Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of osilodrostat in patients with Ectopic Cushing syndrome (ECS).

Methods

A retrospective, multicenter, real-world study of patients with ECS treated with osilodrostat. The main efficacy endpoint was the proportion of patients who were complete responders (urinary free cortisol [UFC] < the upper limit of normal [ULN] or adrenal insufficiency development).

Results

A total of 17 patients with ECS were identified. Most of the cases (88.2%, n = 15) were classified as severe Cushing´s syndrome (UFC > 5 ULN). Two patients received osilodrostat as first-line therapy, 9 as second line and 6 as a third line. Fourteen patients were treated with osilodrostat in monotherapy and 3 in combination with other treatments. The initial doses of osilodrostat ranged between 4 and 30 mg/day and the maximum doses between 4 and 60 mg/day. Response to osilodrostat was evaluated in 16 patients because one patient died few days (< 30) after the initiation of the treatment. We found that 88% (n = 14/16) were complete responders while 2 patients had partial response (UFC reduction > 50% but with no normalization). The median time to achieve hypercortisolism control was 4.5 weeks (range 1–12), and 40% of the cases had normal UFC after 1 month of treatment. Six patients developed adverse events associated with the use of osilodrostat: 3 had adrenal insufficiency, 1 QT prolongation and 1 deterioration of blood pressure control.

Conclusion

Overall, osilodrostat controls hypercortisolism in approximately 90% of the patients with ECS and severe hypercortisolism and with normalization of UFC in 40% of cases after just 4 weeks of treatment. Therefore, osilodrostat should be considered as first-line treatment in patients with ECS, especially in patients with severe hypercortisolism.

Significance statement

Several phase II and III clinical trials have proved the efficacy of osilodrostat in patients with Cushing´s disease, reporting UFC normalization in 70 to 90% of the cases. However, few data exist about real-world efficacy of osilodrostat. In addition, to best of our knowledge, no previous study has evaluated the efficacy and safety of osilodrostat in patients with Ectopic Cushing´s syndrome (ECS) in the Spanish population. Thus, in this multicenter study we evaluated the efficacy and safety of osilodrostat for the treatment of hypercortisolism in patients with ECS in our country. We enrolled 17 patients with ECS and 88.2% had severe Cushing´s syndrome. We found that 88% were complete responders while 2 patients had partial response (UFC reduction > 50% but with no normalization).

Introduction

Endogenous Cushing´s syndrome (CS) is a rare chronic and systemic clinical condition caused by long-term and inappropriate exposure to glucocorticoids, and with an estimated incidence of 2 to 6 cases per million individuals per year [1]. There are three main causes of endogenous CS. The most frequent, about 65% are due to a pituitary corticotroph tumor, known as Cushing’s disease (CD). Adrenal CS represents approximately 30% of all CS, while the remaining 5% are due to non-pituitary tumors that secrete adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), referred to as ectopic Cushing’s syndrome (ECS) [2].

In relation to ECS, it is usually associated with intense and severe hypercortisolism, often leading to life- threatening clinical manifestations [3]. For this reason, in this situation a significant reduction of the cortisol production is urgently needed to improve all these comorbidities and prevent further life-threatening complications [4]. The first-line treatment for rapidly reducing cortisol levels includes adrenal steroidogenesis inhibitors such as etomidate, osilodrostat, metyrapone, and ketoconazole, either alone or in combination [5, 6]. Among them, etomidate and osilodrostat are the most effective and with rapid onset of action [6, 7]. However, etomidate is only available for intravenous administration; thus, it is usually reserved for patients with CS who require urgent control of hypercortisolism and in whom oral administration is not feasible [8].

Osilodrostat is an imidazole derivate that inhibits 11β-hydroxylase (CYP11B1) and aldosterone synthase (CYP11B2) and it is orally administered and rapidly and significantly reduces urinary free cortisol (UFC) levels [9]. Although primarily studied in CD, its efficacy has also been observed in rarer forms of CS, including adrenocortical carcinoma (ACC) and ECS [8, 10, 11]. In this regard, several phase II and III clinical trials, the LINC trials, have proved its efficacy, reporting UFC normalization in 70 to 90% of the cases of CD in parallel with significant improvement in body weight, blood pressure (BP), glucose metabolism, lipid profile, psychological status and quality of life [12,13,14,15]. However, few data exist about real-world efficacy of osilodrostat [6, 16, 17]. In addition, to best of our knowledge, no previous study has evaluated the efficacy and safety of osilodrostat in patients with ECS in the Spanish population. Thus, we aimed to evaluate the efficacy and safety of osilodrostat, both in monotherapy and in combination with other treatments, for the treatment of hypercortisolism in patients with ECS in our country.

Methods

Study design and definitions

A multicenter national retrospective study of patients with ECS diagnosis was performed. The diagnosis of CS was based on current clinical practice guidelines and recommendations [18]. The inclusion criteria to enter in the study were: (i) to have a biochemically confirmed diagnosis of CS of ectopic origin (ii) patient has been treated with osilodrostat at any time during the medical treatment of hypercortisolism and (iii) available complete hormonal and clinical information before and after treatment with osilodrostat. The diagnosis of ECS was made when at least one of the following criteria were met: (i) bilateral inferior petrosal sinus sampling (BIPSS) with a basal petrosal sinus to peripheral ACTH ratio lower than 2:1 or lower than 3:1 after stimulation from either petrosal sinus (n = 5), (ii) positive ACTH immunostaining in the ectopic tumor and/or the development of adrenal insufficiency following resection of the primary tumor (n = 6) or (iii) severe hypercortisolism in a patient with a known primary neuroendocrine tumor and no evidence of a pituitary microadenoma on MRI study (n = 9). The patients were followed by different endocrinologists in expert endocrinology departments at the participating hospitals.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal. Madrid. Spain (approval date: 26 November 2024, code: ACTA 472) and in each collaborating center. The consent exemption was approved by the Ethical Committee due to the retrospective nature of the study. Informed consent was requested only for patients who continued follow-up.

Outcomes and variables

The main efficacy endpoint was the proportion of patients who were complete responders (mean UFC < ULN or adrenal insufficiency (AI) development). In addition, we evaluated the proportion of partial responders (mean UFC > ULN and with > 50% reduction from baseline levels) and non-responders (mean UFC > ULN and with < 50% reduction from baseline). This information was evaluated after 2 weeks of treatment, after 1 and 3 months and at the last available follow-up visit. However, due to the retrospective nature information of UFC was not available in all patients at these different time points. In addition, we have evaluated the time necessary to achieve hypercortisolism control.

UFC and late-night salivary cortisol (LNSC) were measured using standard CLIA, ELISA and radioimmunoassay and the normal range was different across center. Thus, we estimated the deviations above the ULN for each UFC and LNSC values.

As secondary outcomes, we evaluated the evolution of BP, serum potassium levels, body weight (kg), glucose levels, HbA1c and lipid profile after treatment. This information was registered before osilodrostat treatment and after 1 and 3 months and at the last available follow-up visit.

Escape from response was defined as mean UFC > ULN on at least one consecutive visit at the highest tolerated osilodrostat dose after previously attaining UFC normalization. Safety and tolerability of osilodrostat treatment were assessed at month 1, 3 and at the last follow-up visit.

The individual duration and doses of prior treatments by metyrapone, ketoconazole and other treatments were also described. In relation to osilodrostat treatment, we collected information on starting, maximum and maintenance doses. Information about the treatment strategy used was registered: titration (when osilodrostat was used without combination with hydrocortisone or another glucocorticoid replacement therapy), block and replace (B&R) regimen upfront or initial titration followed by B&R.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed with STATA 15. Categorical variables were expressed as percentages and (absolute values of variable) and quantitative variables as mean and standard deviation or median ± range depending on if the assumption of normality was met. The paired T test was used for comparison of UFC, serum cortisol, clinical score, systolic BP (SBP), diastolic BP (DBP), body mass index (BMI), and the biological parameters kalemia, glycemia, and HbA1c before and during osilodrostat therapy. In all cases, a two-tailed P value < 0.05 was considered as statistically significant.

Results

Baseline characteristics and previous treatments

A total of 17 patients with ECS were included (6 of lung origin [1 bronchial neuroendocrine tumor (NET), 2 large cells carcinoma and 2 microcytic carcinomas], 3 pancreatic NETs, 2 thymic NETs, 1 medullary thyroid cancer, 1 parotid NET, 1 olfactory neuroblastoma and 3 occult tumors). The baseline characteristics of the patients at the time of the ECS diagnosis are described in Table 1. The median age was 57.6 years (range 27 to 64) and 10 were females and 7 males. We found that UFC levels before osilodrostat treatment were significantly lower in those cases who underwent previous primary tumor resection (8.3 ± 5.87 vs. 23.2 ± 17.75 x ULN, P = 0.027).

In relation to the treatment of the extra-pituitary tumor, the patient with olfactory neuroblastoma underwent pituitary surgery before the diagnosis of ECS since he had been incorrectly classified as CD. No patient underwent bilateral adrenalectomy. Five patients were submitted to resection of the primary tumor (2 achieved cure of the hypercortisolism after surgery [1 pancreatic NET and 1 thymic NET], but they recurred during follow-up). Other therapies included first generation somatostatin receptor ligands in 7 patients, chemotherapy in 7, immunotherapy in 2, local treatment in 5 and lutecium in 4 cases (Table 2). In relation to the duration and doses of prior treatments by metyrapone, ketoconazole and other treatments are described in Table 2. The first line therapy was ketoconazole in 10 patients, metyrapone in 4, osilodrostat in 2 and ketoconazole in association with metyrapone in one case. In relation to second-line, osilodrostat was the election in 9 cases while 5 were treated with metyrapone and 1 with ketoconazole (the two patients treated with osilodrostat as first-line therapy were controlled with this treatment). Among the 10 patients treated with ketoconazole at any point, only 3 (30%) were complete responders. Among those treated with metyrapone (n = 6), 2 (33%) achieved complete response, as did 1 of the 2 patients (50%) treated with the combination of ketoconazole and metyrapone (Table 3).

Efficacy and safety of osilodrostat

Two patients received osilodrostat as first line therapy, 9 as second line and 6 as a third line. Fourteen patients were treated with osilodrostat in monotherapy and 3 in combination with other treatments (osilodrostat + ketconozole in 2 and osilodrostat + metyrapone in 1). There were 6 patients treated with titration, 7 treated with titration following by B&R and 4 with B&R (in all cases hydrocortisone was the glucocorticoid used) from the beginning of the therapy (Table 4). Median disease duration before osilodrostat prescription was 10.7 months (range 1–70 months).

The initial doses of osilodrostat ranged between 4 and 30 mg/day and the maximum doses between 4 and 60 mg/day (Table 4). The median doses at last visit (maintenance doses) were 9 mg/day (range 2–60). There was a tendency to a negative correlation between the initial doses employed and the time to achieve UFC normalization (r = 0.43, P = 0.096). The median duration of the treatment with osilodrostat at the time of the analysis was 3.5 months (range 1–31).

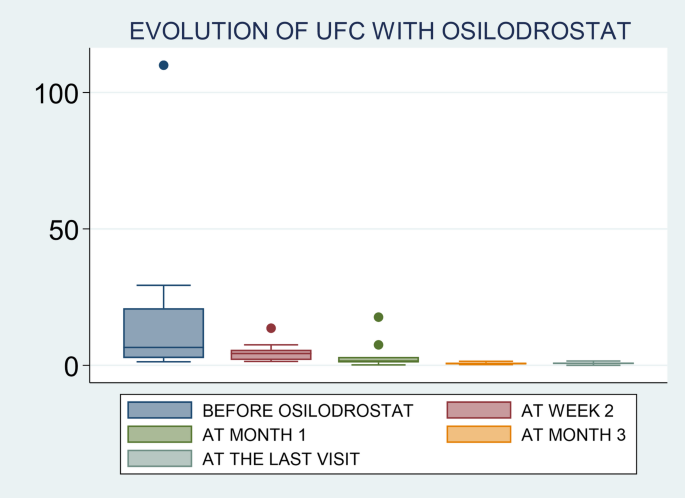

Response to osilodrostat was evaluated only in 16 out of the 17 patients because 1 patient died few days after the initiation of the treatment, with no possibility of reassessed UFC levels. The median time to achieve hypercortisolism control in these patients was 4.5 weeks (range 1 to 12), and 40% of cases had normal UFC after 1 month of treatment. We found that 88% (n = 14/16) were complete responders while 2 patients had partial responses. No cases of escape to hypercortisolism control were reported. Three of the 14 patients classified as responders had not available UFC levels after therapy, but they developed adrenal insufficiency; thus, they were classified as responders. The two patients with partial response, one was treated for less than 1 month and died due to tumor progression and the other one experienced a decrease in UFC from 29 times the ULN to 1.6 the ULN after 4.5 months of treatment, but no normalization (Table 4and Fig. 1). Therefore, we can say that the first patient is not a real partial responder considering that he was treated with low doses of osilodrostat (4 mg/day) and for less than one month, with no possibility of doses titration.

When we evaluated UFC levels in the different timepoints, we found that the rate of UFC normalization was 0% (n = 0/9) at week 2, 36% (n = 4/11) at month 1, 90% (n = 9/10) at month 3 and 83.3% (n = 10/12) at the last follow-up visit.

No significant differences were detected in the degree of UFC reduction between patients with a previous primary tumor resection and those with no previous surgery (−5.4 ± 5.48 vs. −20.19 ± 34.76 x ULN, P = 0.245). Neither when comparing patients with and without metastasis (−16.6 ± 31.82 vs. −10.1 ± 12.99 x ULN, P = 0.648) nor in patients starting osilodrostat within 6 months of the CS diagnosis and those who started treated after 6 months (−26.8 ± 41.67 vs. −6.0 ± 6.89 x ULN, P = 0.279).

Six patients developed adverse events (AEs) associated with the use of osilodrostat: 3 patients had AI, 1 QT prolongation and 1 patient deterioration of BP control (Table 4). Six patients died few months after osilodrostat initiation due to tumoral progression or complications. No patients discontinued osilodrostat due to the development of AEs. No alteration in liver function abnormalities leading to drug discontinuation or reduction were reported for any patients receiving osilodrostat as monotherapy, either as first-line or second-line therapy.

No differences were detected in UFC levels at diagnosis of ECS (7.9 ± 2.73 vs. 20.0 ± 17.0 x ULN, P = 0.345) and before starting osilodrostat (3.0 ± 2.28 vs. 18.5 ± 28.15 x ULN, P = 0.462) nor in the duration of hypercortisolism (1.3 ± 2.01 vs. 1.9 ± 2.09 years, P = 0.621) or in the time to normalize UFC with osilodrostat (6.3 ± 4.7 vs. 4.2 ± 3.2 weeks, P = 0.350) between patients who developed adrenal insufficiency and those who did not develop it.

Impact of osilodrostat on comorbidities

At the time of the ECS diagnosis, hypertension was present in 82.4% (n = 14), diabetes in 58.8% (n = 10) and hypokalemia in 76.5% (n = 13). The median serum potassium levels were 3.1 mEq/mL (range 1.5 to 5.1). Most of the cases (88.2%, n = 15) were classified as severe CS (Table 1).

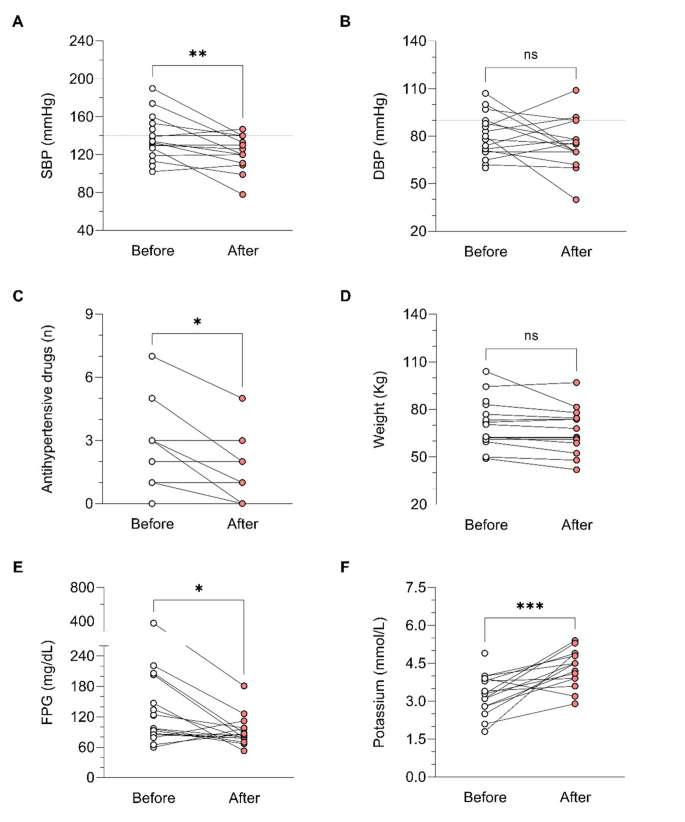

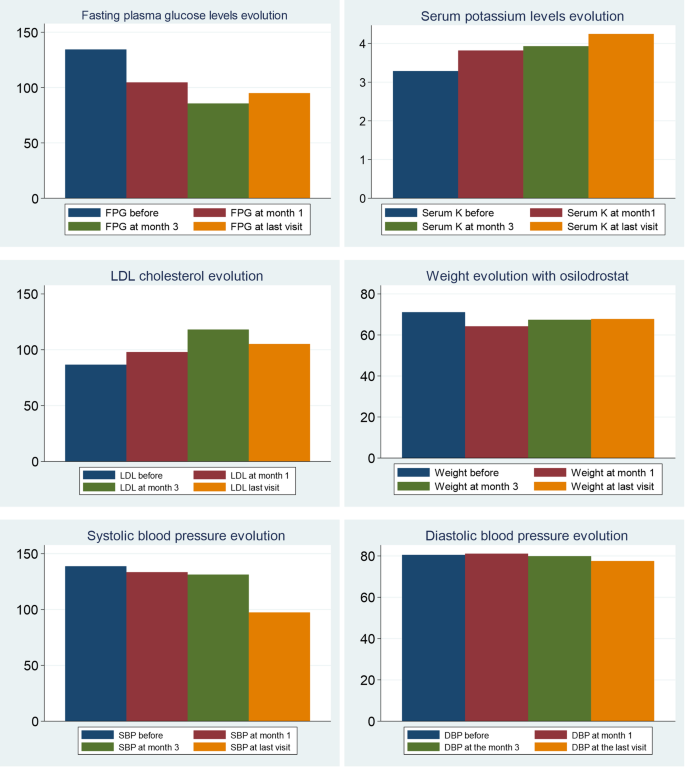

In relation to BP control during osilodrostat therapy, there was a significant decrease in SBP in parallel with a decrease in the number of antihypertensive medications, but no significant differences in DBP (Table 5). The weight tended to decrease after osilodrostat therapy, but statistically significance was not reached. There was a significant improvement in glycemic control, with a reduction in the fasting plasma glucose (FPG) levels and HbA1c. Serum potassium experienced a significant increase after therapy. In this regard, hypokalemia was corrected in 10 of the 13 patients (77%) who presented hypokalemia at diagnosis (Table 5and Fig. 2). Hypokalemia correction was evident after only 1 month of treatment in 7 out of these 10 patients (70%) while in the other 3 cases occurred later. Figure 3 represents the FPG, serum potassium and cholesterol levels before starting osilodrostat, after 1 and 3 months and in the last visit.

Discussion

This is the first study with real world data focused on evaluating the efficacy and safety of osilodrostat in patients with ECS in Spain. In addition, it represents the second largest series of patients with ECS treated with osilodrostat after the Dormoy study [6]. The main results of our study reveal that: (i) osilodrostat therapy is usually initiated as second or even third line therapy in patients with ECS, despite the fact that most of these patients present with severe hypercortisolism; (ii) its efficacy is high, leading to UFC normalization in approximately 90% of the cases and (iii) overall, it is a well-tolerated drug although AI is a relatively frequent AE.

In relation to the etiologies of ECS in our series, we found that aggressive lung carcinomas and pancreatic NET were the most frequent ACTH/CRH-secreting tumors. This distribution is quite different than the global epidemiology reported in other series where bronchial carcinoids are the most frequent cause [19]. The higher prevalence of aggressive tumors in our series is probable explained by a selection bias since in general patients who received osilodrostat had a more severe CS, and it is known that in general metastatic and malignant tumors are associated with higher UFC and a more severe CS phenotype [20].

Osilodrostat is an oral imididazole derivate that inhibits 11β-hydroxylase, the enzyme that catalyzes the final step of cortisol synthesis in the adrenal cortex [9]. It has been approved by the FDA and the EMA in 2020 for CD (CS in Europe) treatment in adults not cured by pituitary surgery or in whom pituitary surgery is not appropriate. There are several clinical trials in patients with CD that have demonstrated a rapid and sustained reduction in cortisol levels and a significant improvement of the cardiometabolic profile and quality of life in these patients [13,14,15, 21]. Nevertheless, only few data exist on the efficacy of this therapy in real-world setting. One of the largest studies was conducted by Dormoy A et al. [6] and included 33 patients with severe CS due to an ECS. In this study, osilodrostat led to control of hypercortisolism in 82% of cases when used as first-line monotherapy, 100% when used as second-line monotherapy, and in 68% in the group receiving combination therapy. Another very recent real-world study (ILLUSTRATE) focused on evaluating the efficacy of osilodrostat use in patients with various etiologies of CS in the United States, with 42 patients included of whom three had ECS, described normalization of UFC in 70% of the cases [22]. Thus, our results (88% of complete UFC normalization) are in line with the reported in previous series, and in fact, they are even slightly better than the described by other authors [22]. In this regard, it is important to highlight that although we were not able to identify predictors of response (probably due to the low number of non-complete responders patients, only 2 cases), we observed that the initial employed doses of osilodrostat were associated with the time to achieve normalization of UFC. It means, as higher initial doses of osilodrostat, shorter time to normalize UFC would be needed. In this regard, it is important to individualize the management of patients with CS, not only in the selection of the most appropriate drug, but also in the doses of the treatment and approach (titration or B&R). For example, if a patient was previously treated with high doses of other steroidogenesis inhibitors or has intense hypercortisolism, we should start osilodrostat at doses of at least 4–10 mg/day, or even higher. For example, in our study the most commonly used initial dose was 4 mg/day (in 12 out of the 17 patients; 70%), but 9 out of these 12 patients (65%) had to increase the dose to achieve proper hypercortisolism control. In fact, we observed that the final dose that controlled hypercortisolism was 4 mg/day only in 3 patients. Thus, we should consider higher starting doses in these patients with ECS and severe hypercortisolism. In the ILLUSTRATE study, the proportion of patients treated with 2 mg twice daily was 64.3% [22], however, most of the cases (34 out of 42) in these study had CD with a less severe hypercortisolism. Nonetheless, it is possible that if higher doses were employed from the beginning the proportion of response would have been higher, or at least a faster control of hypercortisolism would have been reached as stipulated in the algorithm proposed by Dormoy et al. [6]. Nonetheless, we found that there is wide heterogeneity of the initiation doses and the time to UFC normalization across the patients. For example, the two patients with the shortest time of normalization (patients 10 & 12) had relatively low doses compared to some other patients (notably patient 2 who did not reach complete response, and patient 4 who normalized UFC after 2 weeks). In this regard, in general it seems that the response to osilodrostat is quite unpredictable.

It is important to highlight that patients with ECS had a higher mortality when compared with CS of other etiologies [23]. For example, in our study 35% of the patients died after a short follow-up period and 88% of the patients had severe hypercortisolism. Severe hypercortisolism is a life-threatening medical condition requiring immediate systemic assessment and urgent therapy [24]. For this reason, the control of hypercortisolism should be prioritized over etiological investigation. For this purpose, the first-line treatment for rapidly reducing cortisol levels includes adrenal steroidogenesis inhibitors such as etomidate and osilodrostat that have a rapid onset of action [5, 6]. Despite these recommendations and the high UFC levels in our cohort, we can see that due to the current prescription conditions in Spain, most of the patients were treated with osilodrostat as second or even third line-therapy. In fact, only two of the 17 patients received osilodrostat as first line therapy and the time from the diagnosis of ECS for the initiation of osilodrostat was longer than 5 months in ten out of the 17 patients. In this regard we have to take into account that in these patients the time to achieve control of hypercortisolism is especially important because the risk of severe complications such as thromboembolism or intercurrent infections is very high [25]. Supporting the use of osilodrostat in this scenario, a recent Phase II study in Japan reported that osilodrostat effectively reduced UFC levels in all nine patients with severe endogenous CS, with over 80% reduction in 6 out of 7 patients by week 12 [26]. Another very potent steroidogenesis inhibitor, with a very rapid onset of action is etomidate, but this treatment should be administered intravenously; thus, it is usually reserved for patients with severe CS who require urgent control of hypercortisolism and in whom oral administration is not feasible (e.g., severe psychosis, sepsis, or ileus) [8].

Osilodrostat was overall well tolerated in our study population, with a low incidence of AEs. The most notable AE observed was AI, reported in 17.6% of the treated patients. This rate is considerably lower than that reported in the LINC 3 clinical trial, where approximately 54% of participants experienced AEs related to hypocortisolism, including both cortisol withdrawal syndrome (CWS) and AI.

However, it is important to recognize the challenges associated with evaluating CWS, particularly in patients undergoing active oncological treatment. These overlapping clinical presentations may have contributed to an underestimation of CWS in our cohort. Only one patient was explicitly reported to have experienced CWS, resulting in a total hypocortisolism-related AE incidence of 23.5%. The escalation of osilodrostat dosing was highly variable among patients, and no consistent correlation was identified between dosage levels and the risk of AEs.

Given this potential hypocortisolism due to its high efficacy and quick onset of action, initiation of education and counseling of patients receiving osilodrostat is essential is recommended to be performed at treatment initiation. Patients should be trained to recognize early signs and symptoms of hypocortisolism to ensure timely intervention. Some centers are recommending stress dose of corticoids at treatment initiation. Anyway, nonspecific direct cortisol immunoassays may overestimate cortisol levels, potentially masking the diagnosis of adrenal insufficiency in patients with CS receiving an 11β-hydroxylase inhibitor [9]. In this context, the B&R regimen appears to be a particularly safe and effective therapeutic approach, especially considering the dynamic and often unpredictable fluctuations in cortisol secretion by ectopic tumors and the presumed positive effect of the oncologic antitumoral treatment. What is more, given its high potency, osilodrostat can be used as monotherapy without needing combination with other agents. This reduces the potential for increased side effects and minimizes polypharmacy compared to other oral inhibitors of steroidogenesis.

Nevertheless, case reports of prolonged adrenal AI has been reported following discontinuation of osilodrostat, reinforcing the need for sustained, close monitoring on long term after therapy cessation [27,28,29].

During osilodrostat therapy, gradual improvements in cardiovascular, metabolic parameters including blood pressure, glycemia, weight and normalization of potassium levels. As in Spain osilodrostat have been majorly prescribed in the second line previous treatment of severe hypokaliemia by potassium supplementation and treatment with mineralocorticoid antagonists (MRA) have been already initiated and sever hypopotassemia remitted. Anyway, during osilodrostat treatment as described by other authors potassium improved rapidly permitting the reduction of potassium and MRA therapy. These effects reflect also the dual inhibitory action of osilodrostat on both CYP11B1 and even in a lower degree also on CYP11B2 enzymes. Except for a single case of QT interval prolongation, no major cardiovascular events, electrolyte imbalances or liver function or increase in lipids were reported in our patient group, which aligns with the safety profiles of all other adrenal steroidogenesis inhibitors.

We are aware that our study has some limitations. One of them is the reduced number of patients included. Nevertheless, this is still the second largest series of cases reported in the literature. One of the main limitations is the retrospective nature of the study, and the variability of the protocols used in every participant centers, including different starting doses, no available information on UFC and on cardiometabolic parameters in all the evaluation times. In addition, we are aware that the classification of CS as severe based only on UFC has some limitations as the association with severe complications should also be considered. In this regard, a patient may have a severe CS due to the development of these complications (severe hypokalemia and complications such as uncontrolled hypertension, sepsis, heart failure or acute psychosis, among others) and maintain UFC < 5 the ULN [30]. Moreover, it is not uncommon that patients with severe CS have deteriorated kidney function that may also underestimate UFC levels [31]. Nonetheless, despite these limitations, the results provide invaluable information on the real-world use of osilodrostate in patients with ECS Spain, supporting the results of the clinical trials.

Conclusion

Overall, osilodrostat controls hypercortisolism in approximately 90% of the patients with ECS and severe hypercortisolism and in 50% of cases UFC is normal at only 4 weeks of treatment. Thus, considering its efficacy and the severity of ECS that is a life-threating complication, osilodrostat should be considered as a first line therapy in these patients in order to reduce the risk of hypercortisolism complications and mortality.

References

-

Hakami OA, Ahmed S, Karavitaki N (2021) Epidemiology and mortality of Cushing’s syndrome. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BEEM.2021.101521

-

Valassi E (2022) Clinical presentation and etiology of Cushing’s syndrome: data from ERCUSYN. J Neuroendocrinol. https://doi.org/10.1111/JNE.13114

-

Ragnarsson O, Juhlin CC, Torpy DJ, Falhammar H (2024) A clinical perspective on ectopic cushing’s syndrome. Trends Endocrinol Metab 35:347–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.TEM.2023.12.003

-

van Haalen FM, Kaya M, Pelsma ICM, Dekkers OM, Biermasz NR, Cannegieter SC et al (2022) Current clinical practice for thromboprophylaxis management in patients with Cushing’s syndrome across reference centers of the European Reference Network on Rare Endocrine Conditions (Endo-ERN). Orphanet J Rare Dis. https://doi.org/10.1186/S13023-022-02320-X

-

Muthukuda DT, Liyanaarachchi KD, Jayawickreme KP, Mahesh PKB, Ruwanga VGD, Kumar S et al (2025) Etomidate in Severe Cushing Syndrome: a systematic review. J Endocr Soc. https://doi.org/10.1210/jendso/bvaf039

-

Dormoy A, Haissaguerre M, Vitellius G, Cao C, Do, Geslot A, Drui D et al (2023) Efficacy and safety of Osilodrostat in paraneoplastic Cushing syndrome: A Real-World multicenter study in France. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 108:1475–1487. https://doi.org/10.1210/CLINEM/DGAC691

-

Dzialach L, Sobolewska J, Respondek W, Wojciechowska-Luzniak A, Kuca P, Witek P (2025) Is there still a place for etomidate in the management of Cushing’s syndrome? The experience of a single center of low-dose etomidate and combined etomidate-osilodrostat treatment in severe hypercortisolemia. Endocrine. https://doi.org/10.1007/S12020-024-04135-1

-

Marques JVO, Boguszewski CL (2021) Medical therapy in severe hypercortisolism. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.BEEM.2021.101487

-

Creemers SG, Feelders RA, De Jong FH, Franssen GJH, De Rijke YB, Van Koetsveld PM et al (2019) Osilodrostat is a potential novel steroidogenesis inhibitor for the treatment of Cushing syndrome: an in vitro study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 104:3437–49. https://doi.org/10.1210/JC.2019-00217

-

Haissaguerre M, Puerto M, Nunes ML, Tabarin A (2020) Efficacy and tolerance of Osilodrostat in patients with severe cushing’s syndrome due to non-pituitary cancers. Eur J Endocrinol 183:L7–L6. https://doi.org/10.1530/EJE-20-0557

-

Bessiène L, Bonnet F, Tenenbaum F, Jozwiak M, Corchia A, Bertherat J et al (2021) Rapid control of severe ectopic Cushing’s syndrome by oral osilodrostat monotherapy. Eur J Endocrinol 184(5):L13. https://doi.org/10.1530/EJE-21-0147

-

Fleseriu M, Pivonello R, Young J, Hamrahian AH, Molitch ME, Shimizu C et al (2016) Osilodrostat, a potent oral 11β-hydroxylase inhibitor: 22-week, prospective, phase II study in cushing’s disease. Pituitary 19:138–148. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11102-015-0692-Z

-

Pivonello R, Fleseriu M, Newell-Price J, Bertagna X, Findling J, Shimatsu A et al (2020) Efficacy and safety of osilodrostat in patients with Cushing’s disease (LINC 3): a multicentre phase III study with a double-blind, randomised withdrawal phase. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology 8:748–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(20)30240-0

-

Gadelha M, Bex M, Feelders RA, Heaney AP, Auchus RJ, Gilis-Januszewska A et al (2022) Randomized trial of Osilodrostat for the treatment of Cushing disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 107:E2882–E2895. https://doi.org/10.1210/CLINEM/DGAC178

-

Fleseriu M, Newell-Price J, Pivonello R, Shimatsu A, Auchus RJ, Scaroni C et al (2022) Long-term outcomes of osilodrostat in Cushing’s disease: LINC 3 study extension. Eur J Endocrinol 187:531–41. https://doi.org/10.1530/EJE-22-0317

-

Tabarin A, Haissaguerre M, Lassole H, Jannin A, Paepegaey AC, Chabre O et al (2022) Efficacy and tolerance of osilodrostat in patients with Cushing’s syndrome due to adrenocortical carcinomas. Eur J Endocrinol. https://doi.org/10.1530/EJE-21-1008

-

Detomas M, Altieri B, Deutschbein T, Fassnacht M, Dischinger U (2022) Metyrapone versus osilodrostat in the short-term therapy of endogenous Cushing’s syndrome: results from a single center cohort study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 13:903545. https://doi.org/10.3389/FENDO.2022.903545

-

Motohashi K, Osawa N, Yamaji T, Tanioka T, Ibayashi H (2025) Cushing syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Prim 11:3141–50. https://doi.org/10.1038/S41572-024-00588-W

-

Ferone D, Albertelli M (2014) Ectopic Cushing and other paraneoplastic syndromes in thoracic neuroendocrine tumors. Thorac Surg Clin 24:277–283. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.thorsurg.2014.05.002

-

Araujo Castro M, Marazuela Azpiroz M (2018) Two types of ectopic Cushing syndrome or a continuum? Rev Pituit 21:535–544. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11102-018-0894-2

-

Pivonello R, Fleseriu M, Newell-Price J, Shimatsu A, Feelders RA, Kadioglu P et al (2024) Improvement in clinical features of hypercortisolism during osilodrostat treatment: findings from the Phase III LINC 3 trial in Cushing’s disease. J Endocrinol Invest 47:2437–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/S40618-024-02359-6

-

Fleseriu M, Auchus RJ, Huang W, Spencer-Segal JL, Yuen KCJ, Dacus KC et al (2025) Osilodrostat Treatment of Cushing Syndrome in Real-World Clinical Practice: findings from the ILLUSTRATE study. J Endocr Soc. https://doi.org/10.1210/JENDSO/BVAF046

-

Pivonello R, Isidori AM, De Martino MC, Newell-Price J, Biller BMK, Colao A (2016) Complications of Cushing’s syndrome: state of the art. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 4:611–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-8587(16)00086-3

-

Alexandraki KI, Grossman AB (2016) Current strategies for the treatment of severe Cushing’s syndrome. Expert Rev Endocrinol Metab 11:65–79. https://doi.org/10.1586/17446651.2016.1123615

-

Stuijver DJF, Van Zaane B, Feelders RA, Debeij J, Cannegieter SC, Hermus AR et al (2011) Incidence of venous thromboembolism in patients with Cushing’s syndrome: a multicenter cohort study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 96:3525–32. https://doi.org/10.1210/JC.2011-1661

-

Tanaka T, Satoh F, Ujihara M, Midorikawa S, Kaneko T, Takeda T et al (2020) A multicenter, phase 2 study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of osilodrostat, a new 11β-hydroxylase inhibitor, in Japanese patients with endogenous cushing’s syndrome other than cushing’s disease. Endocr J 67:841–852. https://doi.org/10.1507/ENDOCRJ.EJ19-0617

-

Castinetti F, Amodru V, Brue T (2023) Osilodrostat in cushing’s disease: the risk of delayed adrenal insufficiency should be carefully monitored. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 98:629–630. https://doi.org/10.1111/CEN.14551

-

Ferriere A, Salenave S, Puerto M, Young J, Tabarin A (2024) Prolonged adrenal insufficiency following discontinuation of Osilodrostat treatment for intense hypercortisolism. Eur J Endocrinol 190(1):L1–L3

-

Poirier J, Bonnet-Serrano F, Thomeret L, Bouys L, Bertherat J (2023) Prolonged adrenocortical blockade following discontinuation of Osilodrostat. Eur J Endocrinol 188:K29–32

-

Araujo-Castro M, García-Centeno R, Aller J, Marazuela M, Soto A, Gálvez MÁ et al Executive summary of the consensus document for the management of severe cushing’s syndrome: consensus document of the neuroendocrinology focus group of the Spanish society of endocrinology and nutrition (SEEN). Endocrinol Diabetes Y Nutr 2025:501654. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ENDINU.2025.501654

-

Nieman LK, Castinetti F, Newell-Price J, Valassi E, Drouin J, Takahashi Y et al (2025) Cushing syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primers. https://doi.org/10.1038/S41572-024-00588-W

Funding

No funding support has been received for the publication of this study.

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

M.A.C. and FAH received speakers’ honoraria, consulting fees and research grants from Esteve and Recordati. P.I. received consulting fees from Recordati. M.D.O.G. and B.B. received speakers’ honoraria, consulting fees and research grants from Recordati. A.I.G. received speakers’ honoraria, consulting fees. The other authors declare no conflict of interest. There was not involved of the industry in any part of the study, including the design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation of the results.

Institutional Review Board statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal. Madrid. Spain (approval date: 26 November 2024, code: ACTA 472) and in each collaborating center.

Informed consent statement

Patient consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study. Informed consent was requested only for patients who continued follow-up or who were prospectively included.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Cite this article

Araujo-Castro, M., Garcia-Centeno, R., González Fernández, L. et al. Efficacy and safety of osilodrostat in patients with ectopic Cushing´s syndrome. a real-world study in Spain. J Endocrinol Invest (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40618-025-02769-0

- Received

- Accepted

- Published

- Version of record

- DOI https://doi.org/10.1007/s40618-025-02769-0

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s40618-025-02769-0

Filed under: Cushing's, Rare Diseases, Treatments | Tagged: ectopic, hypercortisolism, Osilodrostat, UFC | Leave a comment »