Cushing’s syndrome happens when the body has too much cortisol, the stress hormone. It can cause weight gain, high blood pressure, and diabetes. So how to keep your health in check and what are the treatment options available? In an exclusive interview with Times Now, an Endocrinologist explains its symptoms, causes, and treatments.

We often blame stress for everything—from sleepless nights to stubborn weight gain. But did you know your body’s stress hormone, cortisol, could be at the root of more serious health issues like high blood pressure and diabetes? Yes, you read that right! But how? We got in touch with Dr Pranav A Ghody, Endocrinologist at Wockhardt Hospital, Mumbai Central, who explains how excessive cortisol levels can lead to a condition known as Cushing’s Syndrome.

What Exactly is Cortisol, and Why is it Important?

Hormones are the body’s chemical messengers, travelling through the bloodstream to regulate essential functions. Among them, cortisol, produced by the adrenal glands (tiny glands sitting above the kidneys), plays a crucial role in controlling blood pressure, blood sugar, energy metabolism, and inflammation. The pituitary gland, located at the base of the brain, regulates cortisol through another hormone called Adrenocorticotropic Hormone (ACTH).

Often referred to as the “stress hormone,” cortisol spikes when we’re under stress. However, when levels remain high for too long, it can lead to Cushing’s Syndrome, a disorder first identified in 1912 by Dr Harvey Cushing.

What Causes Cushing’s Syndrome?

Dr Ghody explains that Cushing’s Syndrome occurs when the body is exposed to excessive cortisol, which can happen in two ways:

1. Exogenous (External) Cushing’s Syndrome

This is the most common form and results from prolonged use of steroid medications (such as prednisone) to treat conditions like asthma, rheumatoid arthritis, and lupus, or to prevent transplant rejection. Since steroids mimic cortisol, long-term use can disrupt the body’s hormone balance.

2. Endogenous (Internal) Cushing’s Syndrome

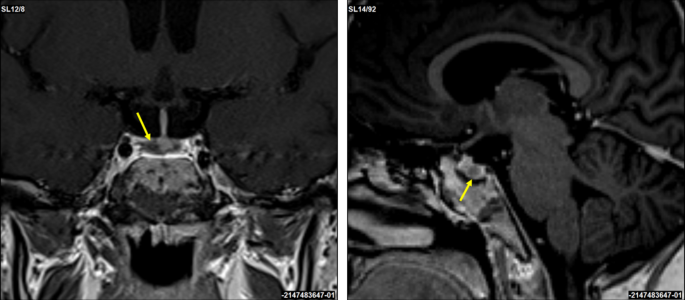

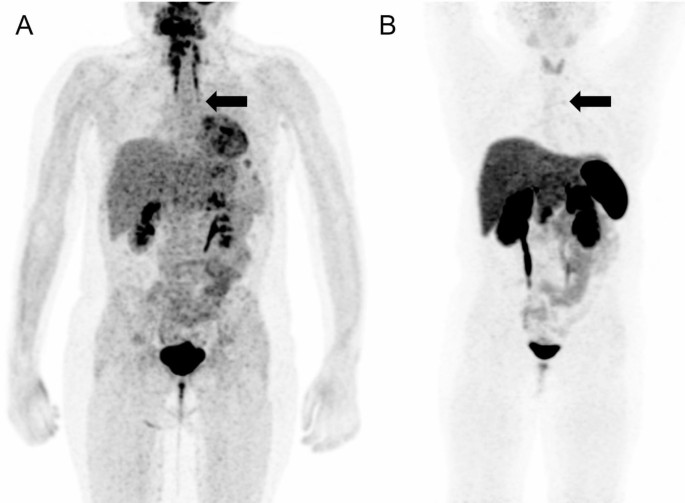

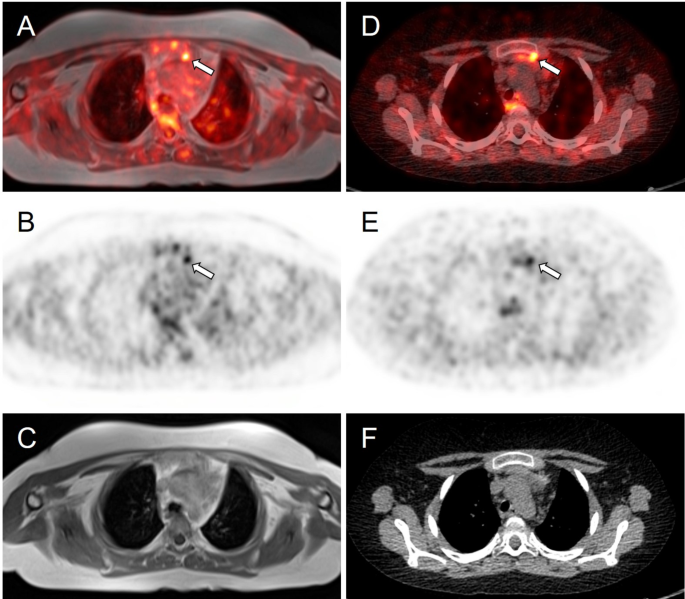

This occurs when the body produces too much cortisol due to a tumour in the pituitary gland, adrenal glands, or other organs (lungs, pancreas, thymus). While rare—affecting about 10 to 15 people per million annually—it’s more common in women between 20 and 50 years old. When caused by a pituitary tumour, it’s specifically called Cushing’s Disease.

Symptoms: How To Recognize Signs Of Cushing’s Syndrome

Excess cortisol affects multiple organs, leading to a variety of symptoms. This includes:

– Weight gain around the belly (central obesity)

– Rounded, puffy face (moon face)

– Excess facial and body hair (hirsutism)

– Fat accumulation on the upper back (buffalo hump)

– Thin arms and legs

– Dark red-purple stretch marks on the chest and abdomen

– Extreme fatigue and muscle weakness

– Depression or anxiety

– Easily bruising with minimal trauma

– Irregular menstrual cycles in women

– Reduced fertility or low sex drive

– Difficulty sleeping

High blood pressure and newly diagnosed or worsening diabetes are also common red flags.

Why is Cushing’s Syndrome Often Misdiagnosed?

Dr Ghody explains that while severe cases of Cushing’s Syndrome are easier to identify, milder forms can often be missed or mistaken for conditions like obesity, diabetes, or polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).

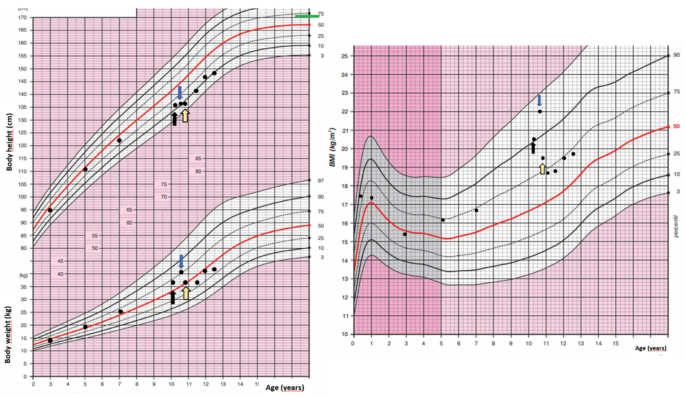

Diagnosing Cushing’s Syndrome involves:

1. Measuring cortisol levels in the blood, urine, or saliva.

2. Identifying the source through ACTH hormone testing, MRI/CT scans, and advanced techniques like Inferior Petrosal Sinus Sampling (IPSS) or nuclear medicine scans

Treatment Options: How is Cushing’s Syndrome Managed?

Once diagnosed, the treatment depends on the cause:

– If due to steroid medication, the dosage is gradually reduced under medical supervision.

– If caused by a tumour, surgery is the primary treatment. Some patients, especially those with pituitary tumours, may require repeat surgery, gamma knife radiosurgery, or medications to control cortisol levels.

Can You Prevent Cushing’s Syndrome?

While complete prevention isn’t always possible, Dr Ghody shares some key strategies to reduce risk:

– Use steroids cautiously – If prescribed, take the lowest effective dose for the shortest time. Never stop abruptly without consulting a doctor.

– Genetic screening for people at risk – If you have a family history of pituitary or adrenal tumours, regular monitoring can help with early detection.

– Maintain a healthy lifestyle – A diet rich in fresh vegetables, and fruits, low sodium intake, adequate calcium, and vitamin D can help manage the metabolic effects of excess cortisol.

– Avoid alcohol and tobacco – These can further disrupt hormone balance and overall health.

“Cushing’s Syndrome can be life-threatening if left untreated, but early diagnosis and proper management can significantly improve quality of life. So if you experience unexplained weight gain, blood pressure spikes, or other symptoms, consult an endocrinologist to manage hormonal imbalances,” he said.

Filed under: Cushing's, Diagnostic Testing, symptoms, Treatments | Tagged: blood pressure, cortisol, Cushing's Syndrome, diabetes, stress, Weight gain | Leave a comment »