Abstract

Introduction

Neuroendocrine tumours of the thymus are extremely rare, with an estimated incidence of about 1 in 5 million people. Although data is limited, complete surgical resection remains the most significant prognostic factor for improved survival and disease-free outcomes, with adjuvant radiotherapy playing a role in cases where resection margins are close. This case report details the management of a cortisol secreting pT1bN0 atypical carcinoid of the thymus in a 43-year-old male.

Case report

43-year-old male presented with Cushing’s syndrome and was diagnosed with a cortical secreting atypical carcinoid of the thymus. He underwent a robotic thymectomy. Recurrent disease on a DOTATATE-PET CT scan resulted in a second surgery involving complete resection of the mediastinal tumour which had invaded the pericardium, as well as wedge resection of the lung and lymph node sampling. This was followed by adjuvant radiotherapy due to close proximity of the lesion to the margin (< 3 mm).

Discussion

Although paraneoplastic syndromes such as Cushing’s syndrome are rare manifestations of thymic neuroendocrine tumours and can result in challenging diagnoses, it is vital to have a high index of suspicion towards ectopic ACTH secretion in order to facilitate timely initiation of multimodal disease management for these patients including surgery and radiotherapy.

Conclusion

Surgical management has been shown to offer the greatest prognosis in terms of overall survival and disease-free survival. Adjuvant radiotherapy plays a role where resection margins are close.

Introduction

Neuroendocrine tumours of the thymus (NETT) are extremely rare, with an estimated incidence of about 1 in 5 million people [1], accounting for about 2–5% of thymic tumours and 0.4–3.4% of all carcinoid tumours [2]. Around 50% of neuroendocrine tumours of the thymus are hormonally active, with patients presenting with paraneoplastic symptoms such as Cushing’s syndrome due to ectopic production of ACTH. A review of 157 cases showed that males have a 3:1 increased risk of developing NETTs compared to women [3], with patients typically being heavy smokers and diagnosed between 40 and 60 years old. Atypical carcinoid tumours are differentiated from typical carcinoid tumours by their increased mitotic rate (2–10 per 2mm2/10 HPF) or areas of focal necrosis and account for about 40–50% of all thymic neuroendocrine tumours [1]. We present a case of a male patient who underwent complete excision and adjuvant radiotherapy for a neuroendocrine carcinoma with elevated mitotic count.

Case report

A previously fit and well 43-year-old male initially presented with features of Cushing’s syndrome, namely weight gain, hypertension and skin changes. He had a past medical history of polycystic kidney disease and asthma. The Cushing’s syndrome was found to be related to a 56 mm cortisol secreting pT1bN0 neuroendocrine carcinoma of the thymus. He underwent a right sided robotic thymectomy in July 2021.

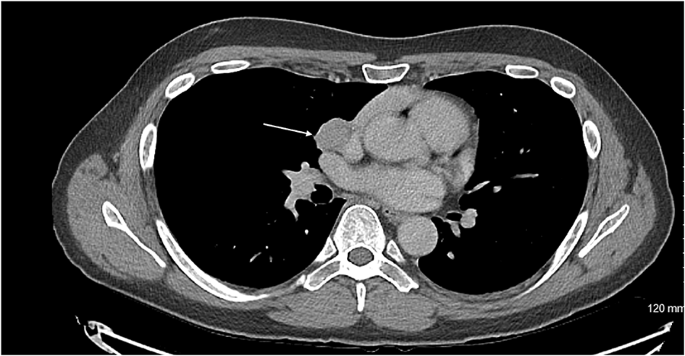

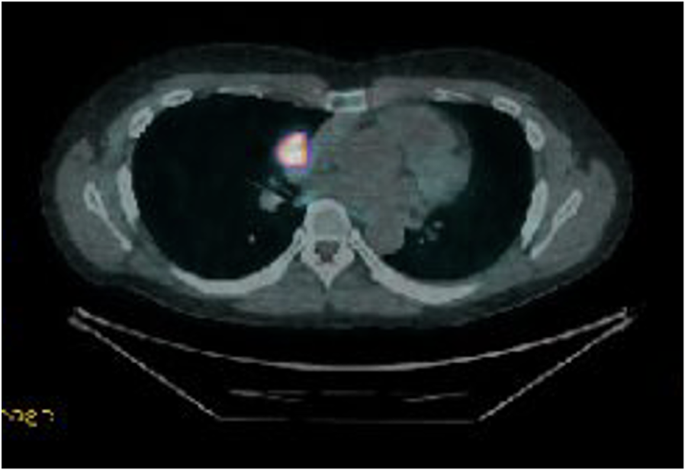

A DOTATATE PET CT scan showed recurrence of his thymic carcinoid at the level of the groove between the right main pulmonary artery and right atrium, growing very close to the phrenic nerve. It was advised for him to undergo complete excision of the lesion requiring a joint approach from cardiac and thoracic surgeons. The patient subsequently underwent a median sternotomy, removal of recurrent mediastinal tumour invading the pericardium and wedge resection of the lung, lymph node sampling.

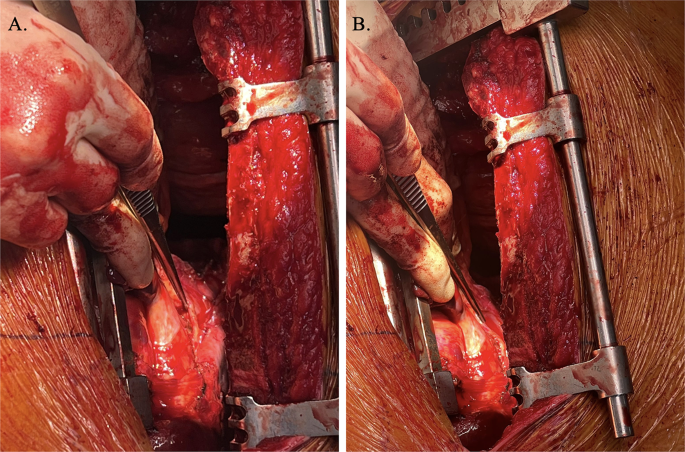

The patient was positioned supine. Femoral vessels were prepared in case there was bleeding which necessitated emergency bypass. Median sternotomy was performed with an oscillating saw due to previous right robotic thymectomy. The pericardium was opened. The tumour was identified at the level of the pulmonary vein and the cavo-atrial junction. En bloc resection of the tumour and the pericardium was performed, dissecting it away from the superior vena cava and the right atrium and wedge resection of the right lower lobe. The right phrenic was identified and spared. Due to previous surgery the phrenic nerve was surrounded by adhesions. A diaphragmatic plication was performed with 4 Ethibond no.5 sutures considering the risk of nerve palsy during dissection. The pericardium was reconstructed with a Prolene mesh fixed with Prolene 3/0.

Histology of the mediastinal tissue and right lung tissue sent showed a mitotic rate of more than 10 which according to the WHO classification of thoracic tumours, would make this a large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma. However, the morphological features were not of large cell type and therefore the tumour was best described as a NETT with elevated mitotic count. Histology confirmed the diagnosis as being a Neuroendocrine Carcinoma. The tumour had been excised completely with a 1.3 mm margin around the lesion. The patient required adjuvant radiotherapy due to the close proximity of the lesion to the margin (< 3 mm). A dose of 60 Gy over 30 daily fractions was selected in this postoperative adjuvant setting.

Discussion

This patient presented initially with Cushing’s syndrome associated with a cortisol secreting atypical carcinoid of the thymus. The excess glucocorticoid secretion presenting in the symptoms of Cushing’s syndrome can result from an ACTH secreting tumour of the pituitary which would be defined as Cushing’s disease, or less frequently from non-pituitary tumours secreting ACTH which would be defined as ectopic ACTH secretion [4]. Once the diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome is made, it is essential to differentiate whether this is Cushing’s disease or an ectopic ACTH secretion. Current guidelines advise that inferior petrosal sinus sampling is the gold standard in distinguishing Cushing’s disease from ectopic ACTH secretion where a pituitary MRI is negative [5]. However, due to high cost, invasive nature and the risk of thromboembolic complications, investigations such as the CRH test and high dose dexamethasone suppression test are often preferred. A retrospective analysis looked at 719 patients with neuroendocrine tumours treated in EKPA-Laiko Hospital in Athens, Greece. They found that the prevalence of endocrine neoplastic syndromes in patients with neuroendocrine tumours was only 1.9% [6]. Kamp et al. studied the prevalence of specifically ectopic ACTH syndrome in 918 patients who had been diagnosed with either thoracic or gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine tumours. They found that 29 patients, or 3.2% had ectopic ACTH syndrome, with most of these cases being thoracic tumours and 4 of these patients having thymic tumours [7]. This study highlights that although the incidence of ectopic ACTH secretion in thoracic neuroendocrine tumours is relatively rare, resulting in challenging diagnosis, it is important to maintain a high index of suspicion in order to facilitate timely initiation of multimodal management such as surgery and radiotherapy.

A retrospective study at Fukuoka University Hospital looking at 9 cases of NETTs and 16 cases of thymic carcinomas, showed complete resection to be a statistically significant prognostic factor, with the 5-year survival rate and 5-year disease free survival rate being 87.5% and 75% in the thymic neuroendocrine tumour group, and 58.9% and 57.1% in the thymic carcinoma group respectively [8]. Chen et al. looked at a total of 104 patients diagnosed with NETTs, of which 97 underwent surgical resection, with 79 undergoing radical resection. The 1-year, 3-year and 5-year overall survival rates were found to be 91.8%, 70.2% and 54.6% respectively, with radical resection being found to be a significant factor in the overall survival of patients with NETTs [9]. Due to the rarity of NETTs, few cases are reported, and these studies are limited by their being retrospective in nature and spanning over several decades, possibly affecting the consistency and standardisation of patient treatment. However, it is important to note that complete radical resection of the tumour was consistently shown to be a strong prognostic factor in the overall survival and disease-free survival of patients and this should be attempted wherever possible.

The gentleman in our case required post operative radiotherapy due to the close proximity of the lesion to the margins. A large retrospective study looked at 205 patients treated for neuroendocrine thymic tumours, with 81 patients receiving radiotherapy and 70 out of the 81 receiving it as adjuvant therapy. In this particular study, radiotherapy was not shown to have any significant impact on survival outcomes [10]. An analysis of 12 cases of NETTs noted that 5 of the 6 patients who had presented with local recurrence during follow up had not received any post operative radiotherapy [11, 12], suggesting that adjuvant radiotherapy had resulted in better outcomes in terms of disease-free survival. A large retrospective analysis looking at 1489 patients diagnosed with NETTs or thymic carcinomas, found that the two factors which influenced positive survival outcomes were surgical resection and adjuvant radiotherapy. On sub-analysis, it was found that adjuvant radiotherapy had a good prognosis of survival in patients with margin positive tumours and was an independent predictor of survival for both thymic carcinomas and NETTs [12]. Wen et al. analysed 3947 patients in a retrospective study, including 293 neuroendocrine thymic tumours, 2788 thymomas and 866 thymic carcinomas. It was shown that post operative radiotherapy had a significant positive impact on overall survival and cancer specific survival in Masaoka-Koga stage III-IV thymic neuroendocrine tumour patients, as well as had a favourable impact on the overall survival of stage IIB patients [13]. Although these studies provide evidence of the benefits of adjuvant radiotherapy for favourable outcomes and prolonged survival, the last two studies are limited in that due to the rarity of neuroendocrine thymic tumours, they made up only 11 out of 329 (3.3%) of the thymic tumours analysed by Bakhos et al. and 7.4% of cases analysed by Wen et al.l, and the outcomes should therefore be interpreted with caution. The importance of multidisciplinary care involving maximal radical surgical excision as well as the involvement of oncologists and radiotherapists in the management of thoracic carcinoid tumours such as this, is emphasised in Busetto et al. [14].

Conclusion

Neuroendocrine tumours of the thymus (NETT) are exceedingly rare and often present diagnostic and therapeutic challenges due to their aggressive nature and associated paraneoplastic syndromes like Cushing’s syndrome. Complete surgical resection remains the most significant prognostic factor for improved survival and disease-free outcomes, with adjuvant radiotherapy playing a role in cases where resection margins are close. Although the data is limited by the rarity of the disease, existing studies suggest that a multidisciplinary, patient-specific approach, including surgery and radiotherapy, offers the best chance of long-term survival.

Axial CT showing the carcinoid tumour (demonstrated by arrow) in close proximity to innominate vein

DOTATE PET demonstrating significant uptake in carcinoid tumour

Intraoperative visualisation right phrenic nerve (demonstrated by forceps) overlying carcinoid tumour

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

-

Bohnenberger H, Dinter H, König A, Ströbel P. Neuroendocrine Tumors Thymus Mediastinum J Thorac Dis [Internet]. 2017.

-

Lau J, Ioan Cvasciuc T, Simpson D, C de Jong M, Parameswaran R. Continuing challenges of primary neuroendocrine tumours of the thymus: A concise review. Eur J Surg Oncol [Internet]. 2022.

-

Chaer R, Massad MG, Evans A, Snow NJ, Geha AS. Primary neuroendocrine tumors of the thymus. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0003-4975(02)03547-6.

-

Isidori AM, Kaltsas GA, Pozza C, Frajese V, Newell-Price J, Reznek RH, et al. The ectopic adrenocorticotropin syndrome: clinical features, diagnosis, management, and long-term follow-up. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2005-1542.

-

Ilias I, Torpy DJ, Pacak K, Mullen N, Wesley RA, Nieman LK. Cushing’s syndrome due to ectopic corticotropin secretion: twenty years’ experience at the National Institutes of Health. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2004-2527.

-

Daskalakis K, Chatzelis E, Tsoli M, Papadopoulou-Marketou N, Dimitriadis GK, Tsolakis AV et al. Endocrine paraneoplastic syndromes in patients with neuroendocrine neoplasms. Endocrine [Internet]. 2018.

-

Kamp K, Alwani RA, Korpershoek E, Franssen GJH, de Herder WW, Feelders RA. Prevalence and clinical features of the ectopic ACTH syndrome in patients with gastroenteropancreatic and thoracic neuroendocrine tumors. Eur J Endocrinol [Internet]. 2015.

-

Midorikawa K, Miyahara S, Nishino N, Ueda Y, Waseda R, Shiraishi T, et al. Analysis of 25 surgical cases of thymic neuroendocrine tumors and thymic carcinoma. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13019-024-02723-w.

-

Chen Y, Zhang J, Zhou M, Guo C, Li S. Real-world clinicopathological features and outcome of thymic neuroendocrine tumors: a retrospective single-institution analysis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-022-02366-x.

-

Filosso PL, Yao X, Ahmad U, Zhan Y, Huang J, Ruffini E, et al. Outcome of primary neuroendocrine tumors of the thymus: a joint analysis of the international thymic malignancy interest group and the European society of thoracic surgeons databases. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.08.061.

-

Tiffet O, Nicholson AG, Ladas G, Sheppard MN, Goldstraw P. A clinicopathologic study of 12 neuroendocrine tumors arising in the thymus. Chest [Internet]. 2003.

-

Bakhos CT, Salami AC, Kaiser LR, Petrov RV, Abbas AE. Thymic neuroendocrine tumors and thymic carcinoma: demographics, treatment, and survival. Innovations: Technology and Techniques in Cardiothoracic and Vascular Surgery. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1177/1556984520949287.

-

Wen J, Chen J, Chen D, Liu D, Xu X, Huang L, et al. Evaluation of the prognostic value of surgery and postoperative radiotherapy for patients with thymic neuroendocrine tumors: a propensity-matched study based on the SEER database. Thorac Cancer. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1111/1759-7714.12868.

-

Busetto A, Comacchio GM, Verzeletti V, Fares Shamshoum, Fortarezza F, Pezzuto F et al. Bilateral metachronous typical and atypical carcinoid tumors of the lung. Thorac Cancer. 2025;16(8).

Acknowledgements

No acknowledgements.

Funding

This report has not received funding.

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work, ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013).

Consent for publication

Written informed consent was obtained from the patients for the publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editorial office of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

https://cardiothoracicsurgery.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13019-025-03629-x

Filed under: Cushing, Rare Diseases | Tagged: DOTATATE-PET CT scan, Neuroendocrine Thymic Tumour, pT1bN0 atypical carcinoid of the thymus | Leave a comment »