A diagnostic technique called bilateral inferior petrosal sinus sampling (BIPSS), which measures the levels of the adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) produced by the pituitary gland, should only be used to diagnose cyclic Cushing’s syndrome patients during periods of cortisol excess, a case report shows.

When it is used during a spontaneous remission period of cycling Cushing’s syndrome, this kind of sampling can lead to false results, the researchers found.

The study, “A pitfall of bilateral inferior petrosal sinus sampling in cyclic Cushing’s syndrome,” was published in BMC Endocrine Disorders.

Cushing’s syndrome is caused by abnormally high levels of the hormone cortisol. This is most often the result of a tumor on the pituitary gland that produces too much ACTH, which tells the adrenal glands to increase cortisol secretion.

However, the disease may also occur due to adrenal tumors or tumors elsewhere in the body that also produce excess ACTH — referred to as ectopic Cushing’s syndrome.

Because treatment strategies differ, doctors need to determine the root cause of the condition before deciding which treatment to choose.

BIPSS can be useful in this regard. It is considered a gold standard diagnostic tool to determine whether ACTH is being produced and released by the pituitary gland or by an ectopic tumor.

However, in people with cycling Cushing’s syndrome, this technique might not be foolproof.

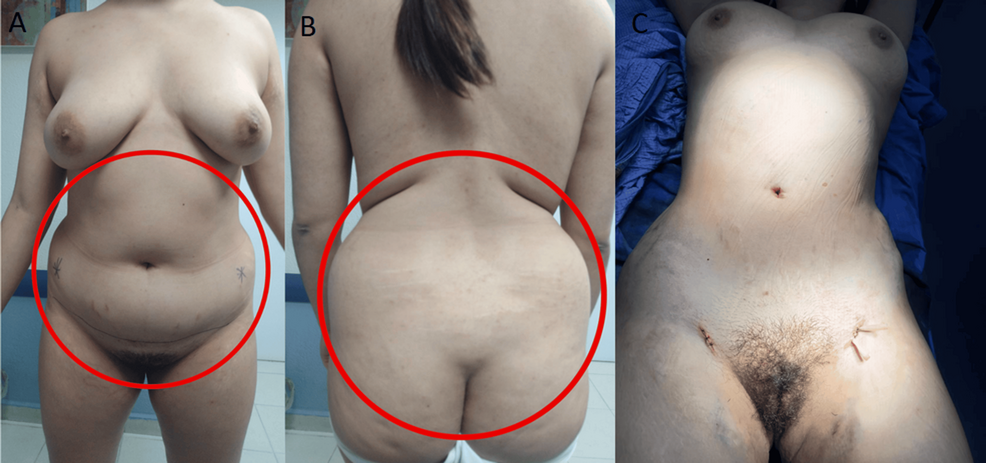

Researchers reported the case of a 43-year-old woman who had rapidly cycling Cushing’s syndrome, meaning she had periods of excess cortisol with Cushing’s syndrome symptoms — low potassium, high blood pressure, and weight gain — followed by normal cortisol levels where symptoms resolved spontaneously.

In general, the length of each period can vary anywhere from a few hours to several months; in the case of this woman, they alternated relatively rapidly — over the course of weeks.

After conducting a series of blood tests and physical exams, researchers suspected of Cushing’s syndrome caused by an ACTH-producing tumor.

The patient eventually was diagnosed with ectopic Cushing’s disease, but a BIPSS sampling performed during a spontaneous remission period led to an initial false diagnosis of pituitary Cushing’s. As a result, the woman underwent an unnecessary exploratory pituitary surgery that revealed no tumor on the pituitary.

Additional imaging studies then identified a few metastatic lesions, some of which were removed surgically, as the likely source of ACTH. However, the primary tumor still hasn’t been definitively identified. At the time of publication, the patient was still being treated for Cushing’s-related symptoms and receiving chemotherapy.

There is still a question of why the initial BIPSS result was a false positive. The researchers think that the likely explanation is that BIPSS was performed during an “off phase,” when cortisol levels were comparatively low. In fact, a later BIPSS performed during a period of high cortisol levels showed no evidence of ACTH excess in the pituitary.

This case “demonstrates the importance of performing diagnostic tests only during the phases of active cortisol secretion, as soon as first symptoms appear,” the researchers concluded.

Filed under: Cushing's, Diagnostic Testing, pituitary, symptoms, Treatments | Tagged: ACTH, Adrenocorticotropic hormone, Bilateral inferior petrosal sinus sampling, BIPSS, Cyclical Cushing's, ectopic | Leave a comment »