially methylated cytosines-referred to as CpGs- in the promoter regions were defined as CpGs belonging to the TSS1500, TSS200, 5′UTR, and first exon regions. CpG methylation levels were analyzed using M-values generated as previously reported.22

Bioinformatics and statistics

Quality control was performed on raw count matrix, with a target of >5 million reads per sample. All samples passed this control. Illumina adapters were removed using Trimmomatic (v0.39) in paired-end mode.31 Reads were aligned to the reference human genome (GRCh37) and counted using STAR (v2.7.9a).32 Counts were aggregated for transcripts corresponding to the same gene, and only genes with a count sum > 0 in all samples were further considered. Globin genes and sex-related genes were also discarded, as previously published.33

Counts were normalized with DESeq2, using rlog transformation34 (v.1.24.0): raw counts were converted to distributed data structures (dds), and lowly expressed genes were removed using a dds > 1 in at least 3 samples as cutoff, obtaining a final dataset of n = 21 116 and n = 57 samples. The 1500 most variable genes were selected to assess the global data structure by principal component analysis (PCA). Overrepresentation analysis of genes most contributing to PCA components was performed using clusterProfiler package35 (v.3.12.0).

From gene counts, blood cell composition was inferred using the online CIBERSORTx tool (Stanford University 2022),36 with the following parameters: B-mode batch correction, disabled quantile normalization, absolute mode, and n = 500 permutations. For each cell types, a score was generated, reflecting the absolute proportion of each cell type in a mixture.

For supervised differential expression analysis, the edgeR package37 (v.3.26.8) was used to read and preprocess the data before analysis: raw counts were converted to counts per million (CPM), and lowly expressed genes were removed using a CPM > 1 in at least 3 samples as cutoff. To remove heteroscedascity of count data, normalized data were transformed using the voom function.38 Differential expression analysis was performed by applying linear modeling using the limma package39 (v. 3.40.6). Differentially expressed genes were selected using a Benjamin–Hochberg adjusted P < .05 and a logFC > 1 as cutoffs. Overrepresentation analysis of differentially expressed genes was performed using the clusterProfiler package. Of note, the edgeR normalization did not significantly modify the normalized expression levels compared to DESeq2 (gene expression correlation r = .9924, P < 2.2e−16).

For predicting glucocorticoid status from transcriptome, we carried out a Ridge-regularized regression (α = 0) using the 1500 most variable genes, with a 4-fold cross-validation, using the glmnet package40 (v. 4.1-1). The optimization of the 1500 gene predictor was performed on a training cohort of 29 samples, randomly selected from the whole cohort and including 18 samples corresponding to overt Cushing’s syndrome and 11 samples corresponding to either eucortisolism or adrenal insufficiency (patients with mild Cushing’s syndrome were excluded). The accuracy of the 1500 gene predictor was assessed on 2 validation cohorts: a first one (n = 17) including overt Cushing’s syndrome, eucortisolism, and adrenal insufficiency samples, and a second one (n = 30) including pheochromocytoma and primary hyperaldosteronism samples. The latter cohort was used to test the specificity of the predictor, given the different nature of catecholamine excess and primary hyperaldosteronism from Cushing’s syndrome.

Quantitative variable comparisons between groups were performed using Student’s t-test for variables following a normal distribution, or Wilcoxon’s test and Kruskal–Wallis test for variables not following a normal distribution. Quantitative variable correlations were performed using Pearson’s or Spearman’s test according to data distribution. Multivariate logistic regression model including the 1500 gene transcriptome predictor and the neutrophil score was used to test the association with glucocorticoid status. All P-values were 2-sided, and the level of significance was set at .05. All tests were computed in R software environment (3.6.0 version).

Results

Cohort presentation

Fifty-seven blood samples were collected from 43 patients (Table 1; Table S1). Samples were collected at different time points during the disease, thus reflecting different glucocorticoid status: overt Cushing’s syndrome (n = 28), mild Cushing’s syndrome (n = 11), eucortisolism (n = 10), and adrenal insufficiency (n = 8).

Table 1.

Overall cohort presentation and group comparisons.

| Glucocorticoid status |

|

Whole cohort

median (IQR) |

Training cohort

median (IQR) |

First validation cohort

median (IQR) |

P-valuea |

| Samples |

Total |

57 |

29 |

17 |

|

| Overt Cushing’s syndrome |

N |

28 |

18 |

10 |

|

Urinary free cortisol

nmol/24 h (<240) |

879.5

(419) |

879.5

(307.5) |

904.5

(5469.25) |

.688 |

Midnight salivary cortisol

nmol/L (<6) |

14

(12) |

11

(8.5) |

17.5

(27.5) |

.034 |

Plasma cortisol after 1 mg DST

nmol/L (<50) |

232

(288) |

218

(271) |

232

(460) |

.419 |

| Mild Cushing’s syndrome |

N |

11 |

NA |

NA |

NA |

Urinary free cortisol

nmol/24 h (<240) |

273

(100) |

NA |

NA |

NA |

Midnight salivary cortisol

nmol/L (<6) |

7

(5.5) |

NA |

NA |

NA |

Plasma cortisol after 1 mg DST

nmol/L (<50) |

56

(19.75) |

NA |

NA |

NA |

| Eucortisolism |

N |

10 |

6 |

4 |

|

Urinary free cortisol

nmol/24 h (<240) |

183

(87.75) |

159

(71.25) |

204

(39.25) |

.521 |

Midnight salivary cortisol

nmol/L (<6) |

4

(1) |

4

(0) |

4.5

(1.25) |

.797 |

| Plasma cortisol after 1 mg DST nmol/L (<50) |

35

(11) |

31

(8.5) |

41.5

(6.5) |

.4 |

| Adrenal insufficiency |

N |

8 |

5 |

3 |

|

| Early morning plasma cortisol nmol/L (160–500) |

95.5

(66.75) |

95.5

(28.25) |

98

(98) |

1 |

| Cortisol after ACTH stimulation nmol/L (<500) |

405.5

(165.25) |

435.5

(128.75) |

308

(163) |

.142 |

Cortisol values are provided as median values with interquartile range (IQR). aWilcoxon’s test comparing training and first validation cohorts.

Median age was 48 years (range: 26 to 73), with a female predominance (2.35 to 1). Cushing’s syndrome corresponded either to Cushing’s disease (n = 26) or to benign adrenal Cushing’s syndrome (n = 17). Mild Cushing’s syndrome cohort included 7 patients with Cushing’s disease and 4 patients with a benign adrenal tumor. Hypercortisolism-related complications, including hypertension, diabetes, and osteoporosis, were present in 41 (71.9%), 16 (28.0%), and 10 (17.5%) patients, respectively.

For the purpose of building and evaluating a glucocorticoid status predictor from blood transcriptome, we focused on patients with overt Cushing’s syndrome, eucortisolism, and adrenal insufficiency, excluding patients with mild Cushing’s syndrome (n = 11) due to their uncertain glucocorticoid status. Patients were randomly assigned either to a training (n = 29) or to a first validation cohort (n = 17). A second validation cohort of 30 samples was used to test the specificity of the predictor, including 19 patients with pheochromocytoma and 11 patients with primary hyperaldosteronism (Table S1).

Impact of glucocorticoid level on whole blood transcriptome

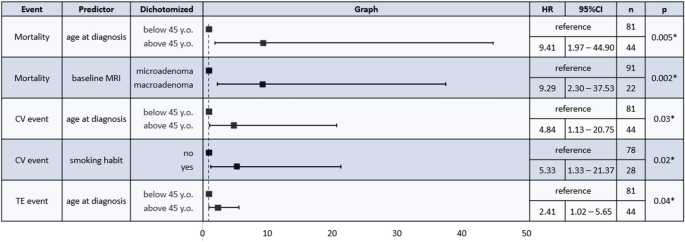

Unsupervised PCA on the 1500 most variable genes of the whole cohort (samples = 57) discriminated patients according to their glucocorticoid status (Figure 1A). This discrimination was mainly based on the first principal component (PC1; Table S2). In terms of gene expression signature, PC1 was enriched in signaling pathways related to immune response, particularly those relative to neutrophils’ activation and degranulation (Figure 1B; Table S3). Beyond the immune response, PC1 was also enriched in genes more generally involved in the response to glucocorticoids,41 including FKBP5, PBX1, SPI1, CDK5R1, CXCL8, NR4A1, and TBX21 (Table S2).

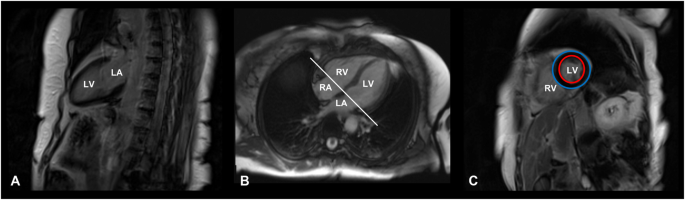

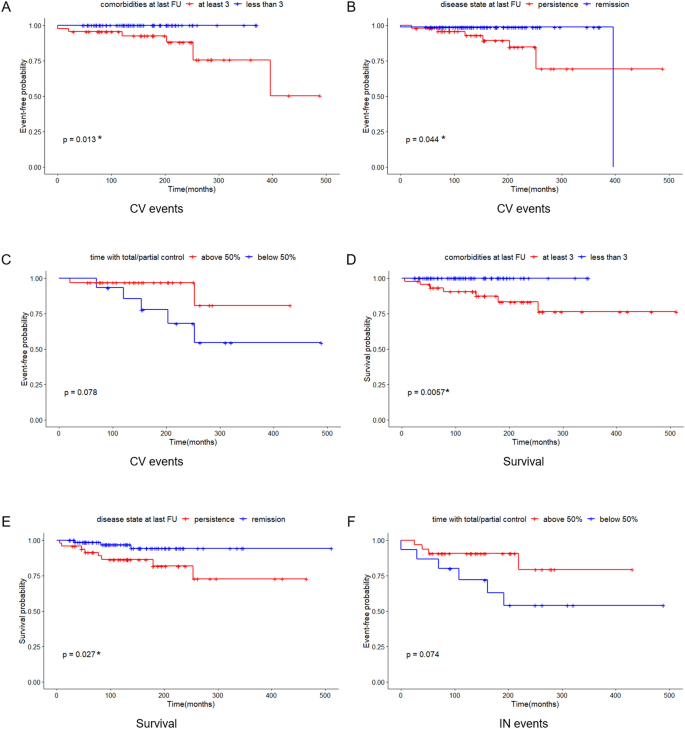

Figure 1.

Impact of glucocorticoid levels on whole blood transcriptome. (A) Sample projections based on the combination of the first 2 principal components (PC1 and PC2) of unsupervised PCA performed on the 1500 most variable genes of the whole cohort (n = 57). (B) Dot plot of the 10 most GO-enriched signaling pathways in overt Cushing’s syndrome, using the PC1 coefficients.

Accordingly, a supervised comparison of Cushing’s syndrome samples (n = 28) against eucortisolism/adrenal insufficiency samples (n = 18) provided similar results (Figure 2; Table S4).

Figure 2.

Differentially expressed genes in overt Cushing’s syndrome. Volcano plot of the differentially expressed genes (n = 517) in overt Cushing’s syndrome (n = 28) versus eucortisolism/adrenal insufficiency (n = 18).

Predicting glucocorticoid status by blood transcriptome

To predict glucocorticoid status by whole blood transcriptome, we performed a cross-validated Ridge-regularized regression, using the 1500 most variable genes. The 1500 transcriptome predictor was optimized in the training cohort to discriminate overt Cushing’s syndrome from eucortisolism/adrenal insufficiency (Table S5). The predictive value of this model was confirmed on both the first and the second validation cohorts (accuracy of .82 and 1, respectively, Table 2; Table S6). Accordingly, samples from the second validation cohort clustered with eucortisolism/adrenal insufficiency samples, as assessed by PCA (Figure S1).

Table 2.

Performance of molecular predictors, based on the whole blood transcriptome signature and on FKBP5 expression level, in discriminating glucocorticoid excess.

| Cohort |

Predictor |

Accuracy |

Sensitivity |

Specificity |

| First validation cohort |

Predictor based on 1500 genes |

.82 |

.90 |

.85 |

| Predictor based on FKBP5 |

.76 |

.80 |

.71 |

| Second validation cohort |

Predictor based on 1500 genes |

1 |

NAa |

1 |

| Predictor based on FKBP5 |

.46 |

NAa |

.46 |

aNot applicable due to the lack of true positives in the second validation cohort.

Mild Cushing’s syndrome samples—excluded from the training and validation cohorts—were classified either as overt Cushing’s syndrome (n = 5/11, 45.5%) or as eucortisolism/adrenal insufficiency (n = 6/11, 54.5%). Of note, the Ridge scores for samples classified as overt Cushing’s syndrome in the mild Cushing’s syndrome cohort was lower than in the training and the first validation cohorts (Wilcoxon, P = .008). The Ridge scores for samples classified as eucortisolism/adrenal insufficiency in the mild Cushing’s syndrome cohort did not differ from the training and first validation cohorts (Wilcoxon, P = .9; Table S6). Accordingly, mild Cushing’s syndrome samples were projected in-between overt Cushing’s syndrome and eucortisolism samples on PCA (Figure 1A).

We then tested whether the glucocorticoid status could be predicted using a single gene. We focused on FKBP5, due to (1) its Ridge regression coefficient being among the highest (Table S5), (2) its potential ability to discriminate Cushing’s syndrome,22,23 and (3) its known implication in glucocorticoid signaling (Figure 3A).42 The prediction accuracy of FKBP5 expression was comparable to the 1500 gene transcriptome predictor in the first validation cohort (accuracy: .76), but lower in the second validation cohort (accuracy: .46; Table 2; Table S7). The other genes involved in the glucocorticoid response found enriched in PC1 were not further analyzed as potential single biomarkers, since their association with Cushing’s syndrome was not confirmed in supervised analysis, and since their Ridge regression coefficients were lower than FKBP5 coefficient (Table S5).

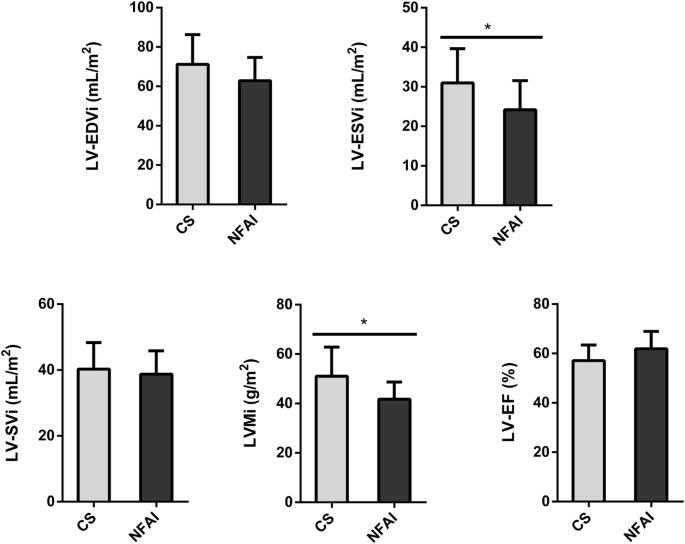

Figure 3.

FKBP5 expression related to the different glucocorticoid status. (A) Boxplot of FKBP5 gene expression in the different study groups. *Student’s t-test P < .001. (B) Representation of the positive correlation between the 24-h urinary free cortisol and FKBP5 expression (r = .72, P = 2.032e−10). (C) Representation of the inverse correlation between FKBP5 expression and the mean methylation level (M-value) of FKBP5 promoter–associated CpG site (r = −.86, P = 1.312e−10).

We then tested the contribution of blood cell composition in the 1500 gene transcriptome predictor. We inferred the different blood cell subtype proportions from the whole blood transcriptome of each sample. An expected increase of neutrophil proportion in overt Cushing’s syndrome43,44 was observed (Kruskal–Wallis’s test, P = 8.5e−06; Table S1 and Figure S2). In a multivariate model combining the 1500 gene transcriptome predictor and the neutrophil score, the 1500 gene transcriptome predictor remained significant (P = .002; Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariate model combining the 1500 gene transcriptome predictor and neutrophil scores.

| Variables |

OR |

95% CI |

P-value |

| 1500-genes predictor |

4.37 |

2.06–15.3 |

.002 |

| Neutrophils score |

.48 |

.02–6.13 |

.6 |

Training and first validation cohorts were combined. Two statuses were considered: overt Cushing’s syndrome and eucortisolism/adrenal insufficiency.

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidential Interval.

Association between blood transcriptome and Cushing’s syndrome complications

The 1500 gene transcriptome predictor was positively correlated to the 24-h urinary free cortisol (r = .78, P = 2.993e−13; Figure S3). The 1500 gene transcriptome predictor was higher in patients with osteoporosis (Wilcoxon, P = 2.9e−05), while the 24-h urinary free cortisol did not show any difference (Wilcoxon, P-value of .17, Figure 4A and B). No difference was observed between patients with and without diabetes (Wilcoxon, P = .31), nor with or without hypertension (Wilcoxon, P = .25), and the 1500 gene transcriptome predictor was not correlated to body mass index (BMI) (P-value = .108).

Figure 4.

Potential markers of osteoporosis in overt Cushing’s syndrome. Association between osteoporosis and 24-h urinary free cortisol (A), 1500 gene transcriptome predictor (B), and FKBP5 expression (C). For 24-h urinary free cortisol, values are expressed as log10.

Similar findings were obtained with FKBP5 expression level, including a positive correlation with the 24-h urinary free cortisol (r = .72, P = 2.032e−10, Figure 3B), a higher expression in patients with osteoporosis (Wilcoxon, P = 2.9e−05; Figure 4C), no difference in patients with diabetes (Wilcoxon, P = .72) or hypertension (Wilcoxon, P = .4), and no correlation with BMI (P = .657).

Association of whole blood transcriptome with whole blood methylome

For 32 samples with both whole blood transcriptome and methylome22 available (n = 32), a correlation analysis was performed. A majority of genes differentially expressed in overt Cushing’s syndrome showed a negative correlation with CpG sites of their promoter regions (Table S8). FKBP5 was among the genes showing the strongest inverse correlation (r = − .86, P adjusted = 5.94e−09; Figure 3C).

Discussion

In this study, we identified a whole blood transcriptome signature predicting the glucocorticoid excess. This signature, in addition to the hormone assays currently used for diagnosis, could reflect the individual biological impact of glucocorticoids.

We designed a predictor with optimal selection of transcriptome biomarkers able to differentiate overt Cushing’s syndrome from eucortisolism and adrenal insufficiency. The predictive value of such transcriptome predictor was confirmed on 2 validation cohorts. For patients with mild Cushing’s syndrome, our predictor showed intermediate classification, confirming the clinical heterogeneity of this group. Indeed, these intermediate patients indisputably fall in-between patients with overt Cushing’s syndrome and eucortisolism, with some overlap in both groups. Whether such non hormonal biomarkers, directly measuring glucocorticoid action, can be useful for the specific management of these patients remains to be established. The question is important, considering the high prevalence of mild Cushing’s syndrome in the general population and the still-ongoing debate on complications’ surveillance and treatment of choice.45 Here, a proper evaluation of mild Cushing’s syndrome is difficult, due to both the lack of a clear clinical definition and to the size of the cohort, not large enough to assess the existence of a specific signature for these patients, thus representing a limitation of this study. Another open question is whether the markers presented here would have comparable relevance in patients with exogenous Cushing’s syndrome, related to glucocorticoid treatments, especially for the common situation of long-term treatment with low glucocorticoid doses or with “local” glucocorticoid treatments.

Noteworthy, this identified signature derives from whole blood, a mixture of various cell types with potentially cell-dependent impact of glucocorticoids on transcriptome profile. Indeed, glucocorticoids have a direct effect on white blood cell count inducing an increase in the neutrophil proportion.43,44 We inferred white blood cell count from transcriptome profile for each sample, and, as expected, overt Cushing’s syndrome samples were characterized by higher neutrophil score, and, accordingly, genes differentially expressed in this group were enriched in immunity-related pathways, mainly in the activation and degranulation of neutrophils. However, among the genes differentially expressed in overt Cushing’s syndrome, we also identified genes more specifically involved in glucocorticoid response, suggesting differences not only related to immunity. Moreover, we demonstrated that the prediction based on transcriptome signature remained significant after adjustment for neutrophil score and therefore that transcriptome profile does not only reflect blood composition variations.

Whole blood transcriptome analysis is not easily reproducible in clinical practice. Thus, we tried to simplify the marker by focusing on one single gene. FKBP5, as a potential surrogate of the 1500 gene transcriptome signature, was able to differentiate and predict Cushing’s syndrome with a good accuracy. FKBP5 (FK506-binding protein 51) is a co-chaperone of heat shock protein 90 (Hsp90) involved in the regulation of the glucocorticoid receptor activity, maintaining it unbound and inactive in the cytoplasm, thus restricting the nuclear translocation of the cortisol receptor complex.24,46 According to preclinical studies, in the presence of glucocorticoid excess, FKBP5 expression increases at both mRNA and protein levels as an effect of intracellular negative feedback.47 Previous studies also showed that FKBP5 expression is sensitive to exogenous glucocorticoids in healthy volunteers and that FKBP5 levels are higher in patients with Cushing’s syndrome, while decreasing to normal baseline levels after successful surgery.23 It has been also demonstrated that the methylation of FKBP5 is affected by stress and dynamically by glucocorticoid level in patients with endogenous Cushing’s syndrome.42 Of note, in our second validation cohort, including patients with pheochromocytoma and primary aldosteronism, the ability of FKBP5 expression level to properly call the absence of Cushing’s syndrome dropped compared to the first validation cohort, raising concerns about potential limits in specificity. These results also highlight the importance of using larger validation cohorts with a wide variety of conditions before using such a biomarker in routine.

Interestingly, in patients with overt Cushing’s syndrome, beyond the correlation between gene expression and 24-h urinary free cortisol, the variability of gene expression was higher in patients with moderate increase of 24-h urinary free cortisol. This suggests a potential informative role of gene expression markers in patients with moderate cortisol increase. In this line, Guarnotta et al. showed that the level of urinary hypercortisolism does not seem to correlate with Cushing’s syndrome severity and that clinical features and cortisol excess–related comorbidities are more reliable indicators in the assessment of disease severity.48 In our study, the transcriptomic profile could discriminate Cushing’s syndrome patients with and without osteoporosis, although the 24-h urinary free cortisol values did not differ between the two groups. However, these results need additional validation, due to the limited cohort size and because of potential confounders not considered, including pre-existing diagnosis of osteoporosis and other determinants of skeletal fragility. Although this preliminary finding further supports the potential value of gene expression markers in predicting catabolic complications, to which extent these biomarkers are relevant in clinical practice remains to be established and better explored in larger cohorts of patients with moderate Cushing’s syndrome.

The transcriptome profile identified in this study also confirmed the previous findings obtained by analyzing the whole blood methylome in Cushing’s syndrome. The negative correlation between promoter methylation and gene expression strengthens our results and underlines the importance of epigenetic alterations in Cushing’s syndrome.49

In conclusion, we showed that the whole blood transcriptome reflects the circulating levels of glucocorticoids and that FKBP5 expression level could be a single gene non hormonal marker of Cushing’s syndrome.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Genomic platform and the team “Genomic and Signaling of Endocrine Tumors” of Institut Cochin, the French COMETE research network, the European Network for the Study of Adrenal Tumor (ENSAT), and the European Reference Network on Rare Endocrine Conditions (Endo-ERN).

Supplementary material

Supplementary material is available at European Journal of Endocrinology online.

Funding

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research and Innovation program under grant agreement no. 633983 and the Programme Hospitalier de Recherche Clinique “CompliCushing” (PHRC AOM 12-002-0064). This work was also supported by the Programme de Recherche Translationnelle en Cancérologie to the COMETE network (PRT-K COMETE-TACTIC).

Authors’ contribution

Maria Francesca Birtolo (Data curation [equal], Formal analysis [equal], Writing—original draft [equal]), Roberta Armignacco (Conceptualization [equal], Data curation [equal], Formal analysis [equal], Writing—review & editing [equal]), Nesrine Benanteur (Formal analysis [equal]), Bertrand Baussart (Writing—review & editing [equal]), Chiara Villa (Writing—review & editing [equal]), Daniel De Murat (Formal analysis [equal]), Laurence Guignat (Writing—review & editing [equal]), Lionel Groussin (Writing—review & editing [equal]), Rosella Libé (Writing—review & editing [equal]), Maria-Christina Zennaro (Data curation [equal], Writing—review & editing [equal]), Meriama Saidi (Data curation [equal]), Karine Perlemoine (Data curation [equal]), Franck Letourneur (Data curation [equal]), Laurence Amar (Data curation [equal], Writing—review & editing [equal]), Jérôme Bertherat (Writing—review & editing [equal]), Anne Jouinot (Conceptualization [equal], Formal analysis [equal], Writing—original draft [equal]), and Guillaume Assié (Conceptualization [equal], Formal analysis [equal], Funding acquisition [equal], Project administration [equal], Writing—original draft [equal]).

Data availability

Transcriptome data generated and analyzed in this study are available in the EMBL-EBI BioStudies repository (reference number: S-BSST1241).

Author notes

Conflict of interest: G.A. is on the editorial board of EJE. G.A. was not involved in the review or editorial process for this paper, on which he is listed as an author.

© The Author(s) 2024. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of European Society of Endocrinology.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted reuse, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.