Abstract

Background/Objective

Case Presentation

Discussion

Conclusion

Key words

Abbreviations

ACTH

AM

DDAVP

DHEA-S

EAS

ENT

IPSS

ONB

UFC

Highlights

- •

Rare case of ectopic adrenocorticotropic hormone syndrome secondary to olfactory neuroblastoma

- •

Diagnostic challenges highlighted, including nondiagnostic inferior petrosal sinus sampling results

- •

Multidisciplinary approach enabled complete tumor resection and hormonal remission

- •

Preoperative ketoconazole minimized perioperative cortisol-related morbidity

- •

Adjuvant radiotherapy optimized local control in intermediate-risk olfactory neuroblastoma

Clinical Relevance

Introduction

Case Presentation

Diagnostic Assessment

Table 1. Hormone Panel Results

| Test | Value | Normal Range |

|---|---|---|

| AM cortisol | 29 μg/dL (800.11 nmol/L) (high) | 3.7–19.4 μg/dL (102–535 nmol/L) |

| Repeated AM cortisol | 26 μg/dL (717.34 nmol/L) (high) | 3.7–19.4 μg/dL (102–535 nmol/L) |

| ACTH | 250 pg/mL (30.03 pmol/L) (high) | 10–60 pg/mL (2.2–13.2 pmol/L) |

| Plasma renin activity | 1.2 ng/mL/h (1.2 μg/L/h) (normal) | 0.2–4.0 ng/mL/h (0.2–4.0 μg/L/h) |

| DHEA-S | 50 μg/dL (1.25 μmol/L) (low) | 65–380 μg/dL (1.75–10.26 μmol/L) |

| Aldosterone, blood | 4. 9 ng/dL (0.14 nmol/L) (normal) | 4.0–31.0 ng/dL (110–860 pmol/L) |

| Plasma free metanephrines | 0.34 nmol/L (0.034 μg/L) (normal) | <0.50 nmol/L (<0.09 μg/L) |

| Plasma free normetanephrines | 0.75 nmol/L (0.075 μg/L) (normal) | <0.90 nmol/L (<0.16 μg/L) |

| Late-night salivary cortisol (1st) | 0.27 μg/dL (7.45 nmol/L) (high) | ≤0.09 μg/dL (≤2.5 nmol/L) (10 PM–1 AM) |

| Late-night salivary cortisol (2nd) | 0.36 μg/dL (9.93 nmol/L) (high) | ≤0.09 μg/dL (≤2.5 nmol/L) (10 PM–1 AM) |

| 24-h urinary free cortisol (1st) | 5880.0 μg/d (16 223 nmol/d) (high) | ≤60.0 μg/d (≤165 nmol/d) |

| 24-h urinary free cortisol (2nd) | 4920.0 μg/d (13 576 nmol/d) (high) | ≤60.0 μg/d (≤165 nmol/d) |

| AM cortisol level (after 1 mg dexamethasone) | 12.3 μg/dL (339 nmol/L) (high) | <1.8 μg/dL (<50 nmol/L) adequate suppression |

| Dexamethasone level(after 1 mg dexamethasone) | 336 ng/dL (8.64 nmol/L) (normal) | >200 ng/dL (>5.2 nmol/L) adequate absorption |

| ACTH level (after 1 mg dexamethasone) | 242 pg/mL (53.27 pmol/L) (not suppressed) | 10–60 pg/mL (2.2–13.2 pmol/L) |

Table 2. Bilateral Petrosal Sinus and Peripheral Adrenocorticotropin Levels Before and After Intravenous Injection of Desmopressin Acetate (DDAVP) 10 mcg

| Time post DDAVP, min | Left petrosal ACTH | Left: peripheral ACTH | Right petrosal ACTH | Right: peripheral ACTH | Peripheral ACTH | Left: right petrosal ACTH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 165 pg/mL (36.3 pmol/L) | 1.1 | 160 pg/mL (35.2 pmol/L) | 1.1 | 150 pg/mL (33.0 pmol/L) | 1.03 |

| 3 | 270 pg/mL (59.4 pmol/L) | 1.6 | 245 pg/mL (53.9 pmol/L) | 1.4 | 170 pg/mL (37.4 pmol/L) | 1.10 |

| 5 | 320 pg/mL (70.4 pmol/L) | 1.7 | 285 pg/mL (62.7 pmol/L) | 1.5 | 185 pg/mL (40.7 pmol/L) | 1.12 |

| 10 | 350 pg/mL (77.0 pmol/L) | 1.4 | 305 pg/mL (67.2 pmol/L) | 1.2 | 250 pg/mL (55.0 pmol/L) | 1.15 |

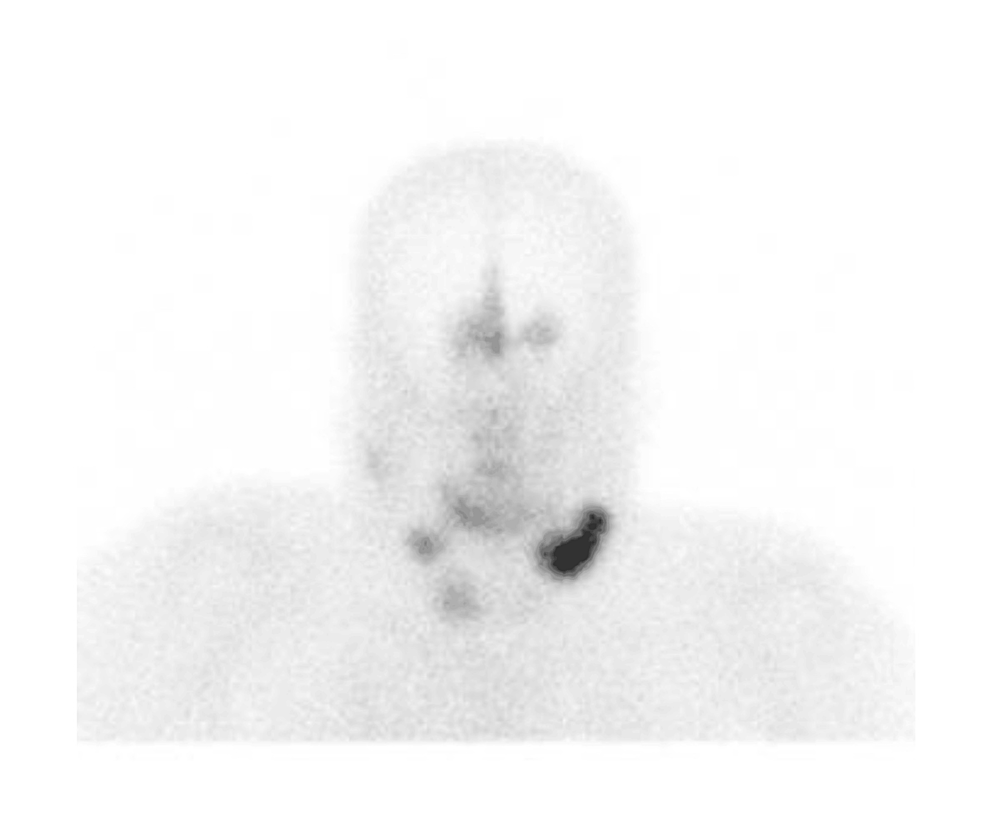

Fig. 1. (A) Axial and (B) coronal noncontrast computed tomography (CT) images of the head demonstrate a heterogeneous soft tissue mass at the anterior skull base extending toward the cribriform plate and into the right nasal cavity, involving the ethmoid sinus and eroding the lamina papyracea, resulting in medial displacement of the right orbital contents (blue arrows). (C) Axial contrast-enhanced CT of the abdomen reveals bilateral adrenal gland enlargement. (D) Whole-body single-photon emission computed tomography/computed tomography (SPECT/CT) using indium-111 pentetreotide demonstrates intense radiotracer uptake localized to the biopsy-confirmed esthesioneuroblastoma in the ethmoid sinuses, with no evidence of metastatic octreotide-avid lesions. (G) Coronal contrast-enhanced CT scan of the abdomen, performed after surgery, shows normalization in the size of both adrenal glands. (E) Coronal and (F) axial noncontrast CT images of the paranasal sinuses obtained postoperatively demonstrate complete surgical resection of the tumor.

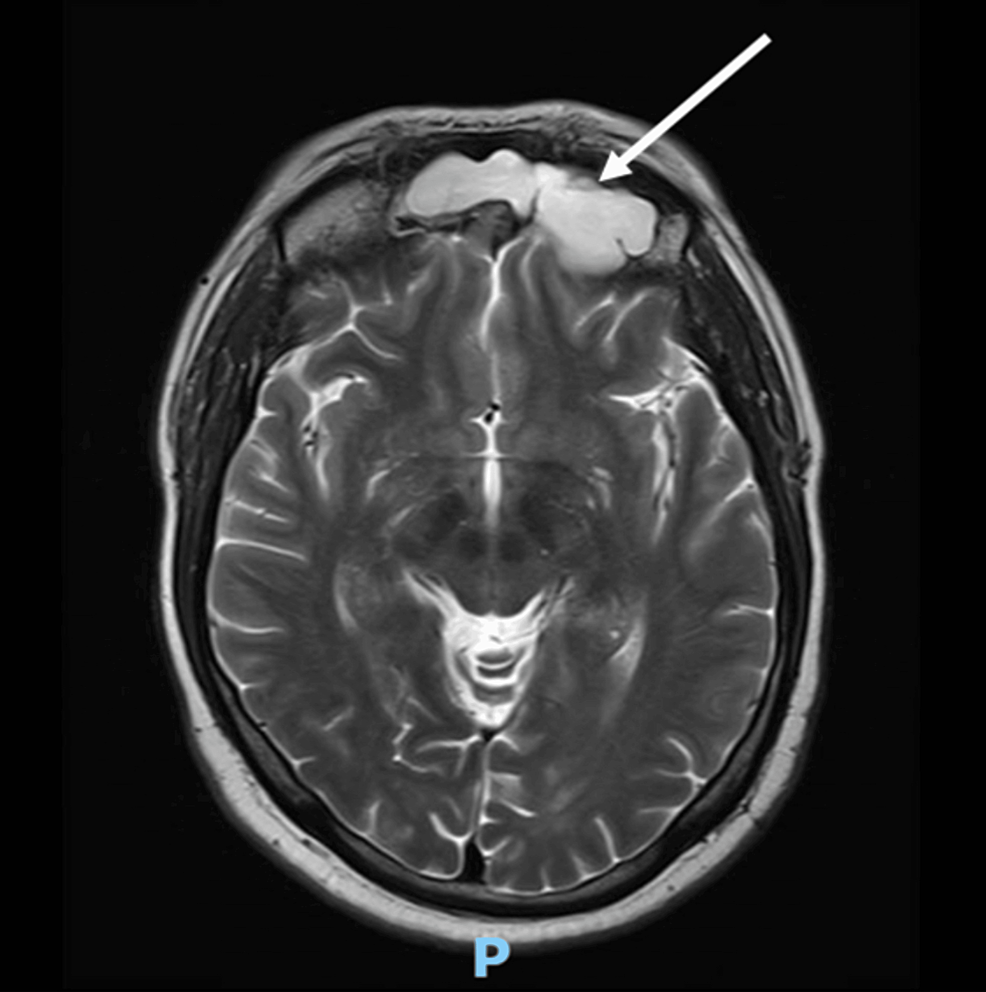

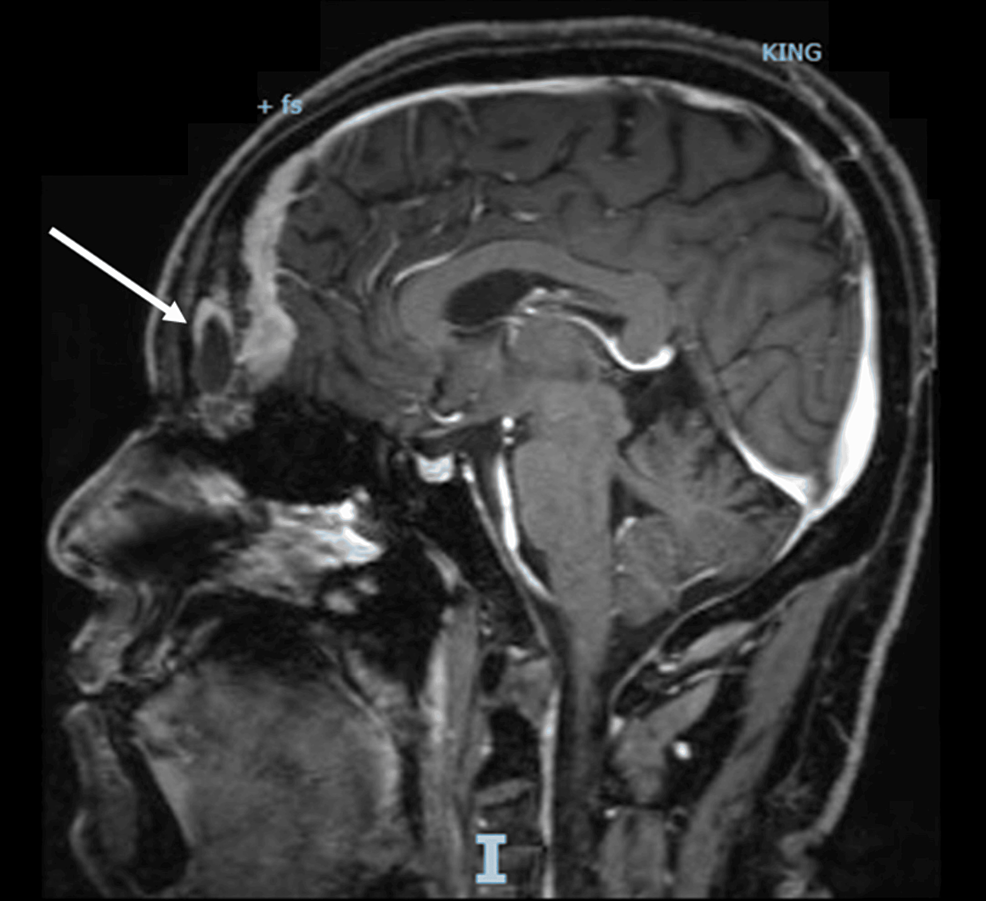

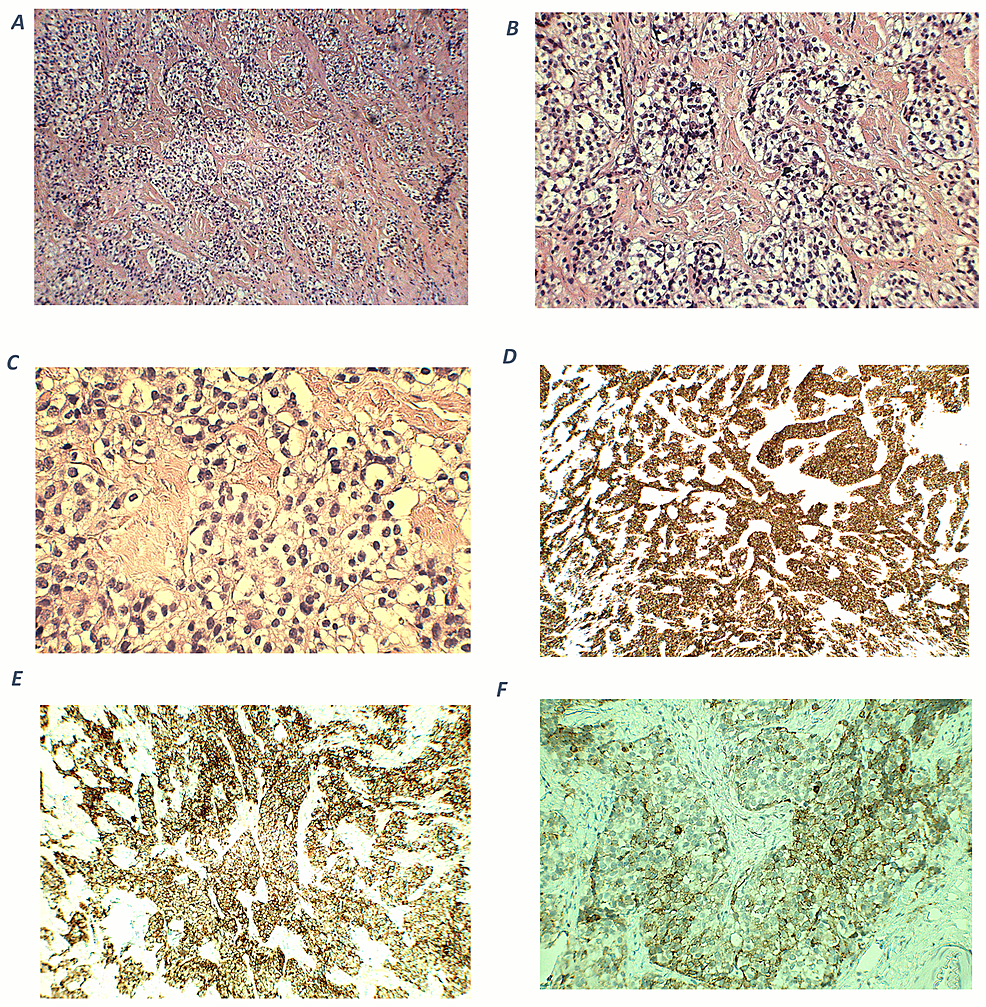

Fig. 2. (A) Low-power H&E (4×) shows well-circumscribed lobules of small round blue cells with fibrovascular stroma and a neurofibrillary matrix; no necrosis or rosettes are seen. (B) High-power H&E (40×) reveals neoplastic cells with high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio, hyperchromatic nuclei, and granular chromatin, consistent with Hyams Grade 2 ONB. (C) Chromogranin A shows granular cytoplasmic positivity in tumor nests, confirming neuroendocrine differentiation. (D) Synaptophysin shows diffuse granular cytoplasmic staining in tumor clusters, with negative stromal background. (E) S-100 highlights sustentacular cells in a peripheral pattern around tumor nests. (F) ACTH staining shows patchy to diffuse cytoplasmic positivity in tumor cells, confirming ectopic ACTH production in ONB. A nuclear medicine octreotide scan (111 Indium-pentetreotide scintigraphy) with single-photon emission computed tomography/computed tomography (SPECT/CT) demonstrated intense radiotracer uptake in the biopsy-proven esthesioneuroblastoma centered within the ethmoid sinuses, confirming the tumor’s expression of somatostatin receptors. There was no evidence of locoregional or distant metastatic disease demonstrating octreotide avidity (Fig. 1D).

Treatment

Outcome and Follow-Up

Table 3. Timeline of Clinical and Biochemical Recovery Following Resection of Ectopic ACTH-Secreting Olfactory Neuroblastoma

| Parameter | Preoperative value | 24–48 h Postop | 2 wks postop | 3 mo postop | Normal range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blood pressure | 171/84 mmHg | 140/80 mmHg | 124/78 mmHg | 122/76 mmHg | <130/80 mmHg |

| Fasting glucose | 244 mg/dL (13.5 mmol/L) | 160 mg/dL (8.9 mmol/L) | 95 mg/dL (5.3 mmol/L) | 90 mg/dL (5.0 mmol/L) | 70–99 mg/dL (3.9–5.5 mmol/L) |

| Potassium | 1.6 mEq/L (1.6 mmol/L) | 3.8 mEq/L (3.8 mmol/L) | 4.3 mEq/L (4.3 mmol/L) | 4.2 mEq/L (4.2 mmol/L) | 3.5–5.0 mEq/L (3.5–5.0 mmol/L) |

| ACTH | 220–250 pg/mL (48.4–55.2 pmol/L) | <10 pg/mL (<2.2 pmol/L) | 29 pg/mL (5.5 pmol/L) | 25 pg/mL (4.9 pmol/L) | 10–60 pg/mL (2.2–13.3 pmol/L) |

| AM cortisol | 29 μg/dL (800 nmol/L) | <5 μg/dL (<138 nmol/L) | 12 μg/dL (331 nmol/L) | 15 μg/dL (414 nmol/L); Cosyntropin peak: 21 μg/dL (580 nmol/L) | 5–25 μg/dL (138–690 nmol/L); adequate response >18 μg/dL (500–550 nmol/L) |

| LNSC | 0.27/0.36 μg/dL (7.45/9.93 nmol/L) | — | — | 0.04/0.03 μg/dL (1.10/0.83 nmol/L) | ≤0.09 μg/dL (≤2.5 nmol/L) (10 PM–1 AM) |

| UFC (24-h) | 5880/4920 μg/d (16 223/13 576 nmol/d) | — | — | 38 μg/d (105 nmol/d) | ≤60 μg/d (≤165 nmol/d) |

| Cushing’s Stigmata | Moon facies, dorsocervical fat pad, violaceous striae, severe muscle weakness | No change | Partial improvement: BP/glucose control; decreased edema | Marked improvement; muscle strength restored; striae fading | Not applicable |

Discussion

Diagnostic Considerations

Therapeutic Approach and Challenges

Prognosis and Future Directions

Conclusion

Statement of Patient Consent

Disclosure

References

- 1

L.K. Nieman, B.M. Biller, J.W. Findling, et al.The diagnosis of cushing’s syndrome: an endocrine society clinical practice guidelineJ Clin Endocrinol Metab, 93 (5) (2008), pp. 1526-1540, 10.1210/jc.2008-0125

- 2

A.M. Isidori, A. LenziEctopic ACTH syndromeArq Bras Endocrinol Metabol, 51 (8) (2007), pp. 1217-1225, 10.1590/s0004-27302007000800007

- 3

M. Kadoya, M. Kurajoh, A. Miyoshi, et al.Ectopic adrenocorticotropic hormone syndrome associated with olfactory neuroblastomaJ Int Med Res, 46 (12) (2018), pp. 4760-4768, 10.1177/0300060517754026

- 4

L.D. ThompsonOlfactory neuroblastomaHead Neck Pathol, 3 (3) (2009), pp. 252-259, 10.1007/s12105-009-0125-2

- 5

M.E. Platek, M. Merzianu, T.L. Mashtare, et al.Improved survival following surgery and radiation therapy for olfactory neuroblastoma: analysis of the SEER databaseRadiat Oncol, 6 (2011), p. 41, 10.1186/1748-717X-6-41

- 6

J.B. Finlay, R. Abi Hachem, D.W. Jang, N. Osazuwa-Peters, B.J. GoldsteinDeconstructing olfactory epithelium developmental pathways in olfactory neuroblastomaCancer Res Commun, 3 (4) (2023), pp. 980-990, 10.1158/2767-9764.CRC-23-0013

- 7

Z. Yin, Y. Wang, Y. Wu, et al.Age distribution and age-related outcomes of olfactory neuroblastoma: a population-based analysisCancer Manag Res, 10 (2018), pp. 1359-1364, 10.2147/CMAR.S151945

- 8

O. ChabreCushing syndrome: physiopathology, etiology and principles of therapy[French] Presse Med, 43 (4 Pt 1) (2014), pp. 376-392, 10.1016/j.lpm.2014.02.001

- 9

J. Rimmer, V.J. Lund, T. Beale, et al.Olfactory neuroblastoma: a 35-year experience and suggested follow-up protocolLaryngoscope, 124 (7) (2014), pp. 1542-1549

- 10

K. Clotman, M.T.B. Twickler, E. Dirinck, et al.An endocrine picture in disguise: a progressive olfactory neuroblastoma complicated with ectopic cushing syndromeAACE Clin Case Rep, 3 (4) (2017), pp. 278-283

- 11

M. Kunc, A. Gabrych, P. Czapiewski, K. SworczakParaneoplastic syndromes in olfactory neuroblastomaContemp Oncol (Pozn), 19 (1) (2015), pp. 6-16, 10.5114/wo.2015.46283

- 12

M.B. Lopes, R. Fonseca, J.F. Serôdio, R.P. Oliveira, J.D. AlvesEctopic adrenocorticotropic hormone syndrome due to olfactory neuroblastoma: a case report and literature reviewEndocrinol Diabetes Nutr (Engl Ed, 72 (6) (2025), Article 501576, 10.1016/j.endien.2024.08.006

- 13

S. Yener, C. Aydin, B. Akinci, et al.DHEAS for the prediction of subclinical Cushing’s syndrome: perplexing or advantageous?Endocrine, 49 (3) (2015), pp. 823-831, 10.1007/s12020-014-0387-7

- 14

B.P. Hauffa, B. Weber, W.D. MatternDissociation between plasma adrenal androgens and cortisol in Cushing’s disease and ectopic ACTH-producing tumourLancet, 323 (8391) (1984), pp. 137-140, 10.1016/S0140-6736(84)91873-7

- 15

D. Khawandanah, E.J. Stohs, Y.S. Elhassan, W.F. Young Jr.Adrenal function after resection of adrenal adenomas in Cushing’s syndrome and incidentalomasEndocrine, 64 (2) (2019), pp. 323-331, 10.1007/s12020-018-1769-z

- 16

E.A. Japp, E.L. Alba, A.C. LevineEctopic ACTH syndromeA.C. Levine (Ed.), A Case-Based Guide to Clinical Endocrinology, Springer (2022), pp. 285-289, 10.1007/978-3-030-84367-0_20

- 17

Y. Zhi, S.E. Serfling, D. Groener, et al.Somatostatin receptor–directed theranostics in esthesioneuroblastomaClin Nucl Med, 50 (5) (2025), pp. 363-367, 10.1097/RLU.0000000000004871

- 18

M. Reznik, J. Melon, M. Lambricht, B. Kaschten, A. BeckersNeuroendocrine tumor of the nasal cavity (esthesioneuroblastoma). Apropos of a case with paraneoplastic cushing’s syndrome[French] Ann Pathol, 7 (3) (1987), pp. 137-142

- 19

D. Elkon, S.I. Hightower, M.L. Lim, R.W. Cantrell, W.C. ConstableEsthesioneuroblastomaCancer, 44 (3) (1979), pp. 1087-1094, 10.1002/1097-0142(197909)44:3<1087::aid-cncr2820440343>3.0.co;2-a

Filed under: Cushing's, Rare Diseases | Tagged: Adrenocorticotropic Hormone (ACTH)-Dependent, Cushing's Syndrome, ectopic, Epistaxis, facial rounding, hypertension, hypokalemia, Inferior petrosal sinus sampling, IPSS, muscle weakness, olfactory neuroblastoma, Weight gain | Leave a comment »