Hanna Pierce didn’t expect to learn she had a tumor on her adrenal gland during a CT scan. Just two weeks after delivering her second child and recovering from COVID-19, she went to urgent care with concerns about a possible blood clot. Instead, imaging revealed a tumor in her adrenal gland. “I didn’t have symptoms,” she said. “They were checking for something else and just happened to find it.”

That unexpected discovery in 2021 launched Pierce into a years-long journey that ultimately led to robotic surgery at Baylor Medicine with Dr. Feibi Zheng, an endocrine surgeon who specializes in treating adrenal tumors.

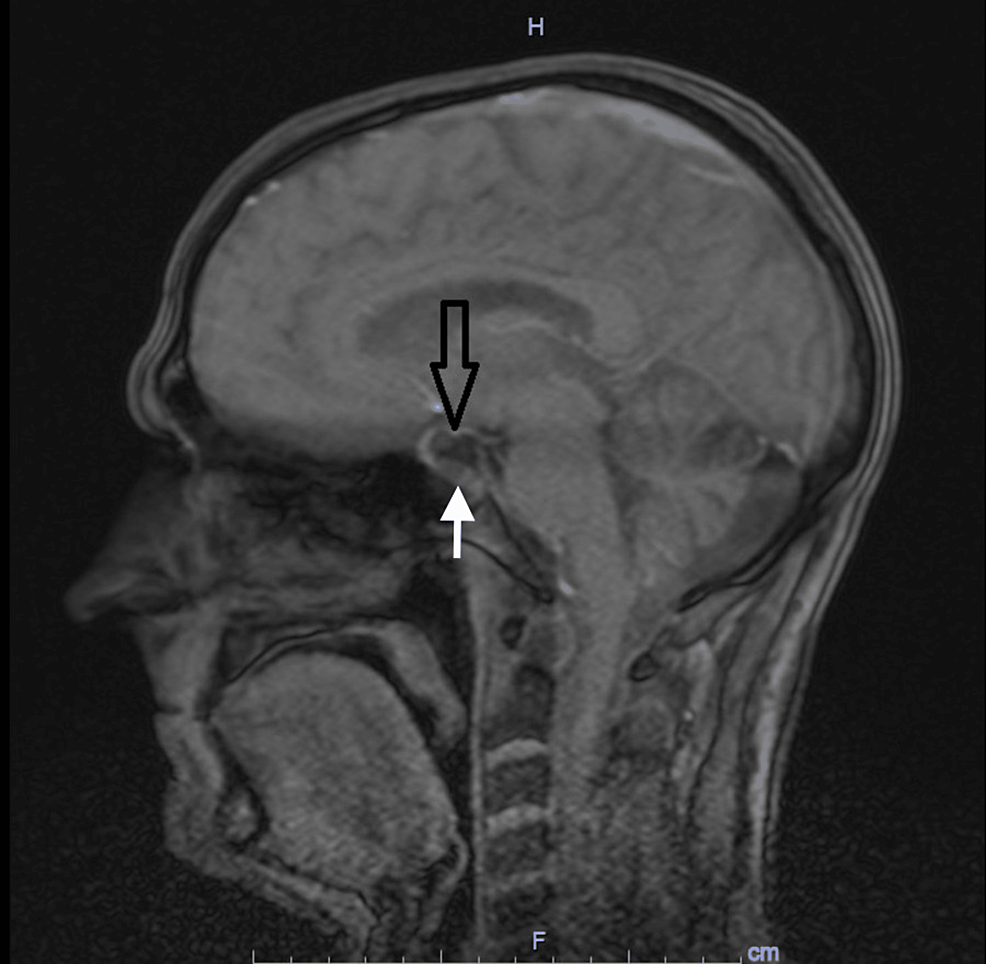

“Many people haven’t heard much about the adrenal glands,” said Zheng, assistant professor in the Division of Surgical Oncology. “They sit on top of the kidneys and produce hormones like cortisol that regulate everything from metabolism to the body’s stress response. If a tumor is overproducing cortisol, it can silently wreak havoc on the body over time.”

Doctors told Pierce that her tumor was consistently producing slightly elevated cortisol, a red flag. “My doctor told me if we left it alone, it could develop into diabetes or full-blown Cushing’s syndrome. At first, we just monitored it,” she said.

In the months and years that followed, Pierce did experience symptoms but attributed them to the demands of motherhood. “After my second child, I couldn’t lose weight no matter what I did. I had anxiety, constant fatigue in the afternoons, and I wasn’t sleeping well,” she recalled. “But I just chalked it up to being a mom of two.”

By 2024, her endocrinologist said it was time to act and referred her to Zheng, who confirmed the tumor was still producing excess cortisol. “Dr. Zheng told me I was going to feel so much better and explained what she was going to do,” Pierce said. “When I went to see her for the consultation, she was very informative. She didn’t pressure me to have surgery but explained everything to me.”

The Baylor Medicine endocrine surgery team, including Zheng and supported by physician assistant Holly Clayton, provided a seamless and collaborative care experience. “Our team-based model allows for better coordination and patient support,” said Clayton, who helped manage Pierce’s preoperative workup and performed her postop visit via telemedicine. “It was clear she wanted answers and a plan, and we were glad to be able to guide her through this process together.”

Zheng performed the adrenalectomy robotically, using a posterior approach — an advanced technique that involves going through the back instead of the front of the abdomen. “It’s a less common approach, but for the right patients, it can reduce pain and speed up recovery,” Zheng said.

Pierce said she felt calm going into the procedure. “Usually, I have white coat syndrome and feel anxious, but this time I didn’t. Everyone gave me step-by-step instructions, and Dr. Zheng explained everything clearly. I really felt like I was in good hands.”

Within a week or two of her June surgery, Pierce noticed changes. “I dropped four pounds almost immediately,” she said. “My face wasn’t as puffy. I felt less anxious and more like myself. Even though I was still recovering, I had more energy, and my body felt like it had reset.”

“Surgery to correct cortisol-producing tumors can make a major difference in quality of life, even if patients don’t meet the full criteria for a Cushing’s diagnosis,” Zheng said. “Mrs. Pierce’s case is a perfect example. She didn’t feel well, but she didn’t know why. Her endocrinologist saw [that] her metabolic parameters were getting worse. Now that the tumor is gone, her symptoms are improving, and her health trajectory is back on track.”

Just a month after surgery, Pierce says she has more energy and is continuing to lose weight. She’s relieved that a straightforward procedure made such a noticeable difference in how she feels.

From https://blogs.bcm.edu/2025/07/23/patient-finds-relief-after-adrenal-gland-tumor-removed/

Filed under: adrenal, Cushing's, Treatments | Tagged: adrenal gland tumor, adrenalectomy, Baylor, cortisol, Division of Surgical Oncology, Dr. Feibi Zheng, endocrine surgeon, endocrine surgery, robotic surgery, surgeon, telemedicine, weight loss | Leave a comment »

View Full Size

View Full Size View Full Size

View Full Size