Cushing’s syndrome, or endogenous hypercortisolemia, is a rare condition that both general practice clinicians and endocrinologists should be prepared to diagnose and treat. Including both the pituitary and adrenal forms of the disease, the Endocrine Society estimates that the disorder affects 10 to 15 people per million every year in the United States. It is more common in women and occurs most often in people between the ages of 20 and 50.

Even though Cushing’s remains a rare disease, cortisol recently made waves at the American Diabetes Association 84th Scientific Session. A highlight of the meeting was the initial presentation of data from the CATALYST trial, which assessed the prevalence of hypercortisolism in patients with difficult-to-control type 2 diabetes (A1c 7.5+).

CATALYST is a prospective, Phase 4 study with two parts. In the prevalence phase, 24% of 1,055 enrolled patients had hypercortisolism, defined as an overnight dexamethasone suppression test (ODST) value greater than 1.8 µg/dL and dexamethasone levels greater than 140 µg/dL. Results of CATALYST’s randomized treatment phase are expected in late 2024.

Elena Christofides, MD, FACE, founder of Endocrinology Associates, Inc., in Columbus, OH, believes the CATALYST results will be a wake-up call for both physicians and patients seeking to advocate for their own health. “This means that nearly 1 in 4 patients with type 2 diabetes have some other underlying hormonal/endocrine dysfunction as the reason for their diabetes, or significant contribution to their diabetes, and they should all be screened,” she said. “All providers need to get comfortable with diagnosing and treating hypercortisolemia, and you need to do it quickly because patients are going to pay attention as well.”

In Dr. Christofides’ experience, patients who suspect they have a hormonal issue may start with their primary care provider or they may self-refer to an endocrinologist. “A lot of Cushing’s patients are getting diagnosed and treated in primary care, which is completely appropriate. But I’ve also met endocrinologists who are uncomfortable diagnosing and managing Cushing’s because it is so rare,” she said. “The important thing is that the physician is comfortable with Cushing’s or is willing to put in the work get comfortable with it.”

According to Dr. Christofides, the widespread popular belief that “adrenal fatigue” is causing millions of Americans to feel sick, tired, and debilitated may be creating barriers to care for people who may actually have Cushing’s. “As physicians, we know that adrenal fatigue doesn’t exist, but we should still be receptive to seeing patients who raise that as a concern,” said Dr. Christofides. “We need to acknowledsalige their lived experience as being very real and it can be any number of diseases causing very real symptoms. If we don’t see these patients, real cases of hypercortisolemia could be left undiagnosed and untreated.”

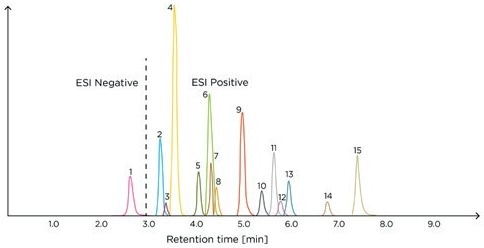

Dr. Christofides, who also serves as a MedCentral Editor-at-Large, said she reminds colleagues that overnight dexamethasone suppression test (ODST) should always be the first test when you suspect Cushing’s. “While technically a screening test, the ODST can almost be considered diagnostic, depending on how abnormal the result is,” she noted. “But I always recommend that you do the ODST, the ACTH, a.m. cortisol, and the DHEAS levels at the same time because it allows you to differentiate more quickly between pituitary and adrenal problems.”

Dr. Christofides does see a place for 24-hour urine collection and salivary cortisol testing at times when diagnosing and monitoring patients with Cushing’s. “The 24-hour urine is only positive in ACTH-driven Cushing’s, so an abnormal result can help you identify the source, but too many physicians erroneously believe you can’t have Cushing’s if the 24-hour urine is normal,” she explained. “Surgeons tend to want this test before they operate and it’s a good benchmark for resolution of pituitary disease.” She reserves salivary cortisol testing for cases when the patient’s ODST is negative, but she suspects Cushing’s may be either nascent or cyclical.

Surgical resection has long been considered first-line treatment in both the pituitary and adrenal forms of Cushing’s. For example, data shared from Massachusetts General Hospital showed that nearly 90% of patients with microadenomas did not relapse within a 30-year period. A recent study found an overall recurrence rate of about 25% within a 10-year period. When reoperation is necessary, remission is achieved in up to 80% of patients.

As new medications for Cushing’s syndrome have become available, Dr. Christofides said she favors medical intervention prior to surgery. “The best part about medical therapy is you can easily stop it if you’re wrong,” she noted. “I would argue that every patient with confirmed Cushing’s deserves nonsurgical medical management prior to a consideration of surgery to improve their comorbidities and surgical risk management, and give time to have a proper informed consent discussion.”

In general, medications to treat Cushing’s disease rely on either cortisol production blockade or receptor blockade, said Dr. Christofides. Medications that directly limit cortisol production include ketoconazole, osilodrostat (Isturisa), mitotane (Lysodren), levoketoconazole (Recorlev), and metyrapone (Metopirone). Mifepristone (Korlym, Mifeprex) is approved for people with Cushing’s who also have type 2 diabetes to block the effects of cortisol. Mifepristone does not lower the amount of cortisol the body makes but limits its effects. Pasireotide (Signifor) lowers the amount of ACTH from the tumor. Cabergoline is sometimes used off-label in the US for the same purpose.

Following surgery, people with Cushing’s need replacement steroids until their adrenal function resumes, when replacement steroids must be tapered. But Dr. Christofides said she believes that all physicians who prescribe steroids should have a clear understanding of when and how to taper patients off steroids.

“Steroid dosing for therapeutic purposes is cumulative in terms of body exposure and the risk of needing to taper. A single 2-week dose of steroids in a year does not require a taper,” she said. “It’s patients who are getting repeated doses of more than 10 mg of prednisone equivalent per day for 2 or more weeks multiple times per year who are at risk of adrenal failure without tapering.”

Physicians often underestimate how long a safe, comfortable taper can take, per Dr. Christofides. “It takes 6 to 9 months for the adrenals to wake up so if you’re using high-dose steroids more frequently, that will cause the patient to need more steroids more frequently,” she explained. “If you’re treating an illness that responds to steroids and you stop them without tapering, the patient’s disease will flare, and then a month from then to 6 weeks from then you’ll be giving them steroids again, engendering a dependence on steroids by doing so.”

When developing a steroid taper plan for postoperative individuals with Cushing’s (and others), Dr. Christofides suggests basing it on the fact that 5 mg of prednisone or its equivalent is the physiologic dose. “Reduce the dose by 5 mg per month until you get to the last 5 mg, and then you’re going to reduce it by 1 mg monthly until done,” she said. “If a patient has difficulty during that last phase, consider a switch to hydrocortisone because a 1 mg reduction of hydrocortisone at a time may be easier to tolerate.”

Prednisone, hydrocortisone, and the other steroids have different half-lives, so you’ll need to plan accordingly, adds Dr. Christofides. “If you do a slower taper using hydrocortisone, the patient might feel worse than with prednisone unless you prescribe it BID.” She suggests thinking of the daily prednisone equivalent of hydrocortisone as 30 mg to allow for divided dosing, rather than the straight 20 mg/day conversion often used.

What happens after a patient’s Cushing’s has been successfully treated? Cushing’s is a chronic disease, even in remission, Dr. Christofides emphasized. “Once you have achieved remission, my general follow-up is to schedule visits every 6 months to a year with scans and labs, always with the instruction if the patient feels symptomatic, they should come in sooner,” she said.

More on Cushing’s diagnosis and therapies.

https://www.medcentral.com/endocrinology/cushings-syndrome-a-clinical-update

Filed under: adrenal, adrenal crisis, Cushing's, Diagnostic Testing, pituitary, Treatments | Tagged: 24-hour urine free cortisol test, ACTH, Adrenal fatigue, cabergoline, CATALYST trial, Cushing's Syndrome, cyclical, dexamethasone suppression test, DHEAS, diabetes, Dr. Elena Christofides, endocrinologist, Endocrinology Associates, hypercortisolism, Isturisa, ketoconazole, Korlym, levoketoconazole, Lysodren, Metopirone, Metyrapone, Mifeprex, mifepristone, mitotane, ODST, Osilodrostat, pasireotide, RECORLEV, salivary test, Signifor, steroids, surgery, taper, UFC, wean | Leave a comment »