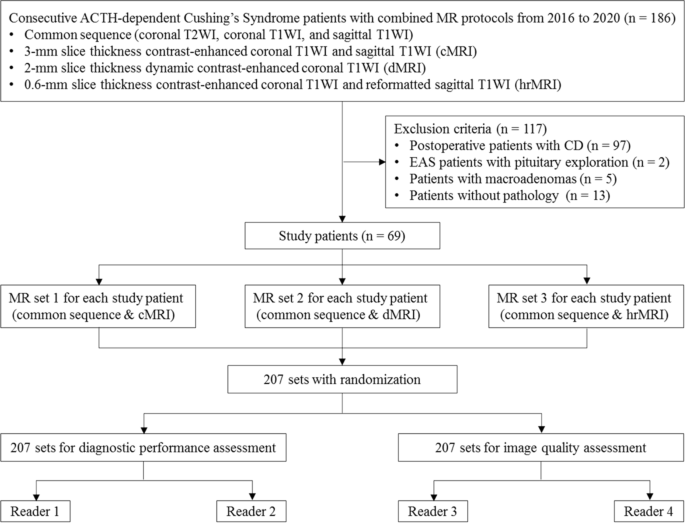

The identification of pituitary microadenomas is considerably challenging but critical in patients with ACTH-dependent Cushing’s syndrome. Our study demonstrated that hrMRI with 3D FSE sequence had higher diagnostic performance (AUC, 0.95–0.97) than cMRI (AUC, 0.74–0.75; p ≤ 0.002) and dMRI (AUC, 0.59–0.68; p ≤ 0.001) for identifying pituitary microadenomas. To our knowledge, there are no previous studies specifically evaluating the identification of pituitary microadenomas on hrMRI with 3D FSE sequence by comparison with cMRI and dMRI in patients with ACTH-dependent Cushing’s syndrome, and this is the largest study conducted in ACTH-secreting microadenomas with a sensitivity of more than 90%.

Recently, techniques for pituitary evaluation have developed rapidly. Because of false negatives and false positives on cMRI and dMRI using 2D FSE sequence [7, 9, 10], a 3D SPGR sequence was introduced for identifying pituitary adenomas. Previous studies demonstrated that the 3D SPGR sequence performed better than the 2D FSE sequence in the identification of pituitary adenomas with a sensitivity of up to 80% [11,12,13]. In patients with hyperprolactinemia, the 3D FSE sequence was recommended [14] and the 3D FSE sequence has rapidly developed recently with superior image quality [15, 16], suggesting that the 3D FSE sequence may be a reliable alternative for identifying pituitary adenomas. However, to our knowledge, few studies have investigated the diagnostic performance of the 3D FSE sequence for identifying ACTH-secreting pituitary adenomas. To fill the gaps, we conducted the current study and revealed that images obtained with the 3D FSE sequence had higher sensitivity (90–93%) in identifying pituitary microadenomas, than that in previous studies using the 3D SPGR sequence [8, 11,12,13].

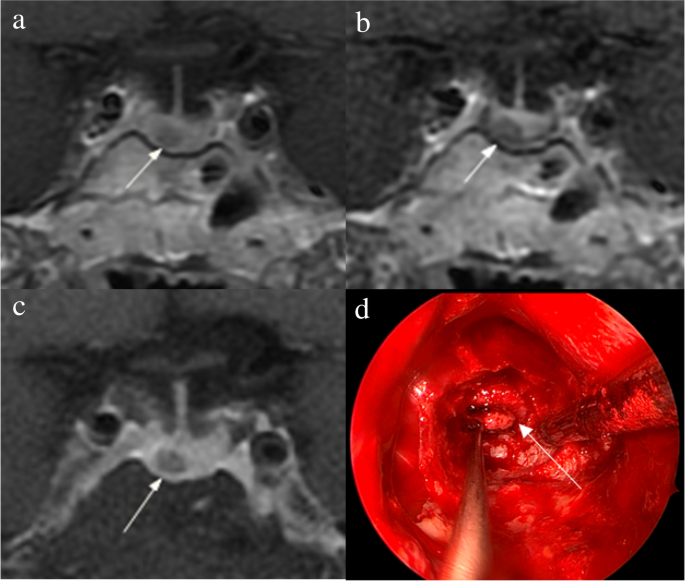

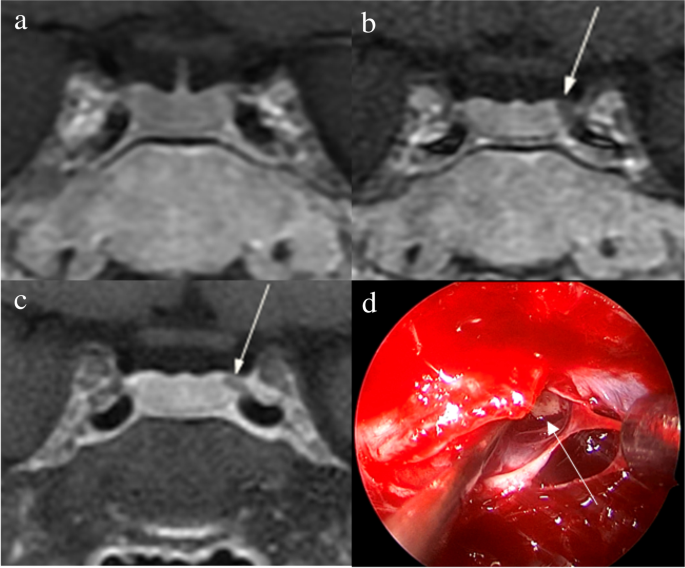

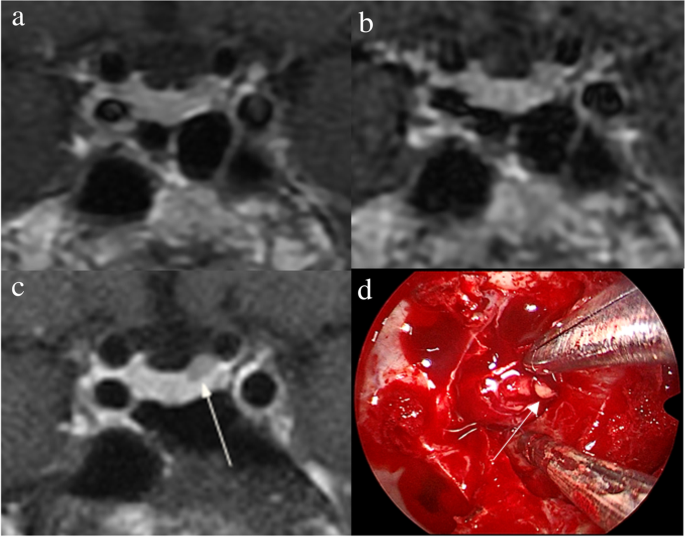

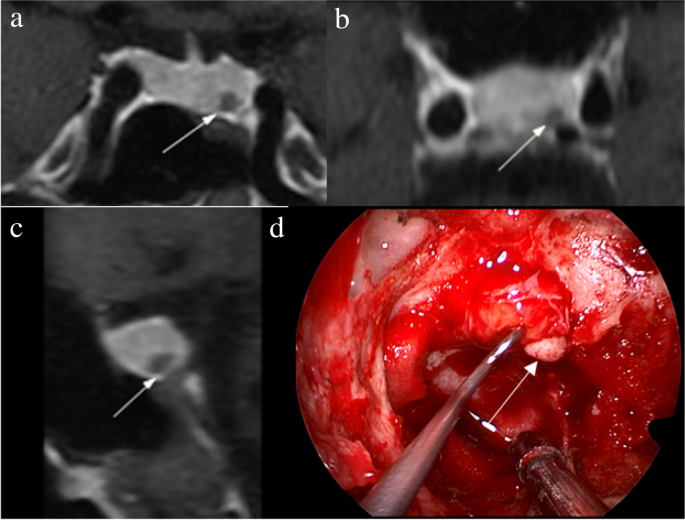

There is a trade-off between spatial resolution and image noise. The reduced slice thickness can overcome the partial volume averaging effect, but it is associated with increased image noise [17]. Strikingly, our study showed that hrMRI had higher image quality scores than cMRI and dMRI, in terms of overall image quality, sharpness, and structural conspicuity. The SNR of the pituitary microadenomas on cMRI was slightly higher than that on hrMRI in our study. This is because the SNR was calculated as the mean signal intensity of the pituitary gland (instead of the pituitary microadenoma) divided by noise when no microadenoma was identified, and the mean signal intensity of the pituitary gland is higher than that of the pituitary microadenoma. About 40% of pituitary microadenomas were missed on cMRI, whereas less than 10% of pituitary microadenomas were missed on hrMRI. Given the situation mentioned above, the SNR on hrMRI was lower than that on cMRI. However, the CNR on hrMRI was significantly higher than that on cMRI and dMRI. Therefore, hrMRI in our study can dramatically improve the spatial resolution with high CNR, enabling the better identification of pituitary microadenomas.

The identification of pituitary adenomas on preoperative MRI in patients with ACTH-dependent Cushing’s syndrome could help the differential diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome and aids surgical resection of lesions. It should be noted that most of the pituitary adenomas in patients with Cushing’s disease are microadenomas [5, 6]. In our study, all the tumors are microadenomas with a median diameter of 5 mm (IQR, 4–5 mm), making the diagnosis more challenging. The sensitivity of identifying pituitary adenomas decreased from 80 to 72% after excluding macroadenomas in a previous study [12], whereas the sensitivity of identifying pituitary microadenomas in our study was 90–93% on hrMRI. In the current study, hrMRI performed better than cMRI, dMRI, and combined cMRI and dMRI, with high AUC (0.95–0.97), high sensitivity (90–93%), and high specificity (100%), superior to previous studies [8, 11,12,13]. The high sensitivity of hrMRI for identifying pituitary adenomas will help surgeons improve the postoperative remission rate [4]. The high specificity of hrMRI will assist clinicians to consider ectopic ACTH syndrome, and then perform imaging to identify ectopic tumors. Besides, the inter-observer agreement for identifying pituitary microadenomas was almost perfect on hrMRI (κ = 0.91), which was moderate on cMRI (κ = 0.50) and dMRI (κ = 0.57). Therefore, hrMRI using the 3D FSE sequence is a potential alternative that can significantly improve the identification of pituitary microadenomas.

Limitations of the study included its retrospective nature and the relatively small sample size in patients with ectopic ACTH syndrome as negative controls. The bias may be introduced in the patient inclusion process. Only those patients who underwent all the cMRI, dMRI, and hrMRI scans were included. In fact, some patients will bypass hrMRI when obvious pituitary adenomas were detected on cMRI and dMRI. These patients were not included in the current study because of lack of hrMRI findings. Given the situation, the sensitivity of identifying pituitary adenomas will be higher with the enrollment of these patients. Besides, the timing of the sequence acquisition after contrast injection is essential [16] and bias may be introduced due to the postcontrast enhancement curve of both the pituitary gland and the microadenoma [14]. In the future, a prospective study with different sequence acquisition orders is needed to minimize possible interference caused by the postcontrast enhancement curve. Moreover, a larger sample size is also needed to verify the diagnostic performance of hrMRI using 3D FSE sequence for identifying pituitary microadenomas and to determine whether it can replace 2D FSE or 3D SPGR sequences for routinely evaluating the pituitary gland.

In conclusion, hrMRI with 3D FSE sequence showed higher diagnostic performance than cMRI and dMRI for identifying pituitary microadenomas in patients with Cushing’s syndrome.