A young healthcare worker who contracted COVID-19 shortly after being diagnosed with Cushing’s disease was detailed in a case report from Japan.

While the woman was successfully treated for both conditions, Cushing’s may worsen a COVID-19 infection. Prompt treatment and multidisciplinary care is required for Cushing’s patients who get COVID-19, its researchers said.

The report, “Successful management of a patient with active Cushing’s disease complicated with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia,” was published in Endocrine Journal.

Cushing’s disease is caused by a tumor on the pituitary gland, which results in abnormally high levels of the stress hormone cortisol (hypercortisolism). Since COVID-19 is still a fairly new disease, and Cushing’s is rare, there is scant data on how COVID-19 tends to affect Cushing’s patients.

In the report, researchers described the case of a 27-year-old Japanese female healthcare worker with active Cushing’s disease who contracted COVID-19.

The patient had a six-year-long history of amenorrhea (missed periods) and dyslipidemia (abnormal fat levels in the body). She had also experienced weight gain, a rounding face, and acne.

After transferring to a new workplace, the woman visited a new gynecologist, who checked her hormonal status. Abnormal findings prompted a visit to the endocrinology department.

Clinical examination revealed features indicative of Cushing’s syndrome, such as a round face with acne, central obesity, and buffalo hump. Laboratory testing confirmed hypercortisolism, and MRI revealed a tumor in the patient’s pituitary gland.

She was scheduled for surgery to remove the tumor, and treated with metyrapone, a medication that can decrease cortisol production in the body. Shortly thereafter, she had close contact with a patient she was helping to care for, who was infected with COVID-19 but not yet diagnosed.

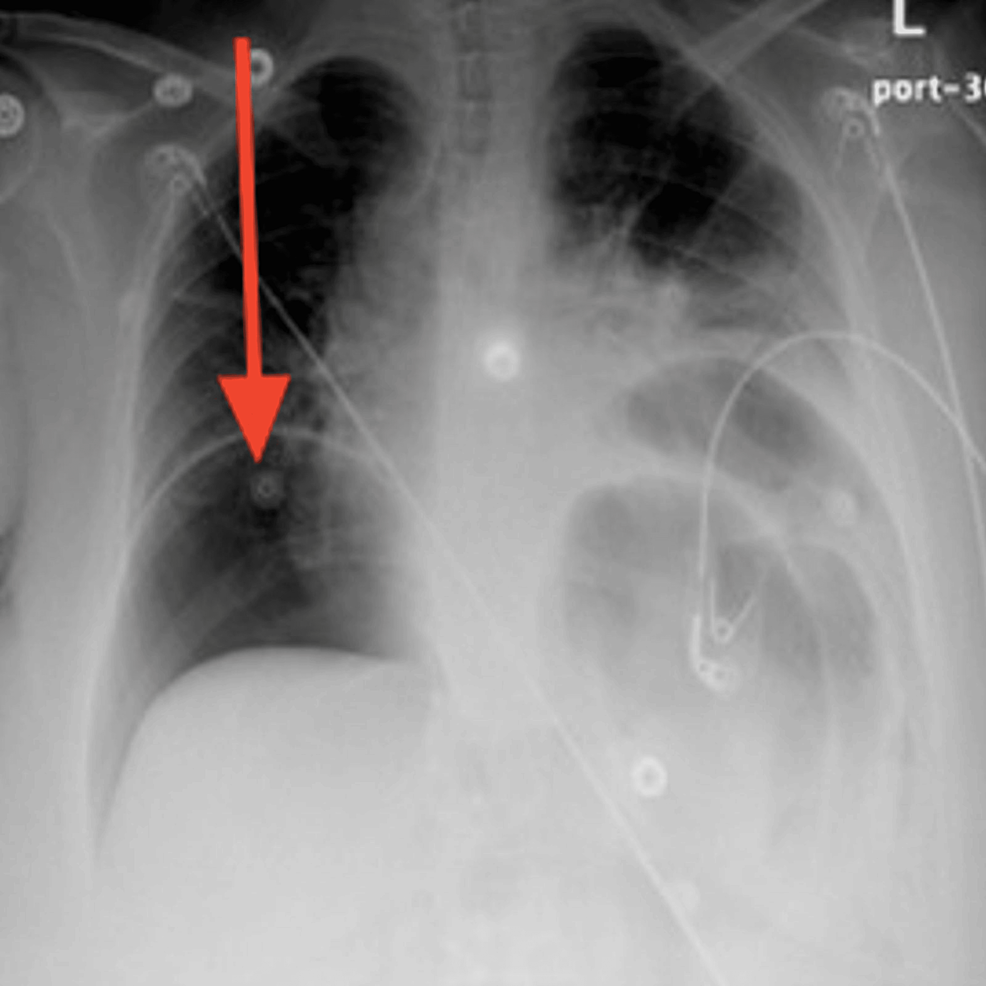

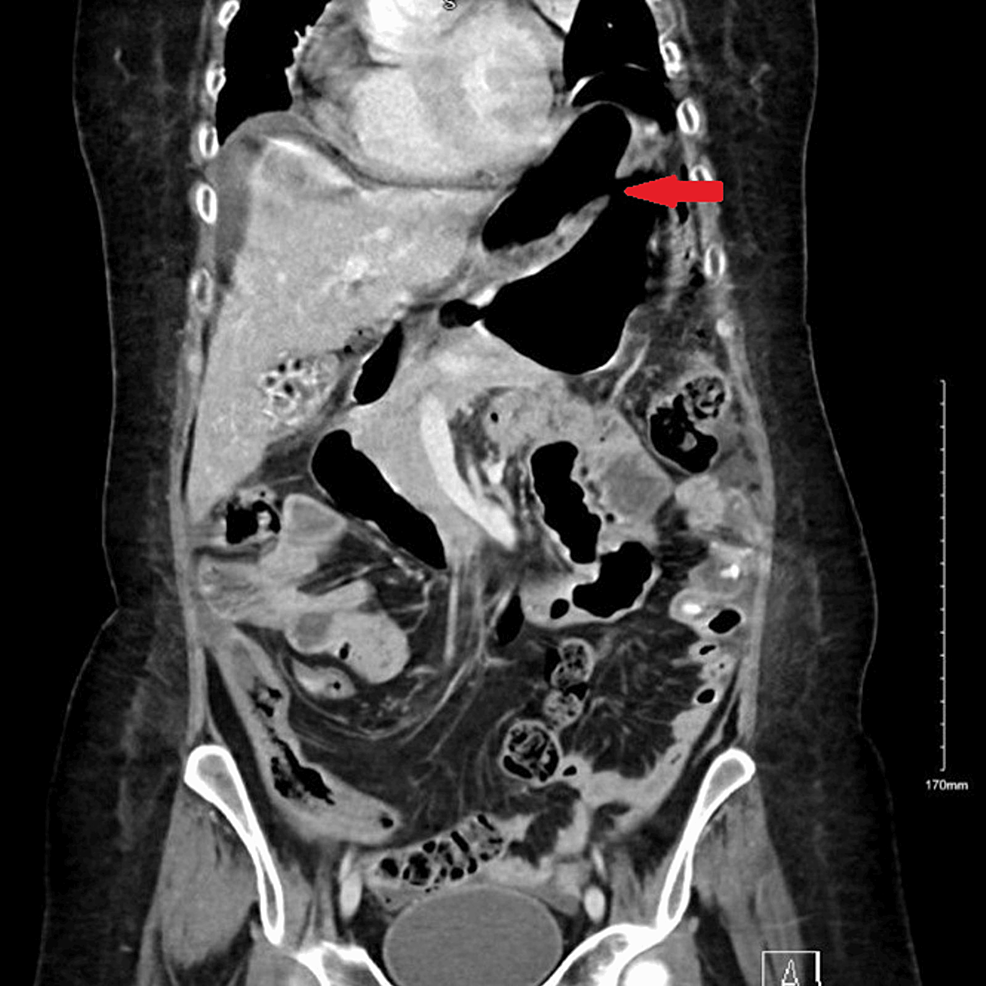

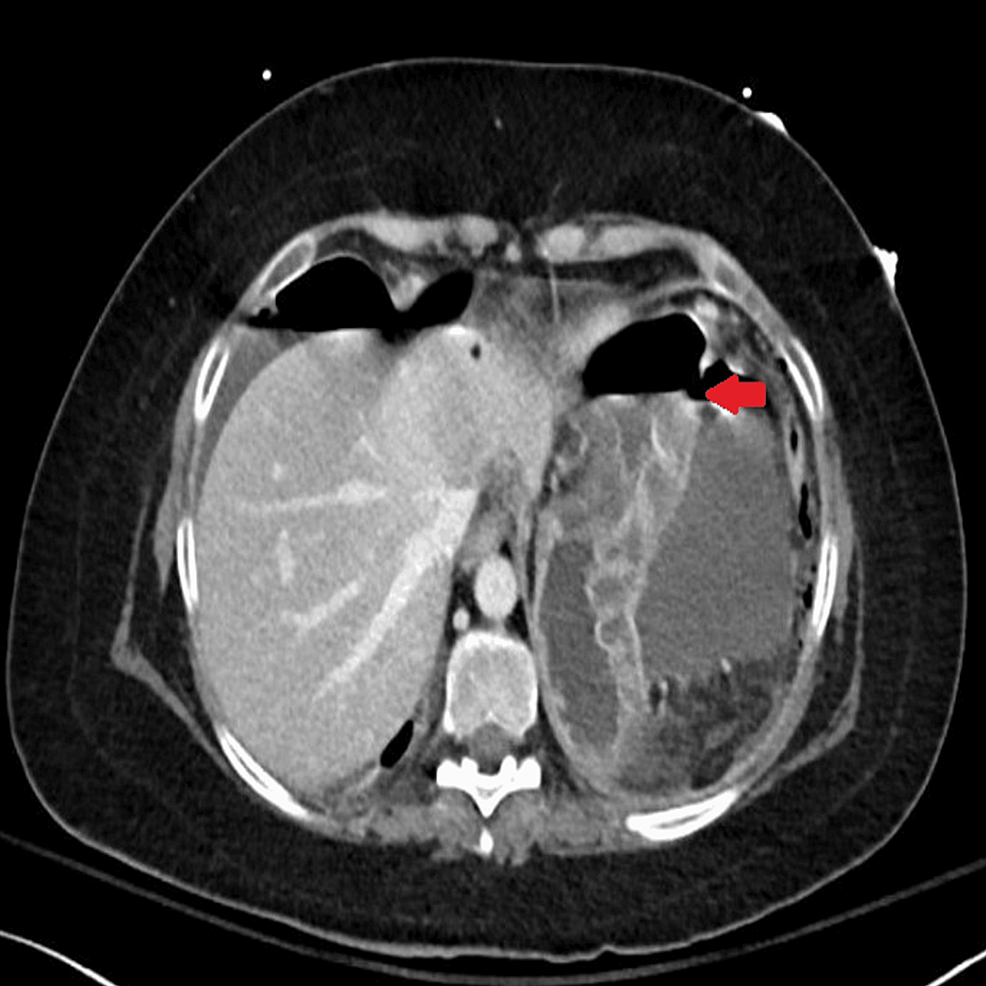

A few days later, the woman experienced a fever, nausea, and headache. These persisted for a few days, and then she started having difficulty breathing. Imaging of her lungs revealed a fluid buildup (pneumonia), and a test for SARS-CoV-2 — the virus that causes COVID-19 — came back positive.

A week after symptoms developed, the patient required supplemental oxygen. Her condition worsened 10 days later, and laboratory tests were indicative of increased inflammation.

To control the patient’s Cushing’s disease, she was treated with increasing doses of metyrapone and similar medications to decrease cortisol production; she was also administered cortisol — this “block and replace” approach aims to maintain cortisol levels within the normal range.

The patient experienced metyrapone side effects that included stomach upset, nausea, dizziness, swelling, increased acne, and hypokalemia (low potassium levels).

She was given antiviral therapies (e.g., favipiravir) to help manage the COVID-19. Additional medications to prevent opportunistic fungal infections were also administered.

From the next day onward, her symptoms eased, and the woman was eventually discharged from the hospital. A month after being discharged, she tested negative for SARS-CoV-2.

Surgery for the pituitary tumor was then again possible. Appropriate safeguards were put in place to protect the medical team caring for her from infection, during and after the surgery.

The patient didn’t have any noteworthy complications from the surgery, and her cortisol levels soon dropped to within normal limits. She was considered to be in remission.

Although broad conclusions cannot be reliably drawn from a single case, the researchers suggested that the patient’s underlying Cushing’s disease may have made her more susceptible to severe pneumonia due to COVID-19.

“Since hypercortisolism due to active Cushing’s disease may enhance the severity of COVID-19 infection, it is necessary to provide appropriate, multidisciplinary and prompt treatment,” the researchers wrote.

Filed under: Cushing's, symptoms, Treatments | Tagged: acne, amenorrhea, buffalo hump, central obesity, COVID-19, Cushing's Disease, dyslipidemia, fat, favipiravir, fever, headache, hypercortisolism, Metyrapone, MRI, nausea, oxygen, Pituitary gland, pneumonia, remission, round face, Weight gain | Leave a comment »