Introduction

Primary adrenal insufficiency (PAI) is a condition resulting from impaired steroid synthesis, adrenal destruction, or abnormal gland development affecting the adrenal cortex.1 Acquired primary adrenal insufficiency is termed Addison disease. Central adrenal insufficiency (CAI) is caused by an impaired production or release of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH). It can originate either from a pituitary disease (secondary adrenal insufficiency) or arise from an impaired release of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) from the hypothalamus (tertiary adrenal insufficiency). An underlying genetic cause should be investigated in every case of adrenal insufficiency (AI) presenting in the neonatal period or first few months of life, although AI is relatively rare at this age (1:5.000–10.000).2

Physiology of the Adrenal Gland

The adrenal cortex consists of three zones: the zona glomerulosa, the zona fasciculata, and the zona reticularis, responsible for aldosterone, cortisol, and androgens synthesis, respectively.3 Aldosterone production is under the control of the renin-angiotensin system, while cortisol is regulated by the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA).4 This explains why patients affected by CAI only manifest glucocorticoid deficiency while mineralocorticoid function is spared. CRH is secreted from the hypothalamic paraventricular nucleus into the hypophyseal-portal venous system in response to light, stress, and other inputs. It binds to a specific cell-surface receptor, the melanocortin 2 receptor, stimulating the release of preformed ACTH and the de novo transcription of the precursor molecule pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC). ACTH is derived from the cleavage of POMC by proprotein convertase-1.5–9 ACTH binds to steroidogenic cells of both the zona fasciculata and reticularis, activating adrenal steroidogenesis. It also has a trophic effect on adrenal tissue; therefore, ACTH deficiency determines adrenocortical atrophy and decreases the capacity to secrete glucocorticoids. Circulating cortisol is 75% bound to corticosteroid-binding protein, 15% to albumin, and 10% free. The endogenous production rate is estimated between 6 and 10 mg/m2/day, even though it depends on age, gender, and pubertal development. Glucocorticoids have multiple effects: they regulate immune, circulatory, and renal function, influence growth, development, energy and bone metabolism, and central nervous system activity. Several studies reported higher cortisol plasma concentrations in girls than in boys and younger children.3,4,8

Cortisol secretion follows a circadian and ultradian rhythm according to varying amplitudes of ACTH pulses. Pulses of ACTH and cortisol occur every 30–120 minutes, are highest at about the time of waking, and decline throughout the day, reaching a nadir overnight.3,8,9 This pattern can change in the presence of serious illness, major surgery, and sleep deprivation. During stressful situations, glucocorticoid secretion can increase up to 10-fold to enhance survival through increased cardiac contractility and cardiac output, sensitivity to catecholamines, work capacity of the skeletal muscles, and availability of energy stores.3

The interaction between the hypothalamus and the two endocrine glands is essential to maintain plasma cortisol homeostasis (Figure 1). Cortisol exerts double-negative feedback on the HPA axis. It acts on the hypothalamus and the corticotrophin cells of the anterior pituitary, reducing CRH and ACTH synthesis and release.6 ACTH inhibits its secretion through a feedback effect mediated at the level of the hypothalamus.3 Increased androgen production occurs in the case of cortisol biosynthesis enzymatic deficits.

|

Figure 1 The hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis. |

Primary Adrenal Insufficiency

PAI affects 10–15 per 100,000 individuals and recognizes different classes of genetic causes (Table 1). Congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH) is the main cause of PAI in the neonatal period, being included among the disorders of steroidogenesis secondary to deficits in enzymes. It has an autosomal recessive transmission.1,10,11 The estimated incidence ranges between 1:10,000 and 1:20,000 births. CAH phenotype depends on disease-causing mutations and residual enzyme activity. 21-hydroxylase deficiency (21OHD) accounts for more than 90% of cases, 21-hydroxylase converts cortisol and aldosterone precursors, respectively 17-hydroxyprogesterone (17-OHP) to 11-deoxycortisol and progesterone to deoxycortisone. Less frequent forms of CAH include 11 β -hydroxylase deficiency (11BOHD, 8% of cases), 17α-hydroxylase/17–20 lyase deficiency (17OHD), 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase deficiency (3BHDS), P450 oxidoreductase deficiency (PORD).12 Steroidogenesis may also be impaired by steroidogenic acute regulatory (StAR) protein deficiency, which is involved in cholesterol transport into mitochondria, or P450 cytochrome side-chain cleavage (P450scc) deficiency, that converts cholesterol into pregnenolone.12,13 Of these conditions, 21OHD and 11BOHD only affect adrenal steroidogenesis, whereas the other deficits also impact gonadal steroid production. In classic CAH, enzyme activity can be absent (salt-wasting form) or low (1–2% enzyme activity, simple virilizing form). The salt-wasting form is the most severe and affects 75% of patients with classic 21OHD.1,10,12,14 Non-classic CAH (NCCAH) is more prevalent than the classic form, in which there is 20–50% of residual enzymatic activity. Two-thirds of NCCAH individuals are compound heterozygotes with different CYP21A2 mutations in two different alleles (classic severe mutation plus mild mutation in two different alleles or homozygous with two mild mutations). Notably, 70% of NCCAH patients carry the point mutation Val281Leu.

|

Table 1 Causes of Primary Adrenal Insufficiency (PAI) |

Central Adrenal Insufficiency

CAI incidence is estimated between 150 and 280 per million, and it should be suspected when mineralocorticoid function is preserved. When, rarely, isolated is due to iatrogenic HPA suppression secondary to prolonged glucocorticoid therapy or the removal of an ACTH- or cortisol-producing tumor (Cushing syndrome).15 Defects in POMC,16 characterized by red or auburn-haired children, pale skin (due to melanocyte stimulating hormone [MSH] – deficiency) and hyperphagia later in life, and in transcription factor TPIT,17 which regulates POMC synthesis in corticotrope cells, are the two leading genetic causes of isolated ACTH deficiency (Table 2). Mainly, it occurs as part of complex syndromes in which a combined multiple pituitary hormone deficiency (CMPD) is associated with craniofacial and midline defects, such as Prader-Willi syndrome, CHARGE syndrome, Pallister-Hall syndrome (anatomical pituitary abnormalities), white vanishing matter disease (progressive leukoencephalopathy).5 Individuals with an isolated pituitary deficiency, usually a growth hormone deficiency (GHD), may develop multiple pituitary hormone deficiencies over the years. Therefore, excluding a latent CAI at GHD onset and periodically monitoring of HPA axis is of utmost importance. Notably, cortisol reduction secondary to an increased basal metabolism when starting GHD or thyroxin substitutive therapy may unleash a misdiagnosed CAI. CMPD can be caused by several defective genes, such as GLI1, LHX3, LHX4, SOX2, SOX3, HESX1: in such cases, hypoglycemia or small penis with undescended testes may respectively suggest concomitant GH and gonadotropins deficits.18

|

Table 2 Causes of Central Adrenal Insufficiency (CAI) |

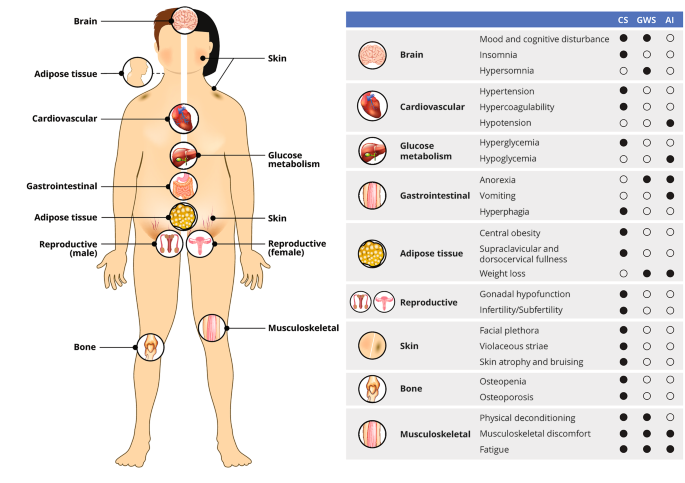

Clinical Manifestations of Adrenal Insufficiency

AI is an insidious diagnosis presenting non-specific symptoms and may be mistaken with other life-threatening endocrine conditions (septic shock unresponsive to inotropes or recurrent sepsis, acute surgical abdomen).1,19 Children can be initially misdiagnosed as having sepsis, metabolic disorders, or cardiovascular disease, highlighting the need to consider adrenal dysfunction as a differential diagnosis for an unwell or deteriorating infant. With age-related items, clinical features depend on the type of AI (primary or central) and could manifest in an acute or chronic setting (Table 3).

|

Table 3 Features of Isolated Adrenal Insufficiency in Pediatric Age |

Clinical signs of PAI are based on the deficiency of both gluco- and mineralocorticoids. Signs due to glucocorticoid deficiency are weakness, anorexia, and weight loss. Hypoglycemia with normal or low insulin levels is frequent and often severe in the pediatric population. Mineralocorticoid deficiency contributes to hyponatremia, hyperkalemia, acidosis, tachycardia, hypotension, and salt craving. The lack of glucocorticoid-negative feedback is responsible for the elevated ACTH levels. The high levels of ACTH and other POMC peptides, including the various forms of MSH, cause melanin hypersecretion, stimulating mucosal and cutaneous hyperpigmentation. Searching for an increased pigmentation may represent an essential diagnostic tool since all the other symptoms of PAI are non-specific. However, hyperpigmentation is variable, dependent on ethnic origin, and more prominent in skin exposed to sun and in extension surface of knees, elbows, and knuckles.15 In autoimmune PAI, vitiligo may be associated with hyperpigmentation.

In the classic CAH simple virilizing form, salt wasting is absent due to the presence of aldosterone production. In males, diagnosis typically occurs between 3 and 4 years of age with pubarche, accelerated growth velocity, and advanced bone age at presentation.1,10,12,14

NCCAH may occur in late childhood with signs of hyperandrogenism (premature pubarche, acne, adult apocrine odor, advanced bone age) or be asymptomatic. In adolescents and adult women, conditions of androgen excess (acne, oligomenorrhea, hirsutism) may underlie an NCCAH.20,21

The clinical presentation of CAI may be more complex when caused by an underlying central nervous system disease or by CMPD. In the case of a pituitary or hypothalamic tumor, patients may present headache, vomiting, visual disturbances, short stature, delayed or precocious puberty. In the case of CMPD, manifestations vary considerably and depend on the number and severity of the associated hormonal deficiencies. In CAI, aldosterone production is spared, which means that serum electrolytes are usually normal. However, cortisol contributes to regulating free water excretion, so patients with CAI are at risk for dilutional hyponatremia, with normal serum potassium levels. Since adrenal androgen secretion is under the control of ACTH, girls with ACTH deficiency may present light pubic hair. Patients with partial and isolated ACTH defects can be “asymptomatic”, and adrenal crisis appears during stress or in case of major illness (high fever, surgery).

The acute adrenal crisis is a life-threatening condition in all ages. Patients present with profound malaise, fatigue, nausea, vomiting, abdominal or flank pain, muscle pain or cramps, and dehydration, which lead to hypotension, shock, and metabolic acidosis. Hyponatremia and hyperkalemia are less common in CAI than in PAI, but possible in acute AI. Severe hypoglycemia causes weakness, pallor, sweatiness, and impaired cognitive function, including confusion, loss of consciousness, and coma. Immediate treatment is required (see below).

Children and adolescents affected by autoimmune primary adrenal insufficiency develop a chronic AI, with an insidious onset and slow progress to an acute adrenal crisis over months or even years. Initial symptoms are decreased appetite, anorexia, nausea, abdominal pain, unintentional weight loss, lethargy, headache, weakness, and fatigue, with prominent pain in the joints and muscles. Due to salt loss through the urine and the subsequent reduction in blood volume, blood pressure decreases, and orthostatic hypotension develops together with salt craving. An increased risk of infection in AI patients is reported only in those exposed to glucocorticoids. However, in APECED (Autoimmune Polyendocrinopathy-Candidiasis- Ectodermal-Dystrophy) patients, there is an increased risk of candidiasis and splenic atrophy increases the likelihood for severe infections.

In neonates, AI classically presents with failure to thrive and hypoglycemia, commonly severe and associated with seizures. The condition can be life-threatening and, if misdiagnosed, may result in coma and unexplained neonatal death. In newborns, cortisol deficiency causes delayed bile acid synthesis and transport maturation, determining prolonged cholestatic jaundice with persistently raised serum liver enzymes. The cholestasis can be resolved within ten weeks of correct treatment. StAR deficiency and P450scc cause salt-losing AI with female external genitalia in genetically male neonates.22 In the classic CAH salt-wasting form, the mineralocorticoid deficiency presents with the adrenal crisis at 10–20 days of life. Females show atypical genitalia with signs of virilization (clitoral enlargement, labial fusion, urogenital sinus), whereas males have normal-appearing genitalia, except for subtle signs as scrotal hyperpigmentation and enlarged phallus.1,10,12,14 Neonates with CMPD may display non-specific symptoms including hypoglycemia, lethargy, apnea, poor feeding, jaundice, seizures, hyponatremia without hyperkalemia, temperature and hemodynamic instability, recurrent sepsis, and poor weight gain. A male with hypogonadism may have undescended testes and micropenis. Infants with optic nerve hypoplasia or agenesis of the corpus callosum may present with nystagmus. Furthermore, infants with midline defects may have various neuro-psychological problems or sensorineural deafness.

Genetic Disorders and Other Conditions at Increased Risk for Adrenal Insufficiency

Among the cholesterol biosynthesis disorder, there is the Smith-Lemli-Opitz syndrome,23 where microcephaly, micrognathia, low-set posteriorly rotated ears, syndactyly of the second and third toes, and atypical genital may, although rarely, combine with AI; this autosomal recessive disorder is due to defective 7-dehydrocholesterol reductase so that elevated 7-dehydrocholesterol is diagnostic. In lysosomal acid lipase A deficiency,24 AI is due to calcification of the adrenal gland as a result of the accumulation of esterified lipids; in infantile form, that is Wolman disease, hepatosplenomegaly with hepatic fibrosis and malabsorption lead to death in the first year of life, if not treated with enzyme replacement therapy such as sebelipase alfa.25

Adrenal development may be impaired in X-linked congenital adrenal hypoplasia (AHC),13,26 a disorder caused by defective nuclear receptor DAX-1, presenting with salt-losing AI in infancy in approximately half of the cases, but also later in childhood or adolescence with two other key features such as hypogonadotropic hypogonadism and impaired spermatogenesis. Two syndromes combine adrenal hypoplasia with intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR): in IMAGe syndrome,27 caused by CDKN1C gain-of-function mutations, IUGR and AI present with metaphyseal dysplasia and genitourinary anomalies; MIRAGE syndrome28 is instead characterized by myelodysplasia, infections, genital abnormalities, and enteropathy, as a result of gain-of-function mutations in SAMD9, with elevated mortality rates.

In some other conditions, AI is due to ACTH resistance. Familial Glucocorticoid Deficiency type 1 (FGD1)13,29 and type 2 (FGD2)30 derive from defective ACTH receptor (MC2R) or its accessory protein MRAP, and both present with early glucocorticoid insufficiency (hypoglycemia, prolonged jaundice) and pronounced hyperpigmentation; there is usually an excellent response to cortisol replacement therapy, even though ACTH levels remain elevated.

In Allgrove or Triple-A Syndrome,13,31 defective Aladin protein (an acronym for alacrimia-achalasia-adrenal insufficiency) leads to primary ACTH-resistant adrenal insufficiency with achalasia and absent lacrimation, often combined with neurological dysfunction, either peripheral, central, or autonomic. It is an autosome recessive condition, phenotypically characterized by microcephaly, short stature, and skin hyperpigmentation.32,33

Among metabolic disorders associated with AI, Sphingosine-1-Phosphate Lyase (SGPL1) Deficiency34 is a sphingolipidosis with various features such as steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome, primary hypothyroidism, undescended testes, neurological impairment, lymphopenia, ichthyosis; interestingly, in cases where nephrotic syndrome develops before AI, the latter may be masked by glucocorticoid treatment.

Adrenoleukodystrophy (ALD)35–37 is an X-linked recessive proximal disorder of beta-oxidation due to defective ABCD1, where the accumulation of very-long-chain fatty acids (VLCFA) affects in almost all cases adrenal gland among other tissues. Most patients present with progressive neurological impairment, but in some, AI is the only (approximately 10%) or first manifestation, so that every unexplained AI in boys should receive plasma VLCFA evaluation to diagnose ALD and reduce cerebral involvement through a low VLCFAs diet (Lorenzo’s oil) and allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Early disease-modifying therapies have been developed. Gene therapy adds new functional copies of the ABCD1 gene in hematopoietic stem cells through a lentiviral vector reinfusing the modified cells in the patient’s bloodstream. Recent trials show encouraging results.38

In Zellweger syndrome, caused by mutations in peroxin genes (PEX), peroxisomes are absent, and disease presentation occurs in the neonatal period, with low survival rates after the first year of life. Finally, mitochondrial disorders have been described to occasionally develop AI: Pearson syndrome (sideroblastic anemia, pancreatic dysfunction), MELAS syndrome (encephalopathy with stroke-like episodes), and Kearns-Sayre syndrome (external ophthalmoplegia, heart block, retinal pigmentary changes) belong to this class.39

Autoimmune pathogenesis (Addison disease) accounts for approximately 15% of cases of primary AI in children, in contrast with adolescents and adults where it is the most common mechanism; half of these children present other glands involvement as well. Two syndromes recognize specific combinations: in Autoimmune Polyglandular Syndrome Type 1 (APS1, or APECED)40 defective autoimmune regulator AIRE causes AI, hypoparathyroidism, hypogonadism, malabsorption, chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis; APS2 usually present later in life (third-fourth decades) with AI, thyroiditis, and type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM). Antibodies against 21-hydroxylase enzyme are the hallmark of APS.

Apart from a genetic disorder, a strong link between autoimmune conditions and autoimmune primary AI has been established, with more than 50% of patients with the latter also having one or more other autoimmune endocrine disorders; on the other hand, only a few patients with T1DM or autoimmune thyroiditis or Graves’ disease develop AI. As an example, in a study of 629 patients with T1DM, only 11 (1.7%) presented 21-hydroxylase autoantibodies, with three of them having AI.41 Nevertheless, these patients are to be considered at increased risk for a condition that is potentially fatal yet easy to diagnose and treat; that is why it is reasonable to screen for autoimmune AI at least patients with T1DM, significantly if associated with DQ8 HLA combined with DRB*0404 HLA alleles, who have been observed to develop AI in 80% of cases if also 21-hydroxylase autoantibodies positive.42

Regarding immunological disruption, the link with celiac disease is instead well established: celiac patients have an 11-fold increased risk for AI, while in a study, 6 of 76 patients with AI had celiac disease, so that mutual evaluation should be granted in these patients.43,44

Subclinical Adrenal Insufficiency

Subclinical AI is a particularly insidious challenge for a pediatric endocrinologist. It represents the preclinical stage of Addison disease when 21-hydroxylase autoantibodies are already detectable but still absent from evident symptoms. 21-hydroxylase autoantibodies positivity carries a greater risk to develop overt AI in children than in adults: in a study, estimated risk was 100% in children versus 32% in adults on a medium six-year period of follow-up.45 As the adrenal crisis is a potentially lethal condition, it is essential to recognize and adequately manage subclinical AI.

Although asymptomatic by definition, subclinical AI may present with non-specific symptoms such as fatigue, lethargy, gastrointestinal symptoms (nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, constipation), hypotension; physical or psychosocial stresses may sometimes exacerbate these symptoms. When symptoms lack, subclinical AI may be identified thanks to the co-occurrence with other autoimmune endocrinopathies.46

21-hydroxylase autoantibodies titer is considered a marker of autoimmune activity and correlates with disease progression.47 Other reported risk factors for the disease evolution include young age, male sex, hypoparathyroidism or candidiasis coexistence, increased renin activity, or an altered synacthen test with normal baseline cortisol and ACTH.45 ACTH elevation has been reported as the best predictor of progression to the clinical stage in 2 years (94% sensitivity and 78% specificity).48

Management of patients with subclinical AI should include serum cortisol, ACTH, renin measurement, and a synacthen test. If normal, cortisol and ACTH should be repeated in 12–18 months, while synacthen test every two years. After synacthen test results are subnormal, cortisol and ACTH should be assessed every 6–9 months if ACTH remains in range or every six months if ACTH becomes elevated.49 In the latter case, therapy with hydrocortisone should be started.19 This strategy will prevent acute crises and possibly improve the quality of life in patients reporting non-specific symptoms.

Diagnosis

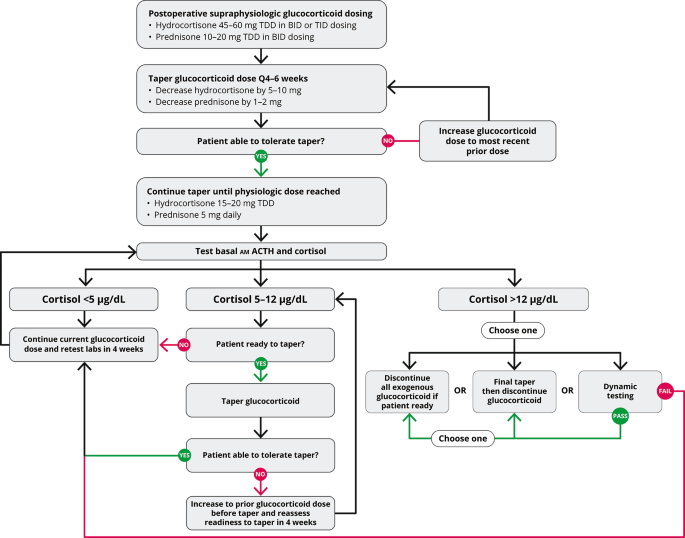

Laboratory evaluation of a stable patient with suspected AI should start with combined early morning (between 6 and 8 AM) serum cortisol and ACTH measurements (Figure 2).

|

Figure 2 Diagnostic algorithm for adrenal insufficiency. |

Although often included in the extensive work-up of an unwell child, a single cortisol value is usually challenging to interpret: circadian cortisol rhythm is highly variable and morning peak is unpredictable; morning cortisol levels in children with diagnosed AI may range up to 706 nmol/L (97th percentile); several factors, such as exogenous estrogens, may alter total serum cortisol values by influencing the free cortisol to cortisol binding globulin or albumin-bound cortisol ratio.7

Significant variability is also observed depending on the specific type of cortisol assay; therefore, it is recommended to check the reference ranges with the laboratory. Mass spectrometry analysis and the new platform methods (Roche Diagnostics Elecsys Cortisol II)50 have more specificity because it detects lower cortisol concentrations than standard immunoassays.15 Low serum cortisol with normal or low ACTH levels is compatible with CAI. In such cases, morning serum cortisol levels below 3 µg/dL (83 nmol/L) best predict AI, while greater than 13 µg/dL (365 nmol/L) values tend to exclude it.51 This is why in most cases, a dynamic test is required for diagnosis and has been introduced to assess the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis in case of intermediate values.5

The insulin tolerance test (ITT) is considered the gold standard for CAI diagnosis as hypoglycemia results in an excellent HPA axis activation; moreover, it allows simultaneous growth hormone evaluation in patients with suspected CPHD. Serum cortisol is measured at baseline and 15, 30, 45, 60, 90, and 120 minutes after intravenous administration of 0.1 UI/Kg regular insulin; the test is valid if serum glucose is reduced by 50% or below 2.2 mmol/L (40 mg/dL).52 CAI is diagnosed for a <20 µg/dL (550 nmol/L) cortisol value at its peak.15 Hypoglycemic seizures and hypokalemia (due to glucose infusion) are the main risks of this test so that it is contraindicated in case of a history of seizures or cardiovascular disease.

Glucagon stimulation test (GST, 30 µg/Kg up to 1 mg i.m. glucagon with cortisol measurements every 30 min for 180 min) allows both CAI and growth hormone deficiency evaluation as well but is characterized by frequent gastrointestinal side effects and poor specificity.8

Metyrapone is an 11-hydroxylase inhibitor, thereby decreasing cortisol synthesis and removing its negative feedback on ACTH release. Overnight metyrapone test is based on oral administration of 30 mg/Kg metyrapone at midnight, and 11-deoxycortisol measurement on the following morning: in case of CAI, its level will not reach 7 µg/dL (200 nmol/L). This test may, however, induce an adrenal crisis so that it is rarely performed.

Given their safety profile and accuracy, corticotropin analogs such as tetracosactrin (Synacthen®) or cosyntropin (Cortrosyn®) are recommended as first-line stimulation tests. Nevertheless, false-negative results are probable in the case of recent or moderate ACTH deficiency, which would not have induced adrenal atrophy. The standard dose short synacthen test (SDSST) is based on a 250 µg Synacthen vial administration with serum cortisol measurement at baseline and 30 and 60 minutes after. CAI is diagnosed if peak cortisol level is <16 µg/dL (440 nmol/L), or excluded if >39 µg/dL (1076 nmol/L). However, the cut-offs for both the new platform immunoassay and mass spectrometry serum cortisol assays are 13.5 to 14.9 mcg/dL (373 to 412 nmol/L).53 The 250 µg Synacthen dose is considered a supraphysiological stimulus since it is 500 times greater than the minimum ACTH dose reported to induce a maximal cortisol response (500 ng/1.73 m2). The low dose short synacthen test (LDSST) has been introduced as a more sensitive first-line test in children greater than two years.54 The recommended dose is 1 µg55, which is contained in 1 mL of the solution obtained by diluting a 250 µg vial into 250 mL saline. Serum cortisol level is then measured at baseline and after 30 minutes, resulting in diagnose of CAI if <16 µg/dL (440 nmol/L), otherwise ruling it out if >22 µg/dL (660 nmol/L). Using these thresholds, LDSST is more precise than SDSST in children, with an area under the ROC curve of 0.99 (95% CI 0.98–1.00).56 LDSST has not been validated in acutely ill patients, pituitary acute disorders or surgery or radiation therapy, and impaired sleep-wake cycle. Patients with an indeterminate LDSST result should be furtherly studied with ITT or metyrapone test.

Finally, the CRH test is based on 1 µg/Kg human CRH (Ferring®) administration and may differentiate secondary from tertiary AI, but its thresholds are still not precisely defined.57

Once CAI is diagnosed, other pituitary hormones should be assessed (prolactin, IGF1, LH, FSH, fT4, TSH), and an MRI of the pituitary region should be performed to exclude neoplastic or infiltrative processes.

Primary adrenal insufficiency (PAI) should be suspected in case of low serum cortisol with elevated ACTH levels. When hypocortisolemia has been confirmed, ACTH levels >66 pmol/L or greater than twice the upper limit best predict PAI. Nevertheless, a confirmatory dynamic test is always recommended for diagnosis.19 Given the comparable accuracy between standard and low dose SST reported in these patients, SDSST is recommended as the most feasible test.58 Moreover, suspected PAI cases should receive plasma renin activity or direct renin and aldosterone assessment to evaluate mineralocorticoid deficiency.

Etiologic work-up of confirmed PAI should start from 21-hydroxylase antibodies assessment: if positive, differential diagnosis will include Addison disease and APS1 or APS2. Adrenal autoantibody negative patients should instead be screened for CAH by measuring 17-hydroxyprogesterone, ALD (if young male) by assessing VLCFA, and tuberculosis if endemic; adrenal glands imaging will complete the work-up in order to exclude infection, hemorrhage, or tumor.6

While universal newborn screening is already implemented for CAH in many countries, allowing a timely replacement therapy, basal salivary cortisol, and salivary cortisone measurements could improve CAI screening in the future: this technique is simple, cost-effective, and independent of binding proteins.15

Treatment

All patients with adrenal insufficiency need long-term glucocorticoid replacement therapy. Individuals with PAI also require mineralocorticoids replacement, together with salt intake as required (Table 4). Otherwise, guidelines do not recommend androgen replacement.5,9,19

|

Table 4 Management of Adrenal Insufficiency (AI) |

Oral hydrocortisone is the first-choice replacement treatment in children due to its short half-life, rapid peak in plasma concentration, lower potency, and fewer adverse effects than prednisolone and dexamethasone.5,8 Based on endogenous production, dosing replacement regimens vary from 7.5 to 15 mg/m2/day, divided into two, three, or four doses.19 The first and largest dose should be taken at awakening, the next in the early afternoon to avoid sleep disturbances. Small and frequent dosing mimic the physiological rhythm of cortisol secretion, but high peak cortisol levels after drug assumption and prolonged periods of hypocortisolemia between doses are described.8,9 Some children experience low cortisol concentrations and symptoms of cortisol insufficiency (eg, fatigue, nausea, headache) despite modifications in dosing. This cohort of patients can take advantage of using a modified-release hydrocortisone formulation, such as Chronocort® and Plenadren®. Plenadren®, approved for adults, consists of a coating of hydrocortisone released rapidly, followed by a slow release of hydrocortisone from the tablet center. It is available as 5 and 20 mg tablets. Park et al demonstrate smoother cortisol profiles and normal growth and weight gain patterns using Plenadren® in children.59 In a few cases, the continuous subcutaneous infusion of hydrocortisone using insulin pump technology proved to be a feasible, well-tolerated and safe option for selected patients with poor response to conventional therapy.19

Monitoring glucocorticoid therapy is based on growth, weight gain, and well-being. Cortisol measurements are usually not useful, apart from cases when a discrepancy between daily doses and patient symptoms exists.15 The concomitant use of hydrocortisone and CYP3A4 inducers, such as Rifampicin, Phenytoin, Carbamazepine, requires an increased dose of glucocorticoids. Conversely, the inhibition of CYP3A4 impairs hydrocortisone metabolism.5

Mineralocorticoid replacement is unnecessary if the patient has a normal renin-angiotensin-aldosterone axis and, hence, normal aldosterone secretion, as well as in CAI. By contrast, patients with PAI and confirmed aldosterone deficiency need fludrocortisone at the dosage of 0.1–0.2 mg/day when given together with hydrocortisone, which has some mineralocorticoid activity. When using other synthetic glucocorticoids for replacement, higher fludrocortisone doses may be needed. Infants younger than one year should also be supplemented with sodium chloride due to their relatively low dietary sodium intake and relative renal resistance to mineralocorticoids. The dose is approximately 1 gram (17 mEq) daily.19

Surgery and anesthesia increase the glucocorticoid requirement during the pre-, intra-, and post-operative periods (Table 4). All children with AI should receive an intravenous dose of hydrocortisone at induction (2 mg/kg for minor or major surgery under general anesthesia). For minor procedures or sedation, the child should receive a double morning dose of hydrocortisone orally.60

Adrenal crisis is a life-threatening condition, treatment is effective if administered promptly, and it must not be delayed for any reason. Hydrocortisone should be administered as soon as possible with an intravenous bolus of 4 mg/kg followed by a continuous infusion of 2 mg/kg/day until stabilization. In the alternative, it can be administered as a bolus every four hours intravenous or intramuscular. In difficult peripheral venous access, the intramuscular route must be used as the first choice. In order to counteract hypotension, a bolus of normal saline 0.9% should be given at a dose of 20 mL/kg; it can repeat up to a total of 60 mL/kg within one hour for shock. If there is hypoglycemia, 10% dextrose at a 5 mL/kg dose should be administered.5,19,61,62

Patients with AI require additional doses of glucocorticoids in case of physiologic stress such as illness or surgical procedures to avoid an adrenal crisis. Home management of illness with a fever (> 38°C), vomiting or diarrhea, is based on the increase from two to three times the usual dose orally. If the child is unable to tolerate oral therapy, intramuscular injection of hydrocortisone should be administered (Table 4).

Education for caregivers and patients (if adolescent) is crucial to prevent adrenal crisis. They should recognize signs and symptoms of adrenal crisis and should receive a steroid emergency card with the sick day rules. Prescribing doctors should provide for additional oral glucocorticoids and adequate training in hydrocortisone emergency self-injection.

Abbreviations

AI, adrenal insufficiency; PAI, primary adrenal insufficiency; CAI, central adrenal insufficiency; HPA, hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis; CRH, corticotropin-releasing hormone; ACTH, adrenocorticotropic hormone; POMC, pro-opiomelanocortin; CAH, congenital adrenal hyperplasia; STAR, steroidogenic acute regulatory; 21OHD, 21-hydroxylase deficiency; 11BOHD, 11-B-hydroxylase deficiency; P450scc, P450 cytochrome side-chain cleavage deficiency; 17-OHP, 17-hydroxyprogesterone; NCCAH, non-classic congenital adrenal hyperplasia; ALD, adrenoleukodystrophy; VLCFA, very long-chain fatty acids; CMPD, combined multiple pituitary hormone deficiency; GHD, growth hormone deficiency; MSH, melanocyte stimulating hormone; IUGR, intrauterine growth restriction; APS1, autoimmune polyglandular syndrome type 1; SDSST, standard dose short synacthen test; LDSST, low dose short synacthen test.

Take Home Messages

- In neonates and infants CAH is the commonest cause of PAI, causing almost 71.8% of cases.

- Adrenoleukodystrophy should be considered in any male with hypoadrenalism.

- Unexplained hyponatremia, hyperpigmentation and the loss of pubic and axillary hair should raise the suspicion of AI.

- Adrenal insufficiency can present with non-specific clinical features; therefore a single cortisol measurement should be included in the biochemical work-up of an unwell child.

- Patients and parents should be well-trained in adrenal crisis recognition and management.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

1. Charmandari E, Nicolaides N, Chrousos G. Adrenal insufficiency. Lancet. 2021;383(9935):2152–2167. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61684-0

2. White PC. Adrenocortical insufficiency. In: Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. Elsevier. 2019:11575–11617.

3. White PC. Physiology of the adrenal gland. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. Elsevier. 2019.

4. Butler G, Kirk J. Adrenal gland disorders. In: Paediatric Endocrinology and Diabetes. Oxford University Press. 2020:274–288.

5. Patti G, Guzzeti C, Di Iorgi N, Loche S. Central adrenal insufficiency in children and adolescents. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;32(4):425–444. doi:10.1016/j.beem.2018.03.012

6. Martin-grace J, Dineen R, Sherlock M, Thompson CJ. Adrenal insufficiency: physiology, clinical presentation and diagnostic challenges. Clin Chim Acta. 2020;505:78–91. doi:10.1016/j.cca.2020.01.029

7. Shaunak M, Blair JC, Davies JH. How to interpret a single cortisol measurement. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract. 2020;105:347–351. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2019-318431

8. Park J, Didi M, Blair J. The diagnosis and treatment of adrenal insuf fi ciency during childhood and adolescence. Arch Dis Child. 2016;101:860–865. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2015-308799

9. Husebye ES, Pearce SH, Krone NP, Kämpe O. Adrenal insufficiency. Lancet. 2021;397:613–629. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00136-7

10. Speiser P, Azziz R, Baskin L, et al. Congenital adrenal hyperplasia due to steroid 21-hydroxylase deficiency: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(9):4133–4160. doi:10.1210/jc.2009-2631

11. Buonocore F, McGlacken-Byrne S, Del Valle I, Achermann J. Current insights into adrenal insufficiency in the newborn and young infant. Front Pediatr. 2020;8:619041. doi:10.3389/fped.2020.619041

12. Bacila I, Elder C, Krone N. Update on adrenal steroid hormone biosynthesis and clinical implications. Arch Dis Child. 2019;104(12):1223–1228. doi:10.1136/archdischild-2017-313873

13. Buonocore F, Maharaj A, Qamar Y, et al. Genetic analysis of pediatric primary adrenal insufficiency of unknown etiology: 25 years’ experience in the UK. J Endocr Soc. 2021;5(8):1–15. doi:10.1210/jendso/bvab086

14. Balsamo A, Baronio F, Ortolano R, et al. Congenital adrenal hyperplasias presenting in the newborn and young infant. Front Pediatr. 2020;8:593315. doi:10.3389/fped.2020.593315

15. Hahner S, Ross RJ, Arlt W, et al. Adrenal insufficiency. Nat Rev Dis Prim. 2021;7(1):1–24. doi:10.1038/s41572-021-00252-7

16. Krude H, Biebermann H, Luck W, et al. Severe early-onset obesity, adrenal insufficiency and red hair pigmentation caused by POMC mutations in humans. Nat Genet. 1998;19:155–157. doi:10.1038/509

17. Vallette-Kasic S, Brue T, Pulichino A-M, et al. Congenital isolated adrenocorticotropin deficiency: an underestimated cause of neonatal death, explained by TPIT gene mutations. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90:1323–1331. doi:10.1210/jc.2004-1300

18. Alatzoglou K, Dattani M. Genetic forms of hypopituitarism and their manifestation in the neonatal period. Early Hum Dev. 2009;85:705–712. doi:10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2009.08.057

19. Bornstein SR, Allolio B, Arlt W, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of primary adrenal insufficiency: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101:364–389. doi:10.1210/jc.2015-1710

20. Kurtoğlu S, Hatipoğlu N. Non-classical congenital adrenal hyperplasia in childhood. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol. 2017;9(1):1–7. doi:10.4274/jcrpe.3378

21. Livadas S, Bothou C. Management of the female with non-classical congenital adrenal hyperplasia (NCCAH): a patient-oriented approach. Front Endocrinol. 2019;10:366. doi:10.3389/fendo.2019.00366

22. Miller W. Disorders in the initial steps of steroid hormone synthesis. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2017;165:18–37. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2016.03.009

23. Nowaczyk M, Irons M. Smith–Lemli–Opitz syndrome: phenotype, natural history, and epidemiology. Am J Med Genet Part C Semin Med Genet. 2012;160:250–262. doi:10.1002/ajmg.c.31343

24. Anderson R, Byrum R, Coates P, Sando G. Mutations at the lysosomal acid cholesteryl ester hydrolase gene locus in Wolman disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:2718. doi:10.1073/pnas.91.7.2718

25. Jones S, Rojas-Caro S, Quinn A. Survival in infants treated with sebelipase Alfa for lysosomal acid lipase deficiency: an open-label, multicenter, dose-escalation study. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2017;12:25. doi:10.1186/s13023-017-0587-3

26. Muscatelli F, Strom T, Walker A, et al. Mutations in the DAX-1 gene give rise to both X-linked adrenal hypoplasia congenita and hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Nature. 1994;372:672–676. doi:10.1038/372672a0

27. Vilain E, Merrer M, Lecointre C, et al. IMAGe, a new clinical association of Intrauterine growth retardation, metaphyseal dysplasia, adrenal hypoplasia congenita, and Genital anomalies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84(12):4335–4340. doi:10.1210/jcem.84.12.6186

28. Narumi S, Amano N, Ishii T, et al. SAMD9 mutations cause a novel multisystem disorder, MIRAGE syndrome, and are associated with loss of chromosome 7. Nat Genet. 2016;48:792–797. doi:10.1038/ng.3569

29. Maharaj A, Maudhoo A, Chan L, et al. Isolated glucocorticoid deficiency: genetic causes and animal models. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2019;189:73–80. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2019.02.012

30. Metherell L, Chapple J, Cooray S, et al. Mutations in MRAP, encoding a new interacting partner of the ACTH receptor, cause familial glucocorticoid deficiency type 2. Nat Genet. 2005;37:166–170. doi:10.1038/ng1501

31. Prpic I, Huebner A, Persic M, et al. Triple A syndrome: genotype-phenotype assessment. Clin Genet. 2003;63:415. doi:10.1034/j.1399-0004.2003.00070.x

32. Kurnaz E, Duminuco P, Aycan Z, et al. Clinical and genetic characterisation of a series of patients with triple A syndrome. Eur J Pediatr. 2018;177(3):363–369. doi:10.1007/s00431-017-3068-8

33. Brett E, Auchus R. Genetic forms of adrenal insufficiency. Endocr Pract. 2015;21(4):395–399. doi:10.4158/EP14503.RA

34. Prasad R, Hadjidemetriou I, Maharaj A, et al. Sphingosine-1-phosphate lyase mutations cause primary adrenal insufficiency and steroid-resistant nephrotic syndrome. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:942–953. doi:10.1172/JCI90171

35. Moser H, Moser A, Smith K, et al. Adrenoleukodystrophy: phenotypic variability and implications for therapy. J Inherit Metab Dis. 1992;15:645. doi:10.1007/BF01799621

36. Bradbury A, Ream M. Recent advancements in the diagnosis and treatment of leukodystrophies. Semin Pediatr Neurol. 2021;37:100876. doi:10.1016/j.spen.2021.100876

37. Engelen M, Kemp S. X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy: pathogenesis and treatment. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2014;14(10):486. doi:10.1007/s11910-014-0486-0

38. Federico A, de Visser M. New disease modifying therapies for two genetic childhood-onset neurometabolic disorders (metachromatic leucodystrophy and adrenoleucodystrophy). Neurol Sci. 2021;42(7):2603–2606. doi:10.1007/s10072-021-05412-x

39. Artuch R, Pavía C, Playán A, et al. Multiple endocrine involvement in two pediatric patients with Kearns-Sayre syndrome. Horm Res. 1998;50:99. doi:10.1159/000023243

40. Peterson P, Pitkänen J, Sillanpää N, et al. Autoimmune polyendocrinopathy candidiasis ectodermal dystrophy (APECED): a model disease to study molecular aspects of endocrine autoimmunity. Clin Exp Immunol. 2004;135:348. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02384.x

41. Brewer K, Parziale VS, Eisenbarth GS, et al. Screening patients with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus for adrenal insufficiency. New Engl J Med. 1997;337:202. doi:10.1056/NEJM199707173370314

42. Yu L, Brewer K, Gates S, et al. DRB1*04 and DQ alleles: expression of 21-hydroxylase autoantibodies and risk of progression to Addison’s disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:328. doi:10.1210/jcem.84.1.5414

43. Myhre A, Aarsetøy H, Undlien D, et al. High frequency of coeliac disease among patients with autoimmune adrenocortical failure. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:511. doi:10.1080/00365520310002544

44. Elfström P, Montgomery S, Kämpe O, et al. Risk of primary adrenal insufficiency in patients with celiac disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:3595. doi:10.1210/jc.2007-0960

45. Coco G, Dal Pra C, Presotto F, et al. Estimated risk for developing autoimmune Addison’s disease in patients with adrenal cortex autoantibodies. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91(5):1637–1645. doi:10.1210/jc.2005-0860

46. Yamamoto YT. Latent adrenal insufficiency: concept, clues to detection, and diagnosis. Endocr Pract. 2018;24(8):746–755. doi:10.4158/EP-2018-0114

47. Laureti S, De Bellis A, Muccitelli V, et al. Levels of adrenocortical autoantibodies correlate with the degree of adrenal dysfunction in subjects with preclinical Addison’s disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1998;83:3507–3511. doi:10.1210/jcem.83.10.5149

48. Baker P, Nanduri P, Gottlieb P, et al. Predicting the onset of Addison’s disease: ACTH, renin, cortisol and 21-hydroxylase autoantibodies. Clin Endocrinol. 2012;76:617–624. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2265.2011.04276.x

49. Thuillier P, Kerlan V. Subclinical adrenal diseases: silent pheochromocytoma and subclinical Addison’s disease. Ann Endocrinol. 2012;73(Suppl 1):S45–S54. doi:10.1016/S0003-4266(12)70014-8

50. Raverot V, Richet C, Morel Y, Raverot G, Borson-Chazot F. Establishment of revised diagnostic cut-offs for adrenal laboratory investigation using the new Roche Diagnostics Elecsys® Cortisol II assay. Ann Endocrinol. 2016;77(5):620–622. doi:10.1016/j.ando.2016.05.002

51. Grossman A. The diagnosis and management of central hypoadrenalism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:4855e63. doi:10.1210/jc.2010-0982

52. Petersenn S, Quabbe HJ, Schöfl C, et al. The rational use of pituitary stimulation tests. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2010;107(25):437–443. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2010.0437

53. Kline GA, Buse J, Krause RD. Clinical implications for biochemical diagnostic thresholds of adrenal sufficiency using a highly specific cortisol immunoassay. Clin Biochem. 2017;50(9):475–480. doi:10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2017.02.008

54. Agwu JC, Spoudeas H, Hindmarsh PC, Pringle PJ, Brook CGD. Tests of adrenal insufficiency. Arch Dis Child. 1999;80(4):330–333. doi:10.1136/adc.80.4.330

55. Maghnie M, Uga E, Temporini F, et al. Evaluation of adrenal function in patients with growth hormone deficiency and hypothalamic-pituitary disorders: comparison between insulin-induced hypoglycemia, low-dose ACTH, standard ACTH and CRH stimulation tests. Eur J Endocrinol. 2005;152:735–741. doi:10.1530/eje.1.01911

56. Kazlauskaite R, Maghnie M. Pitfalls in the diagnosis of central adrenal insufficiency in children. Endocr Dev. 2010;17:96e107.

57. Chanson P, Guignat L, Goichot B, et al. Group 2: adrenal insufficiency: screening methods and confirmation of diagnosis. Ann Endocrinol. 2017;78:495e511. doi:10.1016/j.ando.2017.10.005

58. Ospina N, Al Nofal A, Bancos I, et al. ACTH stimulation tests for the diagnosis of adrenal insufficiency: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(2):427–434. doi:10.1210/jc.2015-1700

59. Park J, Das U, Didi M, et al. The challenges of cortisol replacement therapy in childhood: observations from a case series of children treated with modified-release hydrocortisone. Pediatr Drugs. 2018;20(6):567–573. doi:10.1007/s40272-018-0306-0

60. Woodcock T, Barker P, Daniel S, et al. Guidelines for the management of glucocorticoids during the peri-operative period for patients with adrenal insuf fi ciency Guidelines from the Association of Anaesthetists, the Royal College of Physicians and the Society for Endocrinology UK. Anaesthesia. 2020;75:654–663. doi:10.1111/anae.14963

61. Rushworth R, Torpy DJ, Falhammar H. Adrenal crisis. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(9):852–861. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1807486

62. Miller BS, Spencer SP, Geffner ME, et al. Emergency management of adrenal insufficiency in children: advocating for treatment options in outpatient and field settings. J Investig Med. 2020;68:16–25. doi:10.1136/jim-2019-000999

This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at

This work is published and licensed by Dove Medical Press Limited. The full terms of this license are available at