Minimally invasive diagnostic methods and transnasal surgery may lead to remission in nearly all children with Cushing’s disease, while avoiding more aggressive approaches such as radiation or removal of the adrenal glands, a study shows.

The study, “A personal series of 100 children operated for Cushing’s disease (CD): optimizing minimally invasive diagnosis and transnasal surgery to achieve nearly 100% remission including reoperations,” was published in the Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism.

Normally, the pituitary produces adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), which stimulates the adrenal glands to produce cortisol. When a patient has a pituitary tumor, that indirectly leads to high levels of cortisol, leading to development of Cushing’s disease (CD).

In transnasal surgery (TNS), a surgeon goes through the nose using an endoscope to remove a pituitary tumor. The approach is the first-choice treatment for children with Cushing’s disease due to ACTH-secreting adenomas — or tumors — in the pituitary gland.

Micro-adenomas, defined as less than 4 mm, are more common in children and need surgical expertise for removal. It is necessary to determine the exact location of the tumor before conducting the surgery.

Additionally, many surgeons perform radiotherapy or bilateral adrenalectomy (removal of both adrenal glands) after the surgery. However, these options are not ideal as they can be detrimental to children who need to re-establish normal growth and development patterns.

Dieter K. Lüdecke, a surgeon from Germany’s University of Hamburg, has been able to achieve nearly 100% remission while minimizing the need for pituitary radiation or bilateral adrenalectomy. In this study, researchers looked at how these high remission rates can be achieved while minimizing radiotherapy or bilateral adrenalectomy.

Researchers analyzed 100 patients with pediatric CD who had been referred to Lüdecke for surgery from 1980-2009. Data was published in two separate series — series 1, which covers patients from 1980-1995, and series 2, which covers 1996-2009. All the surgeries employed direct TNS.

Diagnostic methods for CD have improved significantly over the past 30 years. Advanced endocrine diagnostic investigations, such as testing for levels of salivary cortisol in the late evening and cortisol-releasing hormone tests, have made a diagnosis of CD less invasive. This is particularly important for excluding children with obesity alone from children with obesity and CD. Methods to determine the precise location of micro-adenomas have also improved.

The initial methodology to localize tumors was known as inferior petrosal sinus sampling (IPSS), an invasive procedure in which ACTH levels are sampled from the veins that drain the pituitary gland.

In series 1, IPSS was performed in 24% of patients, among which 46% were found to have the wrong tumor location. Therefore, IPSS was deemed invasive, risky, and unreliable for this purpose.

All adenomas were removed with extensive pituitary exploration. Two patients in series 1 underwent early repeat surgery; all were successful.

Lüdecke introduced intraoperative cavernous sinus sampling (CSS), an improved way to predict location of adenomas. This was found to be very helpful in highly select cases and could also be done preoperatively for very small adenomas.

In series 2, CSS was used in only 15% of patients thanks to improved MRI and endocrinology tests. All patients who underwent CSS had correct localization of their tumors, indicating its superiority over IPSS.

In series 2, three patients underwent repeat TNS, which was successful. In these recurrences, TNS minimized the need for irradiation. The side effects of TNS were minimal. Recurrence rate in series 1 was 16% and 11% in series 2.

While Lüdecke’s patients achieved a remission rate of 98%, other studies show cure rates of 45-69%. Only 4% of patients in these two series received radiation therapy.

“Minimally invasive unilateral, microsurgical TNS is important functionally for both the nose and pituitary,” the researchers concluded. “Including early re-operations, a 98% remission rate could be achieved and the high risk of pituitary function loss with radiotherapy could be avoided.”

From https://cushingsdiseasenews.com/2018/09/04/minimally-invasive-methods-yield-high-remission-in-cushings-disease-children/

Filed under: Cushing's, pituitary, Treatments | Tagged: ACTH, children, Inferior petrosal sinus sampling, IPSS, pituitary, remission, transnasal | Leave a comment »

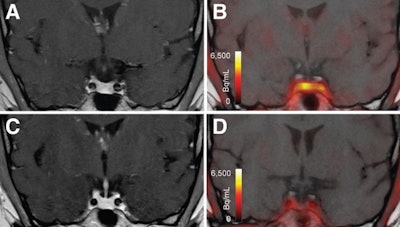

T1-weighted postgadolinium MR images (A and C) and F-18 FET-PET/MR images (B and D) centered at pituitary before (A and B) and after (C and D) transsphenoidal surgery. This patient with Cushing disease showed clear focal uptake (B) but no clear lesion on previously obtained and accompanying MRI (A). Postoperative tissue analysis did confirm resection of small pituitary adenoma/PitNET, and postoperative F-18 FET-PET showed no residual uptake (D). Image courtesy of the Journal of Nuclear Medicine.

T1-weighted postgadolinium MR images (A and C) and F-18 FET-PET/MR images (B and D) centered at pituitary before (A and B) and after (C and D) transsphenoidal surgery. This patient with Cushing disease showed clear focal uptake (B) but no clear lesion on previously obtained and accompanying MRI (A). Postoperative tissue analysis did confirm resection of small pituitary adenoma/PitNET, and postoperative F-18 FET-PET showed no residual uptake (D). Image courtesy of the Journal of Nuclear Medicine. View Full Size

View Full Size View Full Size

View Full Size View Full Size

View Full Size