Abstract

Background

Thymic neuroendocrine tumor as a cause of Cushing syndrome is extremely rare in children.

Case presentation

We report a case of a 10-year-old girl who presented with typical symptoms and signs of hypercortisolemia, including bone fractures, growth retardation, and kidney stones. The patient was managed with oral ketoconazole, during which she experienced adrenal insufficiency, possibly due to either cyclic adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) secretion or concurrent COVID-19 infection. The patient underwent a diagnostic work-up which indicated the possibility of an ACTH-secreting pituitary neuroendocrine tumor. However, after a transsphenoidal surgery, the diagnosis was not confirmed on histopathological examination. Subsequent bilateral inferior petrosal sinus sampling showed strong indications of the presence of ectopic ACTH syndrome. Detailed rereading of functional imaging studies, including 18F-FDG PET/MRI and 68Ga DOTATOC PET/CT, ultimately identified a small lesion in the thymus. The patient underwent videothoracoscopic thymectomy that confirmed a neuroendocrine tumor with ACTH positivity on histopathological examination.

Conclusion

This case presents some unique challenges related to the diagnosis, management, and treatment of thymic neuroendocrine tumor in a child. We can conclude that ketoconazole treatment was effective in managing hypercortisolemia in our patient. Further, a combination of functional imaging studies can be a useful tool in locating the source of ectopic ACTH secretion. Lastly, in cases of discrepancy in the results of stimulation tests, bilateral inferior petrosal sinus sampling is highly recommended to differentiate between Cushing disease and ectopic ACTH syndrome.

Background

In children above seven years of age, the majority of pediatric Cushing syndrome (CS) cases are caused by a pituitary neuroendocrine tumors (PitNET). However, a differential diagnosis of hypercortisolemia in children is often challenging concerning the interpretation of stimulation tests and the fact that up to 50% of PitNET may not be detected on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [1]. An ectopic adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) syndrome (EAS) is extremely rare in children. Its diagnosis is often missed or confused with Cushing disease (CD) [2]. Most ACTH-secreting tumors originate from bronchial or thymic neuroendocrine tumors (NETs), or less commonly, from NETs in other locations. To diagnose EAS, specific functional imaging studies are often indicated to elucidate the source of ACTH production.

Pharmacotherapy may be used before surgery to control hypercortisolemia and its symptoms/signs, or in patients in whom the source of hypercortisolism has not been found (e.g., EAS), or surgery failed. Ketoconazole or metyrapone, as adrenal steroidogenesis blockers, were found to be very efficient, although they exhibit side effects [3].

Furthermore, cyclic secretion of ACTH followed by fluctuating plasma cortisol levels is extremely rare in children, including those with EAS [4, 5]. Therefore, in cyclic EAS, the use of steroid inhibitors or acute illness or trauma can be associated with adrenal insufficiency, which can be life-threatening. Here we describe the clinical features, laboratory and radiological investigations, results, management, and clinical outcome of a 10-year-old girl with a thymic NET presenting with ACTH secretion.

Case presentation

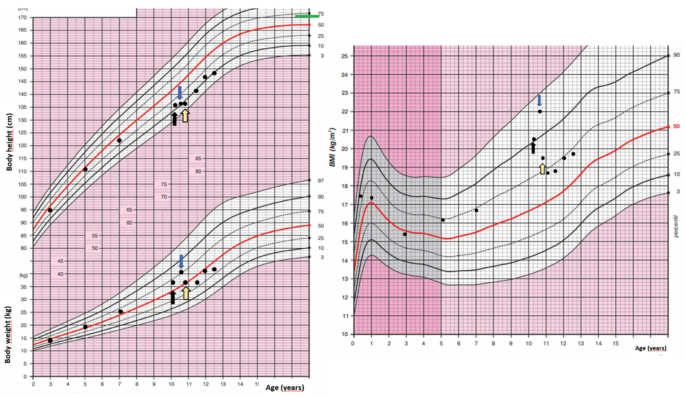

A 10-year-old girl was acutely admitted to our university hospital for evaluation of facial edema and macroscopic hematuria in May 2021. A day before admission, she presented to the emergency room for dysuria, pollakiuria, nausea, and pain in her right lower back. Over the past year she had experienced excessive weight gain with increased appetite and growth retardation (Fig. 1). Her height over three years had shifted from the 34th to the 13th centile (Fig. 1). Her parents noticed facial changes, pubic hair development, increased irritability, and moodiness.

Body weight, body height, and body mass index development of the case patient. The black arrow indicates the first presentation, the blue arrow indicates the start of ketoconazole treatment and the yellow arrow indicates the time of thymectomy. Mid-parental height is indicated by the green line

At admission, she was found to have a moon face with a plethora, few acne spots on forehead, as well as facial puffiness. In contrast to slim extremities, an abnormal fat accumulation was observed in the abdomen. Purple striae were present on abdomen and thighs. She did not present with any bruising, proximal myopathy, or edema. On physical examination, she was prepubertal, height was 135 cm (13th centile), and weight was 37 kg (69th centile) with a BMI of 20.4 kg/m2 (90th centile). She developed persistent hypertension. Her past medical history was uneventful except for two fractures of her upper left extremity after minimal trips one and three years ago, both treated with a caste. Apart from hypothyroidism on the maternal side, there was no history of endocrine abnormalities or tumors in the family.

In the emergency room, the patient was started on sulfonamide, pain medication, and intravenous (IV) fluids. Her hypertensive crises were treated orally with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or with a combination of adrenergic antagonists and serotonin agonists administered IV. Hypokalemia had initially been treated with IV infusion and then with oral potassium supplements. A low serum phosphate concentration required IV management. The initial investigation carried out in the emergency room found hematuria with trace proteinuria. Kidney ultrasound showed a 5 mm stone in her right ureter with a 20 mm hydronephrosis. She did not pass any kidney stones, however, fine white sand urine analysis reported 100% brushite stone.

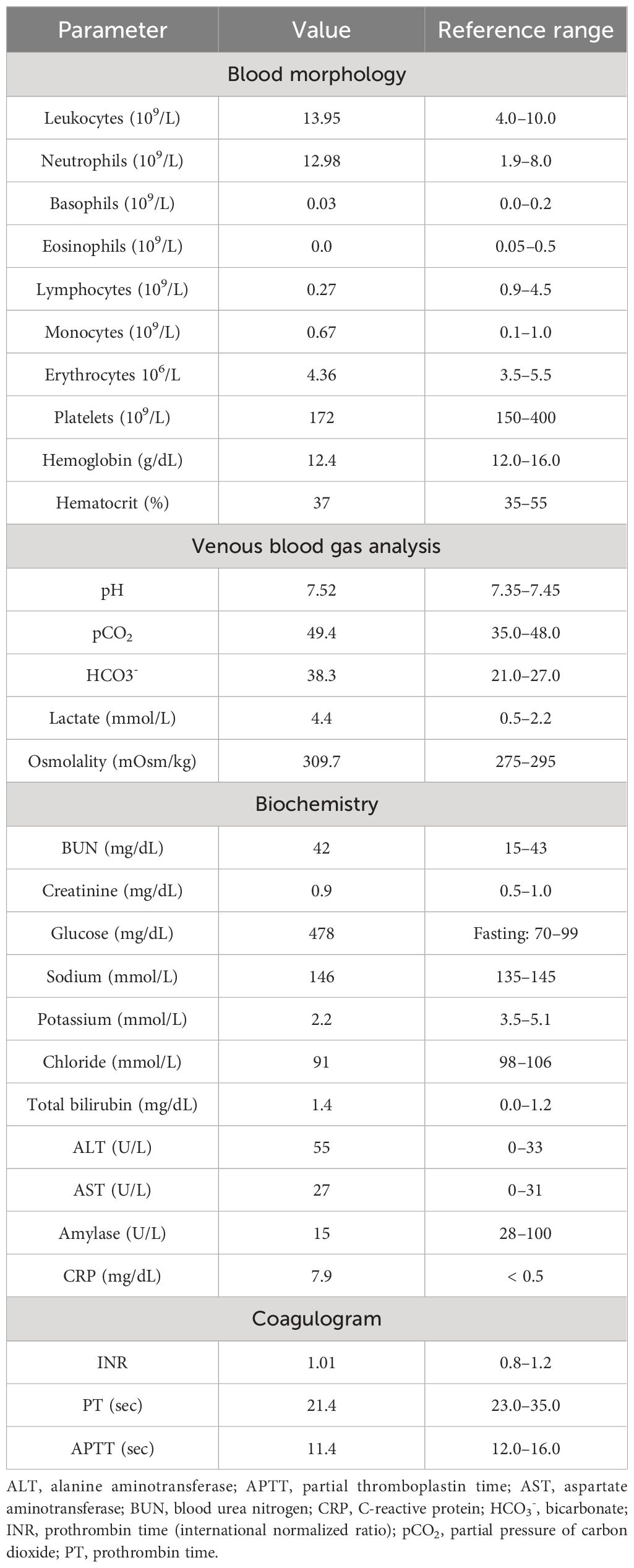

Hypercortisolemia was confirmed by repeatedly increased 24-hour urinary free cortisol (UFC), (5011.9 nmol/day, normal range 79.0-590.0 nmol/day). Her midnight cortisol levels were elevated (961 nmol/l, normal range 68.2–537 nmol/l). There was no suppression of serum cortisol after 1 mg overnight dexamethasone suppression test (DST) or after low-dose DST (LDDST). An increased morning plasma ACTH (30.9 pmol/l, normal range 1.6–13.9 pmol/) suggested ACTH-dependent hypercortisolemia. There was no evidence of a PitNET on a 1T contrast-enhanced MRI. The high-dose DST (HDDST) did not induce cortisol suppression (cortisol 1112 nmol/l at 23:00, cortisol 1338 nmol/l at 8:00). Apart from the kidney stone, a contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) of her neck, chest, and abdomen/pelvis did not detect any lesion. Various tumor markers were negative and the concentration of chromogranin A was also normal.

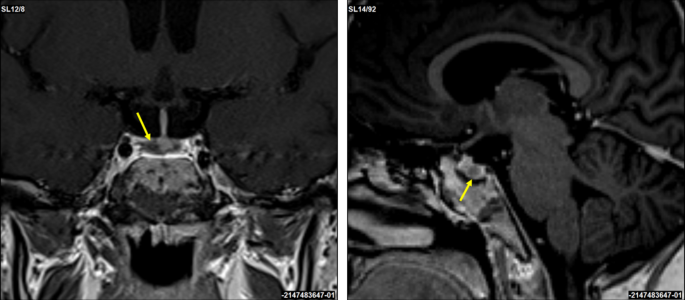

A corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) stimulation test induced an increase in serum cortisol by 32% at 30 min and ACTH concentration by 67% at 15 min (Table 1). A 3T contrast-enhanced MRI scan of the brain identified a 3 × 2 mm lesion in the lateral right side of the pituitary gland (Fig. 2). An investigation of other pituitary hormones was unremarkable. Apart from low serum potassium (minimal level of 2.8 mmol/l; normal range 3.3–4.7 mmol/l) and phosphate (0.94 mmol/l; normal range 1.28–1.82 mmol/l) concentrations, electrolytes were normal. The bone mineral density assessed by whole dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry was normal.

Coronal and sagittal 3T contrast-enhanced brain MRI scans. A suspected 3 × 2 mm lesion in the lateral right side of the pituitary gland (yellow arrows)

The patient was presented at the multidisciplinary tumor board and it was decided that she undergoes transsphenoidal surgery for the pituitary lesion. No PitNET was detected on histopathological examination and no favorable biochemical changes were noted after surgery. After the patient recovered from surgery, subsequent bilateral inferior petrosal sinus sampling (BIPSS) confirmed EAS as the maximum ratio of central to peripheral ACTH concentrations was only 1.7. During the investigation for tumor localization, she was started on ketoconazole treatment (300 mg/day) to alleviate symptoms and signs of hypercortisolism. Treatment with ketoconazole had a beneficial effect on patient health (Fig. 1). There was a weight loss of 2 kg in a month, a disappearance of facial plethora, and a decrease in vigorous appetite. Her liver function tests remained within the normal range.

The 24-hour UFC excretion normalized three weeks after ketoconazole initiation. However, six weeks after continuing ketoconazole therapy (400 mg/day), the patient complained of nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. She was found to have adrenal insufficiency with a low morning serum cortisol of 10.70 nmol/l (normal range 68.2–537 nmol/l) and salivary cortisol concentrations < 1.5 nmol/l (normal range 1.7–29 nmol/l). She was also found to be positive for COVID-19 infection. Ketoconazole treatment was stopped and our patient was educated to take stress steroids in case of persisting or worsening symptoms. Her clinical status gradually improved and steroids were not required.

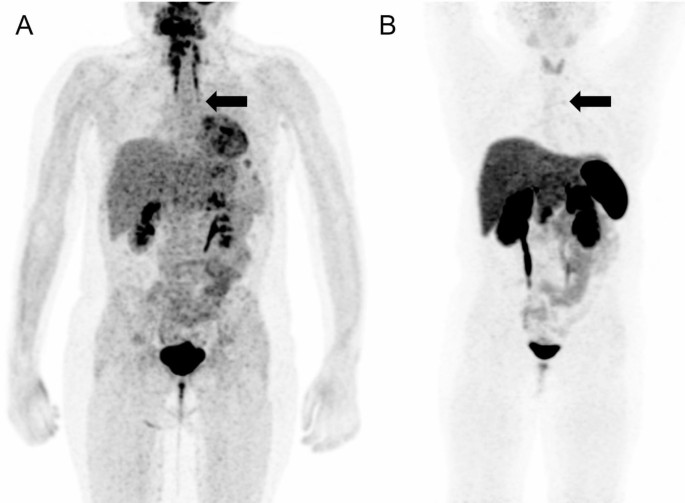

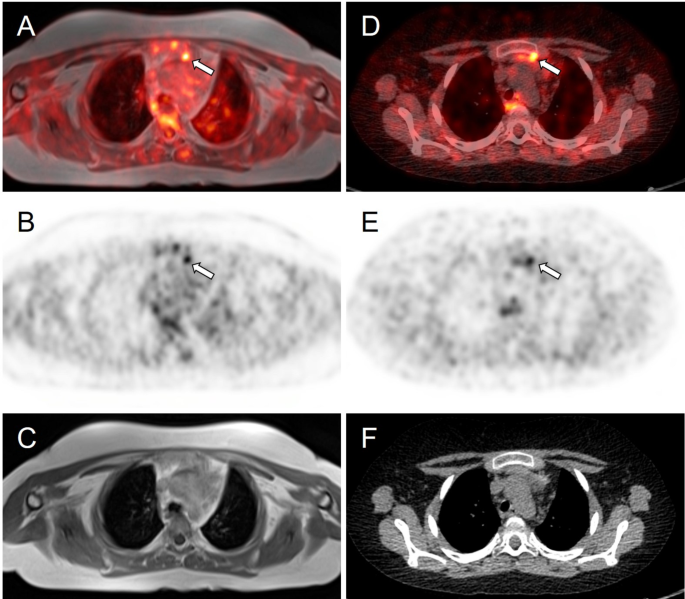

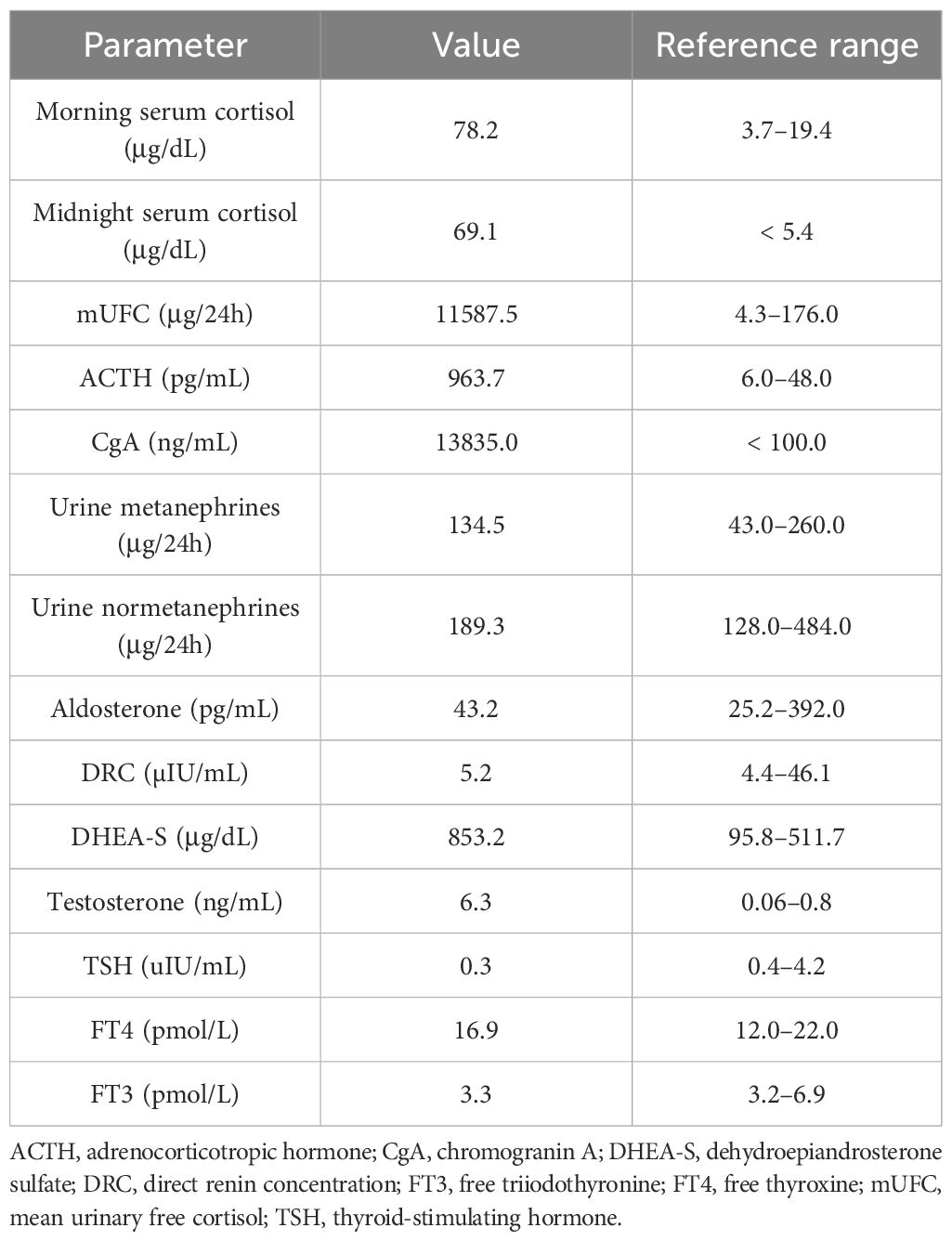

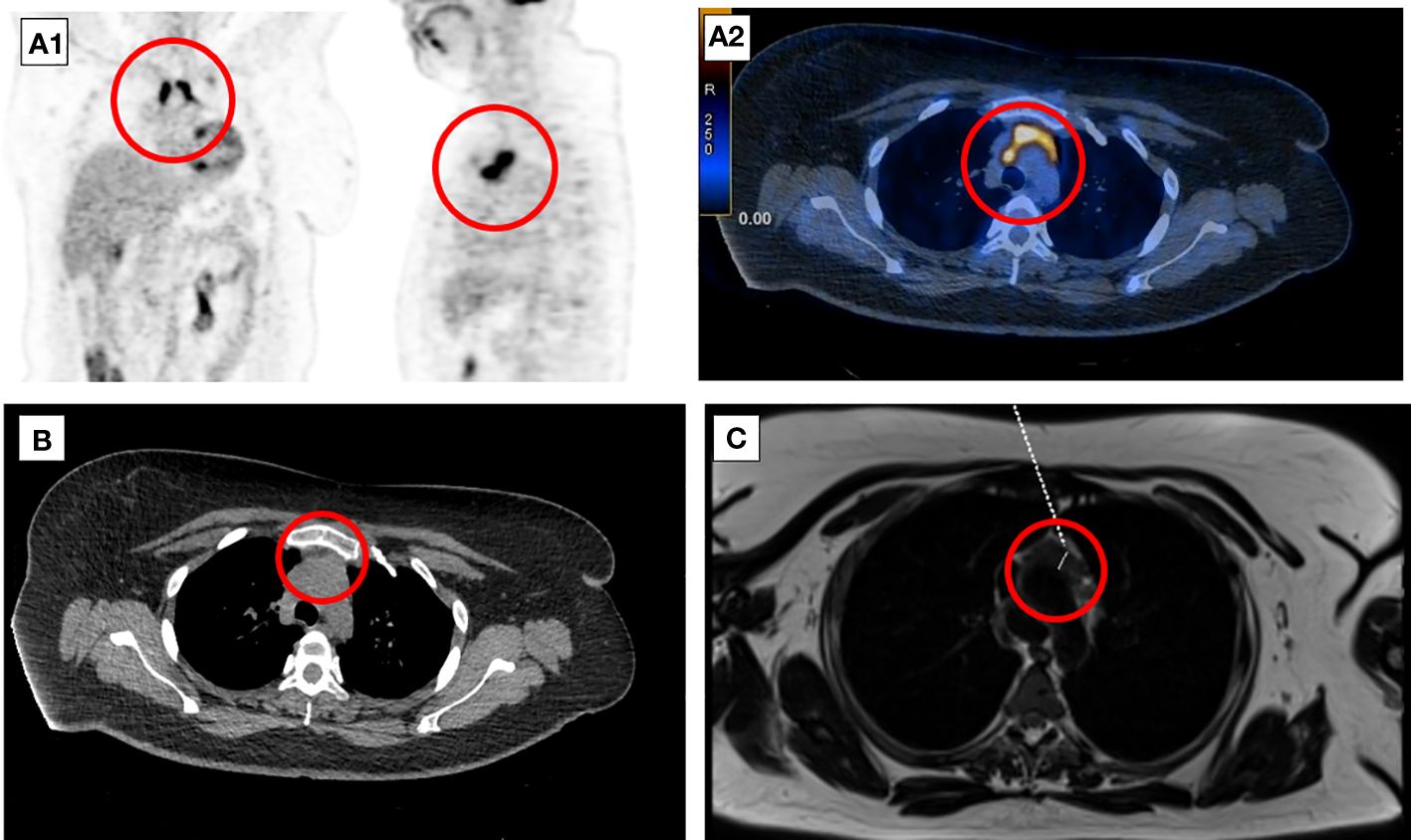

Meanwhile, whole-body fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (18F-FDG PET)/MRI was performed with no obvious hypermetabolic lesion suspicious of a tumor. No obvious accumulation was detected on 68Ga-DOTATOC PET/CT images (Fig. 3). However, a subsequent careful and detailed re-review of the images detected a discrete lesion on 18F-FDG PET/MRI and 68Ga-DOTATOC PET/CT scans in the left anterior mediastinum, in the thymus (Fig. 4).

18F-FDG PET/MRI (A) and 68Ga-DOTATOC (B) PET/CT scans. Whole body MIP reconstructions. Subtle correspondent focal hyperactivity in the left mediastinum (black arrow). The 18F-FDG PET/MRI image courtesy of Prof. Jiri Ferda, MD, PhD, Clinic of the Imaging Methods, University Hospital Plzen, Czech Republic

Axial slices of PET/MRI (A–C) and 68Ga-DOTATOC (D–F) PET/CT scans. Subtle correspondent focal hyperactivity in the left mediastinum (white arrow). No obvious finding on MRI (C) and CT (F) scans. The FDG PET/MRI image courtesy of Prof. Jiri Ferda, MD, PhD, Clinic of the Imaging Methods, University Hospital Plzen, Czech Republic

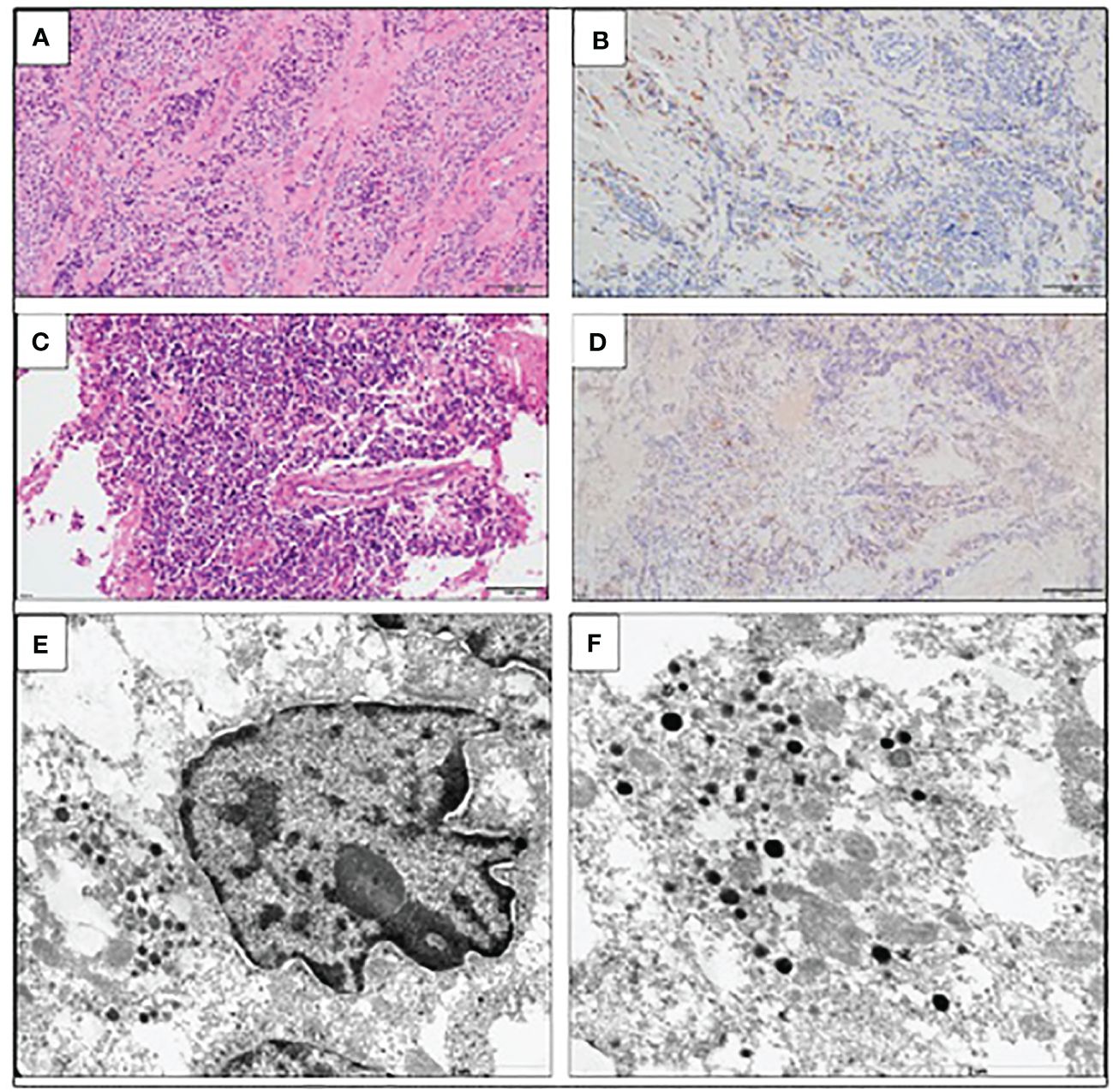

Three weeks after the episode of adrenal insufficiency and being off ketoconazole treatment, our patient´s pre-surgery laboratory tests showed slightly low morning cortisol 132 nmol/l with surprisingly normal ACTH 2.96 pmol/l (normal range 1.6–13.9 pmol/). Given the upcoming surgery, she was initiated on a maintenance dose of hydrocortisone (15 mg daily = 12.5 mg/m2/day). Further improvement of cushingoid characteristics (improvement of facial plethora and moon face, weight loss) was noticed. Our patient underwent videothoracoscopic surgery, and a hyperplastic thymus of 80 × 70 × 15 mm with a 4 mm nodule was successfully removed. Tumor immunohistochemistry was positive for ACTH, chromogranin A, CD56, and synaptophysin. Histopathological findings were consistent with a well-differentiated NET grade 1. A subsequent genetic screening did not detect any pathogenic variant in the MEN1 gene.

After surgery, hydrocortisone was switched to a stress dose and gradually decreased to a maintenance dose. Antihypertensive medication was stopped and further weight loss was observed after thymectomy. Within a few weeks after the thoracic surgery, the patient entered puberty, her mood improved significantly, and potassium supplements were stopped. Finally, hydrocortisone treatment was stopped ten months after thymectomy.

Discussion and conclusions

The case presented here demonstrates a particularly challenging work-up of the pediatric patient with the diagnosis of CS caused by EAS due to thymic NET. Differentiating CD and EAS can sometimes be difficult, including the use of various laboratory and stimulation tests and their interpretation, as well as proper, often challenging, reading of functional imaging modalities, especially if a discrete lesion is present at an unusual location [1]. When using established criteria for Cushing disease (for the CRH test an increase of cortisol and/or ACTH by ≥ 20% or ≥ 35%, respectively, and a ≥ 50% suppression of cortisol for the HDDST) our patient presented discordant results. The CRH stimulation test induced an increase in cortisol by 32% and ACTH by 67% and the 3T MRI pointed to the right-side pituitary lesion, both to yield false positive results. The HDDST, on the other hand, did not induce cortisol suppression and was against characteristic findings for CD. We did not proceed with desmopressin testing, which also induces an excess ACTH and cortisol response in CD patients and has rarely been used in pediatric patients, except in those with extremely difficult venous access [6]. Recently published articles investigated the reliability of CRH stimulation tests and HDDST and both concluded that the CRH test has greater specificity than HDDST [7, 8]. Elenius et al. suggested optimal response criteria as a ≥ 40% increase of ACTH and/or cortisol (cortisol as the most specific measure of CD) during the CRH test and a ≥ 69% suppression of serum cortisol during HDDST [7]. Using these criteria, the CD would be excluded in our patient. To demonstrate that the proposed thresholds for the test interpretation widely differ, Detomas et al. proposed a ≥ 12% cortisol increase and ≥ 31% ACTH increase during the CRH test to confirm CD [8].

The fact that up to 50% of PitNET may not be detected on MRI [1] and that more than 20% of patients with EAS are reported to have pituitary incidentalomas [9] makes MRI somewhat unreliable in differentiating CD and EAS. However, finally, well-established and generally reliable BIPSS in our patient supported the diagnosis of EAS. Thus, BIPSS is considered a gold standard to differentiate between CD and EAS; however, it can still provide false negative results in cyclic CS if performed in the trough phase [10] or in vascular anomalies or false positive results as in a recent case of orbital EAS [11].

In children, the presence of thymus tissue may be misinterpreted as normal. Among other reports of thymic NET [12], Hanson et al. reported a case of a prepubertal boy in whom a small thymic NET was initially treated as normal thymus tissue on CT [13]. In our case, initially, the lesion was not detected on the 18F-FDG and 68Ga-DOTATOC PET scans. A small thymic NET was visible only after a detailed and careful re-reading of both PET scans. Although somatostatin receptor (SSR) PET imaging may be helpful in identifying ectopic CRH- or ACTH-producing tumors, there are still some limitations [13]. For example, in the study by Wannachalee et al., 68Ga-DOTATATE identified suspected primary lesions causing ECS in 65% of patients with previously occult tumors and was therefore concluded as a sensitive method for primary as well as metastatic tumors [14]. In our patient, the final correct diagnosis was based on the results of both PET scans. This is in full support of the article published by Liu et al. who concluded that 18F-FDG and SSR PET scans are complementary in determining the proper localization of ectopic ACTH production [15]. Additionally, it is worth noting that not all NETs stain positively for ACTH which may present a burden in its identification.

To control hypercortisolemia, both ketoconazole and metyrapone were considered in our patient. Due to the side effects of metyrapone on blood pressure, ketoconazole was started as a preferred option in our pediatric patient. A retrospective multicenter study concluded that ketoconazole treatment is effective with acceptable side effects, with no fatal hepatitis and adrenal insufficiency in 5.4% of patients [3]. During ketoconazole treatment, our patient developed adrenal insufficiency; however, it is impossible to conclude whether this was solely due to ketoconazole treatment or whether an ongoing COVID-19 infection contributed to the adrenal insufficiency or whether this was caused by a phase of lower or no ACTH secretion from the tumor often seen in patients with cyclic ACTH secretion. The patient’s cyclic ACTH secretion is highly probable since her morning cortisol was slightly lower and ACTH was normal, even after being off ketoconazole treatment for 3 weeks.

When retrospectively and carefully reviewing all approaches to the diagnostic and management care of our pediatric patient, it would be essential to proceed to BIPSS before any pituitary surgery, especially when obtaining discrepant results from stimulation tests, as well as detecting a discrete pituitary lesion (≤ 6 mm) as recommended by the current guidelines [16]. This was our first experience using ketoconazole in a young child, and although this treatment was associated with very good outcomes in treating hypercortisolemia, close monitoring, and family education on signs and symptoms of adrenal insufficiency are essential to recognizing adrenal insufficiency promptly in any patient with EAS, especially those presenting also with some other comorbidities or stress, here COVID-19 infection.

In conclusion, the pediatric patient here presenting with EAS caused by thymic NET needs very careful assessment including whether cyclic CS is present, the outline of a good management plan to use all tests appropriately and in the correct sequence, monitoring carefully for any signs or symptoms of adrenal insufficiency, and apply appropriate imaging studies, with experienced radiologists providing accurate readings. Furthermore, ketoconazole treatment was found to be effective in reducing the symptoms and signs of CS in this pediatric patient. Finally, due to the rarity of this disease and the challenging work-up, we suggest that a multidisciplinary team of experienced physicians in CS management is highly recommended.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Abbreviations

- ACTH:

- Adrenocorticotrophic hormone

- BIPSS:

- Bilateral inferior petrosal sinus sampling

- CD:

- Cushing disease

- CRH:

- Corticotropin-releasing hormone

- CS:

- Cushing syndrome

- CT:

- Computed tomography

- DST:

- Dexamethasone suppression test

- EAS:

- Ectopic adrenocorticotropic hormone syndrome

- 18F-FDG PET:

- Fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography

- HDDST:

- High-dose dexamethasone suppression test

- IV:

- Intravenous

- LDDST:

- Low-dose dexamethasone suppression test

- NET:

- Neuroendocrine tumor

- PitNET:

- Pituitary neuroendocrine tumor

- UFC:

- Urinary free cortisol

References

-

Streuli R. A rare case of an ACTH/CRH co-secreting midgut neuroendocrine tumor mimicking Cushing’s disease. Endocrinol Diabetes Metab Case Rep. 2017;2017:17–58. ,Krull I, Brändle M, et al.

-

Karageorgiadis AS, Papadakis GZ, Biro J, et al. Ectopic adrenocorticotropic hormone and corticotropin-releasing hormone co-secreting tumors in children and adolescents causing cushing syndrome: a diagnostic dilemma and how to solve it. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(1):141–8.

-

Castinetti F, Guignat L, Giraud P, et al. Ketoconazole in Cushing’s disease: is it worth a try? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2014;99(5):1623–30.

-

Mi Q, Yin M-Z, Gao Y-J et al. Thymic atypical carcinoid with cyclical Cushing’s syndrome in a 7-year-old boy: a case report and review of the literature. Intern Med. 2014;4(5).

-

Moszczyńska E, Pasternak-Pietrzak K, Prokop-Piotrkowska M, et al. Ectopic ACTH production by thymic and appendiceal neuroendocrine tumors – two case reports. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2020;34(1):141–6.

-

Crock PA, Ludecke DK, Knappe UJ, et al. A personal series of 100 children operated for Cushing’s disease (CD): optimizing minimally invasive diagnosis and transnasal surgery to achieve nearly 100% remission including reoperations. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2018;31(9):1023–31.

-

Elenius H, McGlotten R, Nieman LK. Ovine CRH stimulation and 8 mg dexamethasone suppression tests in 323 patients with ACTH-dependent Cushing’s syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2023;109(1):e189–189.

-

Detomas M, Ritzel K, Nasi-Kordhishti I, et al. Outcome of CRH stimulation test and overnight 8 mg dexamethasone suppression test in 469 patients with ACTH-dependent Cushing’s syndrome. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:955945.

-

Yogi-Morren D, Habra MA, Faiman C, et al. Pituitary MRI findings in patients with pituitary and ectopic ACTH-dependent Cushing syndrome: does a 6-mm pituitary tumor size cut-off value exclude ectopic ACTH syndrome? Endocr Pract. 2015;21(10):1098–103.

-

Albani A, Berr CM, Beuschlein F, et al. A pitfall of bilateral inferior petrosal sinus sampling in cyclic Cushing’s syndrome. BMC Endocr Disord. 2019;19(1):105.

-

Tan H, Chen D, Yu Y, et al. Unusual ectopic ACTH syndrome in a patient with orbital neuroendocrine tumor, resulted false-positive outcome of BIPSS: a case report. BMC Endocr Disord. 2020;20(1):116.

-

Ahmed MF, Ahmed S, Abdussalam A, et al. A rare case of ectopic adrenocorticotropic hormone syndrome (EAS) in an adolescent girl with a thymic neuroendocrine tumour. Cureus. 2024;16(8):e66615.

-

Hanson JA, Sohaib SA, Newell-Price J, et al. Computed tomography appearance of the thymus and anterior mediastinum in active Cushing’s syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999;84:602–5.

-

Wannachalee T, Turcu AF, Bancos I, et al. The clinical impact of [68 Ga]-DOTATATE PET/CT for the diagnosis and management of ectopic adrenocorticotropic hormone – secreting Tumours. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2019;91(2):288–94.

-

Liu Q, Zang J, Yang Y, et al. Head-to-head comparison of 68Ga-DOTATATE PET/CT and 18F-FDG PET/CT in localizing tumors with ectopic adrenocorticotropic hormone secretion: a prospective study. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2021;48(13):4386–95.

-

Flesiriu M, Auchus R, Bancos I, et al. Consensus on diagnosis and management of Cushing’s disease: a guideline update. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021;9(12):847–75.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all the colleagues from the Thomayer University Hospital and Military University Hospital who were involved in the inpatient care of this patient.

Funding

This work was supported by the Charles University research program Cooperatio Pediatrics, Charles University, Third Faculty of Medicine, Prague.

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Signed informed consent was obtained from the patient and the patient´s parents for the publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Filed under: Cushing's, Rare Diseases, symptoms, Treatments | Tagged: Adrenocorticotropic hormone, child, ectopic, female, ketoconazole, thymic tumor | Leave a comment »