Cushing’s syndrome is associated with excessive cortisol production and, if left untreated, can result in severe complications, such as heart attacks, strokes, and type 2 diabetes. To diagnose this condition, a dexamethasone suppression test is commonly performed.

Various factors, such as metabolic rate and interactions with other medications, can affect test efficacy. Therefore, it is crucial to measure the concentration of dexamethasone concurrently with cortisol to avoid false-positive results.

To address this issue, a team of researchers at the University of Turin, led by Professor Giulio Mengozzi in the Department of Medical Sciences, has developed a liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry method.

This new method enables the simultaneous quantification of cortisol, cortisone, dexamethasone, and six additional exogenous corticosteroids, leading to a more accurate diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome.

The symptoms of Cushing’s syndrome

Cushing’s syndrome is a medical condition characterized by an abnormal and prolonged increase in cortisol production, typically affecting females between the ages of 30 and 50.1

While the issue may originate from within the body (endogenous), it is more commonly caused by external factors, such as the use of glucocorticoid medications.

Visible symptoms of Cushing’s syndrome include weight gain, an accumulation of fat around the base of the neck, a fatty hump between the shoulders, the appearance of a “moon face”, and easy bruising. However, not all individuals with the syndrome exhibit these symptoms, rendering diagnosis challenging. Without timely treatment, Cushing’s syndrome can lead to severe complications, including heart attack, stroke, blood clots in the legs and lungs, increased susceptibility to infections, memory loss, and type 2 diabetes.

Dexamethasone testing

A commonly used method for diagnosing Cushing’s syndrome is the dexamethasone suppression test (DST), which measures the adrenal gland’s response to adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH).

ACTH regulates cortisol levels in the blood plasma and stimulates the adrenal cortex to produce cortisol. When cortisol levels increase, ACTH secretion is suppressed. Dexamethasone, a synthetic steroid similar to cortisol, is administered during the DST to lower ACTH levels.

DSTs are available in low-dose (LDDST) and high-dose (HDDST). They can be performed overnight or over two days.

LDDSTs are used initially to diagnose Cushing’s syndrome. If the result is positive, HDDSTs help classify the disease as ACTH-dependent or independent. These tests are typically conducted in the following manner.2

Cortisol is a steroid hormone of the glucocorticoid class made by the adrenal glands.

Image Credit: Shutterstock/Kateryna Kon

LDDST

- Overnight protocol: 1 mg of dexamethasone is administered at 11:00 pm, and the serum cortisol levels are measured at 8:00 am the following morning.

- Two-day protocol: serum cortisol levels are measured at 8:00 am and 0.5 mg of dexamethasone is administered every six hours (9:00 am, 3:00 pm, 9:00 pm, 3:00 am) for two days, totalling 4 mg. Serum cortisol levels are then measured at 9:00 am, six hours after the last dose has been delivered.

HDDST

- Overnight protocol: baseline serum cortisol or 24-hour urinary free cortisol (UFC) is measured in the morning, and 8 mg of dexamethasone is given at 11.00 pm. Cortisol level in blood is then measured at 8.00 am the following morning.

- Two-day protocol: Baseline serum cortisol or 24-hour UFC is measured at 8:00 am; 2 mg of dexamethasone is administered every six hours (9:00 am, 3:00 pm, 9:00 pm, 3:00 am) for two days, totaling 16 mg, in tandem with the collection of urine for UFC measurements. Serum cortisol levels are measured at 9:00 am, six hours after the last dose.

Patients whose pituitary glands produce excessive amounts of ACTH will exhibit an abnormal response to the low-dose test but a normal reaction to the high-dose test.

During the LDDST, cortisol levels should decrease following the administration of dexamethasone, and a cut-off value of below 18 ng/mL is recommended to distinguish a healthy response from an unhealthy one.

For the HDDST, a decrease in urine-free cortisol (UFC) or serum cortisol greater than 50% indicates the presence of ACTH-dependent Cushing’s syndrome. This rule applies to both the overnight LDDST and the two-day HDDST methods.

Measuring cortisol levels

Chemiluminescence immunoassay (CLIA) is a widely used method for measuring cortisol and other steroids due to its simplicity, automation, and good sensitivity.

However, it has some drawbacks, including cross-reactivity leading to overestimation of target analyte levels, non-standardization of kits, and the inability to measure more than one analyte per analysis. This is particularly problematic since studies indicate that measuring dexamethasone in combination with cortisol can reduce the number of false-positive DST results and improve interpretability. 3,4,5

Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) has emerged as a popular alternative to CLIA for DSTs due to its ability to measure multiple analytes simultaneously and its superior specificity.

Analytes are separated via LC, and their concentrations are measured by MS, with triple quadrupole MS configurations commonly used for this purpose. This technique provides the ability to measure multiple analytes simultaneously, along with higher accuracy and sensitivity than CLIA.

Increased ease of use and accuracy

In the Division of Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Metabolism at the University of Turin, a team has developed an LC-MS/MS technique for simultaneous quantifying cortisol, cortisone, dexamethasone, and six other exogenous corticosteroids in serum/plasma samples.6

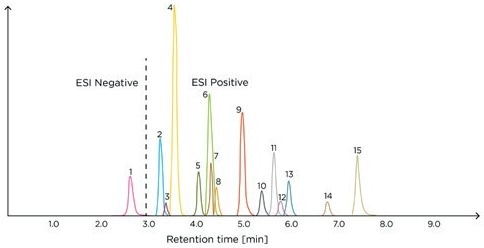

This method can be readily applied in any clinical laboratory equipped with a mass spectrometer and is effective in DSTs, enabling precise measurements of the target analytes in a single chromatographic run (Figure 1).

Sample preparation (1 Hour)

- Dilute 200 μL of the serum/plasma sample with 200 μL of water.

- Perform supported liquid extraction, manually transferring 400 μL of sample to a microplate.

- Apply positive pressure using Tecan Resolvex® A200 automated positive pressure processor.

- Elute with 700 μL of methyl tert-butyl ether.

- Evaporate and reconstitute in H2 O/MeOH (1:1, v/v).

- Agitate.

LC-MS/MS analysis (10 Minutes)

- LC column: C18 (100 × 2.1 mm, 1.7 μm)

- Flow rate: 400 μL/min

- Temperature: 30 °C

- Injection volume: 20 μL

- Mobile phase A: H2O + 0.2 mM ammonium fluoride

- Mobile phase B: acetonitrile

- Elution programme: Table 1.

The study demonstrated a strong correlation between the results obtained from the newly developed LC-MS/MS method and those obtained using a commercially available CE IVD-marked Steroid Panel LC-MS* kit (Tecan).

The Tecan kit enables simultaneous dexamethasone, cortisol, and cortisone measurement and includes all the necessary components for easy implementation, such as calibrators and controls. The samples are prepared using solid-phase extraction (SPE), which can be semi-automatically performed on a Resolvex® A200 positive pressure processor (Tecan). The kit can measure 15 other steroids in the core steroid metabolism pathway due to the effectiveness of the SPE process.

Table 1. LC gradient elution programme. Source: Tecan

| Time (min) | Mobile phase A (%) | Mobile phase B (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 90 | 10 |

| 0.5 | 65 | 35 |

| 4.5 | 65 | 35 |

| 4.51 | 35 | 65 |

| 6.0 | 2 | 98 |

| 8.0 | 2 | 98 |

| 8.01 | 90 | 10 |

| 10.0 | 90 | 10 |

* In USA: for research use only. Not for use in diagnostic procedures. Product availability and regulatory status may vary from country to country. Consult with your Tecan associate for further information.

Figure 1. Example chromatogram of the Steroid Panel LC-MS internal standard – run 1. ESI, electrospray ionization; 1, aldosterone; 2, cortisone; 3, dehydro-epiandrosterone sulfate; 4, cortisol; 5, 21-deoxycortisol; 6, corticosterone; 7, dexamethasone; 8, 11-deoxycortisol; 9, androstenedione; 10, 11-deoxycorticosterone; 11, testosterone; 12, dehydroepiandrosterone; 13, 17-hydroxyprogesterone; 14, dihydrotestosterone; 15, progesterone.

Image Credit: Tecan

Summary

Early diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome is critical to prevent potentially fatal complications. A reliable method for reducing the number of false positives in DSTs involves the simultaneous measurement of cortisol and dexamethasone levels, which can be accurately achieved using LC-MS/MS.

The LC-MS/MS method described in this article enables the simultaneous measurement of multiple analytes, such as cortisol, cortisone, and dexamethasone, in serum or plasma.

This analytical approach can provide clinical laboratories with a straightforward method for performing DSTs, and the commercially available kit can ensure consistent and dependable results.

References and further reading

- Cushing’s syndrome [website]. National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases 2018 (https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/endocrine-diseases/cushings-syndrome).

- Dogra P, Vijayashankar NP. Dexamethasone suppression test. StatPearls 2022, 8 August (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK542317 ).

- Ceccato F, Artusi C, Barbot M, et al. Dexamethasone measurement during low-dose suppression test for suspected hypercortisolism: threshold development with and validation. J Endocrinol Invest 2020;43(8):1105–1113. doi: 10.1007/s40618-020-01197-6.

- Roper SM. Yield of serum dexamethasone measurement for reducing false-positive results of low-dose dexamethasone suppression testing. J Appl Lab Med 2021;6(2):480–485. doi: 10.1093/jalm/jfaa193.

- Fleseriu M, Auchus R, Bancos I, et al. Consensus on diagnosis and management of Cushing’s disease: a guideline update. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 2021;9(12):847–875. doi: 10.1016/S2213- 8587(21)00235-7.

- Ponzetto F, Parasiliti-Caprino M, Settanni F, et al. Simultaneous measurement of cortisol, cortisone, dexamethasone and additional exogenous corticosteroids by rapid and sensitive LC-MS/MS analysis. Molecules 2022;28(1):248. doi: 10.3390/molecules28010248.

Filed under: Cushing's, Diagnostic Testing, symptoms | Tagged: cortisol, dexamethasone suppression test, diabetes, heart attack, stroke | Leave a comment »

View Full Size

View Full Size