ESTES PARK, COLO. – Diabetes mellitus, osteoporosis, and hypertension are conditions that should boost the index of suspicion that a patient with some cushingoid features may in fact have endogenous Cushing’s syndrome, Dr. Michael T. McDermott said at a conference on internal medicine sponsored by the University of Colorado.

An estimated 1 in 20 patients with type 2 diabetes has endogenous Cushing’s syndrome. The prevalence of this form of hypercortisolism is even greater – estimated at up to 11% – among individuals with osteoporosis. In hypertensive patients, the figure is 1%. And among patients with an incidentally detected adrenal mass, it’s 6%-9%, according to Dr. McDermott, professor of medicine and director of endocrinology and diabetes at the University of Colorado.

“Endogenous Cushing’s syndrome is not rare. I suspect I’ve seen more cases than I’ve diagnosed,” he observed. “I’ve probably missed a lot because I failed to screen people, not recognizing that they had cushingoid features. Not everyone looks classic.”

There are three screening tests for endogenous Cushing’s syndrome that all primary care physicians ought to be familiar with: the 24-hour urine cortisol test, the bedtime salivary cortisol test, and the overnight 1-mg dexamethasone suppression test.

“I think if you have moderate or mild suspicion, you should use one of these tests. If you have more than moderate suspicion – if a patient really looks like he or she has Cushing’s syndrome – then I would use at least two screening tests to rule out endogenous Cushing’s syndrome,” the endocrinologist continued.

The patient performs the bedtime salivary cortisol test at home, obtaining samples two nights in a row and mailing them to an outside laboratory. The overnight dexamethasone suppression test entails taking 1 mg of dexamethasone at bedtime, then measuring serum cortisol the next morning. A value greater than 1.8 mcg/dL is a positive result.

Pregnant women constitute a special population for whom the screening method recommended in Endocrine Society clinical practice guidelines (J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2008;93:1526-40) is the 24-hour urine cortisol test. That’s because pregnancy is a state featuring high levels of cortisol-binding globulins, which invalidates the other tests. In patients with renal failure, the recommended screening test is the 1-mg dexamethasone suppression test. In patients on antiepileptic drugs, the 24-hour urine cortisol or bedtime salivary cortisol test is advised, because antiseizure medications enhance the metabolism of dexamethasone.

Dr. McDermott said that “by far” the most discriminatory clinical features of endogenous Cushing’s syndrome are easy bruising, violaceous striae on the trunk, facial plethora, and proximal muscle weakness.

“They’re by no means specific. You’ll see these features in people who don’t have Cushing’s syndrome. But those are the four things that should make you really consider Cushing’s syndrome in your differential diagnosis,” he stressed.

More widely recognized yet actually less discriminatory clinical features include facial fullness and the “buffalo hump,” supraclavicular fullness, central obesity, hirsutism, reduced libido, edema, and thin or poorly healing skin.

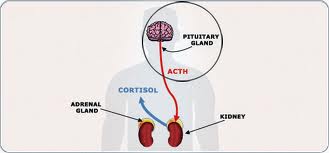

Endogenous Cushing’s syndrome can have three causes. An adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)-secreting pituitary adenoma accounts for 80% of cases. A cortisol-secreting adrenal tumor is the cause of 10%. And another 10% are due to an ectopic ACTH-secreting tumor, most commonly a bronchial carcinoid tumor.

Once the primary care physician has a positive screening test in hand, it’s typical to refer the affected patient to an endocrinologist in order to differentiate which of the three causes is present. This is accomplished based upon the results of a large, 8-mg dexamethasone suppression test coupled with measurement of plasma ACTH levels.

Dr. McDermott recommended as a good read on the topic of evaluating a patient with endogenous Cushing’s syndrome a recent review article that included a useful algorithm (N. Engl. J. Med. 2013;368:2126-36).

He reported having no financial conflicts.

bjancin@frontlinemedcom.com

From http://www.clinicalendocrinologynews.com

Filed under: adrenal, Cancer, Cushing's, pituitary, Rare Diseases | Tagged: 24-hour urine free cortisol test, ACTH, adrenal tumor, Adrenocorticotropic hormone, bronchial carcinoid tumor, bruising, buffalo hump, Cushing, Cushing Syndrome, dexamethasone suppression test, diabetes mellitus, Dr, edema, Endocrine Society, endogenous, hirsuitism, hypertension, Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, libido, Michael T. McDermott, moon face, muscle weakness, obesity, osteoporosis, pituitary tumor, pregnancy, salivary cortisol, stretch marks, striae, thin skin, Type 2 diabetes, UFC | Leave a comment »