ISTURISA® (osilodrostat) is indicated for the treatment of adult patients with Cushing’s disease who have persistent or recurrent hypercortisolism after primary pituitary surgery and/or irradiation, or for whom pituitary surgery is not an option.1

TORONTO, Jan. 13, 2026 /CNW/ – Recordati Rare Diseases Canada Inc. announced today the Canadian product availability of ISTURISA® (osilodrostat) for the treatment of adult patients with Cushing’s disease who have persistent or recurrent hypercortisolism following pituitary surgery and/or irradiation, or for whom surgery is not an option.1 This is following the marketing authorisation of ISTURISA® in Canada on July 5, 2025.

Dr. André Lacroix, Professor of Medicine at the University of Montreal and internationally recognized authority in Cushing’s syndrome, commented on the importance of this new treatment option: ” ISTURISA® is an important addition to the treatment options for Cushing’s disease, a rare and debilitating condition. Achieving control of cortisol overproduction is an important strategy in helping patients manage Cushing’s disease.”

ISTURISA’s approval is supported by data from the LINC 3 and LINC 4 Phase III clinical studies, which demonstrated clinically meaningful reductions in mean urinary free cortisol (mUFC) levels and showed a favourable safety profile. ISTURISA® is available as 1 mg, 5 mg, and 10 mg film-coated tablets, enabling individualized titration based on cortisol levels and clinical response.1

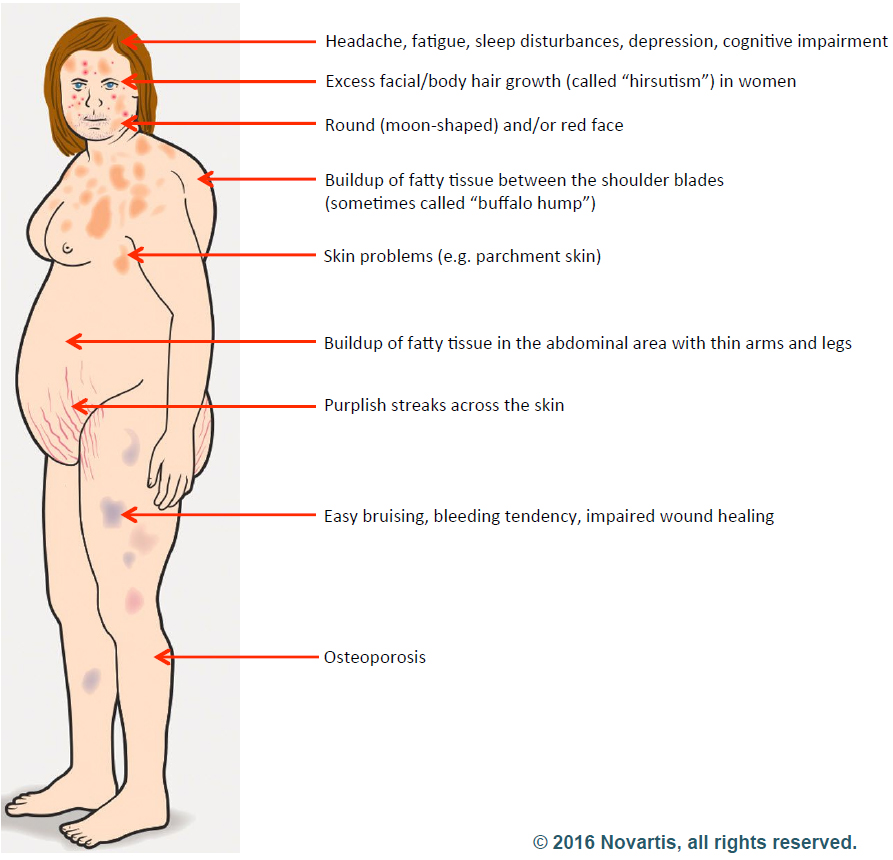

About Cushing’s Disease

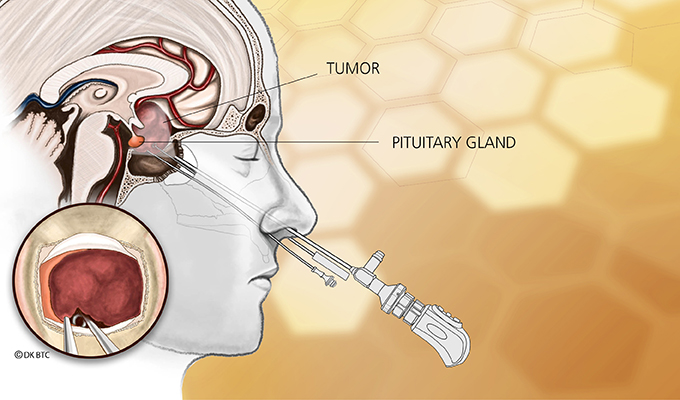

Cushing disease is a rare disorder of hypercortisolism caused by an adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)-secreting pituitary adenoma, which in turn stimulates the adrenal glands to produce excess cortisol. Prolonged exposure to elevated cortisol levels is associated with substantial morbidity and mortality and impaired quality of life (QoL). Accordingly, normalization of cortisol is the primary treatment goal for Cushing disease.2

About Isturisa®

ISTURISA® is an inhibitor of 11β‐hydroxylase (CYP11B1), the enzyme responsible for the final step of cortisol synthesis in the adrenal gland. ISTURISA® is taken twice daily and is available as 1 mg, 5 mg and 10 mg film‐coated tablets, allowing for individualized titration based on cortisol levels and clinical response. For full prescribing information, healthcare professionals are encouraged to consult the Isturisa Product Monograph at https://recordatirarediseases.com/wp content/uploads/2025/08/ISTURISAProduct-Monograph-English-Current.pdf

Recordati Rare Diseases is Recordati’s dedicated business unit focused on rare diseases. Recordati is an international pharmaceutical Group listed on the Italian Stock Exchange (XMIL: REC), with roots dating back to a family-run pharmacy in Northern Italy in the 1920s. Our fully integrated operations span clinical development, chemical and finished product manufacturing, commercialisation and licensing. We operate in approximately 150 countries across EMEA, the Americas and APAC with over 4,500 employees.

Recordati Rare Diseases’ mission is to reduce the impact of extremely rare and devastating diseases by providing urgently needed therapies. We work side-by-side with rare disease communities to increase awareness, improve diagnosis and expand availability of treatments for people with rare diseases.

Recordati Rare Diseases Canada Inc. is the company’s Canada offices located inToronto, Ontario, with the North America headquarter offices located in New Jersey, US, and the global headquarter offices located in Milan, Italy.

This document contains forward-looking statements relating to future events and future operating, economic and financial results of the Recordati group. By their nature, forward-looking statements involve risk and uncertainty because they depend on the occurrence of future events and circumstances. Actual results may therefore differ materially from those forecast for a variety of reasons, most of which are beyond the Recordati group’s control. The information on the pharmaceutical specialties and other products of the Recordati group contained in this document is intended solely as information on the activities of the Recordati Group, and, as such, it is not intended as a medical scientific indication or recommendation, or as advertising.

| References: |

| 1. Isturisa® Product Monograph. 2025-07-03 |

| 2. Gadelha M et al. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2022 Jun 16;107(7): e2882-e2895 |

SOURCE Recordati Rare Diseases Canada Inc.

Media Relations: spPR Inc., Sonia Prashar, 416.560.6753, Soniaprashar@sppublicrelations.com

Filed under: Cushing's, pituitary, Treatments | Tagged: Canada, Dr. André Lacroix, Isturisa, Osilodrostat, pituitary, radiation, recurrence, surgery | Leave a comment »