Abstract

Background

Bilateral inferior petrosal sinus sampling (BIPSS) is important in the differential diagnosis of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)-dependent Cushing’s syndrome, but BIPSS is invasive and is not reliable on tumor lateralization. Thus, we evaluated the noninvasive diagnostic evaluations, high-dose dexamethasone suppression test (HDDST) combined with different pituitary MRI scans (conventional contrast-enhanced MRI [cMRI], dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI [dMRI], and high-resolution contrast-enhanced MRI [hrMRI]), by comparison with BIPSS.

Methods

We retrospectively analyzed 95 patients with ACTH-dependent Cushing’s syndrome who underwent HDDST, preoperative MRI scans (cMRI, dMRI and hrMRI) and BIPSS in our hospital between January 2016 and December 2021. The diagnostic performance of HDDST combined with cMRI (HDDST + cMRI), HDDST + dMRI and HDDST + hrMRI, and BIPSS was evaluated, including the sensitivity of identifying pituitary adenomas and the tumor lateralization accuracy.

Results

Compared with BIPSS (AUC, 0.98; 95%CI: 0.93, 1.00), the diagnostic performance of HDDST + hrMRI was comparable in both neuroradiologist 1 (AUC, 0.95; 95%CI: 0.89, 0.99; P = 0.129) and neuroradiologist 2 (AUC, 0.98; 95%CI: 0.92, 1.00; P = 0.707). For tumor lateralization accuracy, HDDST + hrMRI (90.6-95.3%) were significantly higher than that of BIPSS (24.7%, P < 0.001).

Conclusions

In patients with ACTH-dependent Cushing’s syndrome, HDDST + hrMRI, as noninvasive diagnostic evaluations, achieves high diagnostic performance comparable with gold standard (BIPSS), and it is superior to BIPSS in terms of tumor lateralization accuracy.

Background

Cushing’s syndrome is associated with debilitating morbidity and increased mortality [1]. Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)-dependent Cushing’s syndrome is characterized by ACTH hypersecretion. Bilateral inferior petrosal sinus sampling (BIPSS) is regarded as the gold standard to distinguish pituitary ACTH secretion (also known as Cushing’s disease) from ectopic ACTH syndrome (EAS) [1, 2]. However, BIPSS is invasive and is not reliable on tumor lateralization [3, 4]. Thus, it is important to improve the diagnostic performance of noninvasive evaluations with high sensitivity and tumor lateralization accuracy.

Current noninvasive evaluations in the differential diagnosis of ACTH-dependent Cushing’s syndrome include high-dose dexamethasone suppression test (HDDST), the CRH stimulation test and pituitary MRI. However, due to the non-availability of CRH for testing, the sensitivities of current available noninvasive evaluations in identifying ACTH-secreting pituitary adenomas cannot satisfy the clinical needs. Conventional contrast-enhanced MRI (cMRI) and dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI (dMRI) with two-dimensional (2D) fast spin echo (FSE) sequence is routinely used, and only 50–66% of the ACTH-secreting pituitary adenomas can be correctly detected [5, 6]. Recently, by using 3D spoiled gradient recalled (SPGR) sequence, high-resolution contrast-enhanced MRI (hrMRI) has increased the sensitivity to up to 80% [7,8,9]. However, these noninvasive evaluations are still inferior to BIPSS, the sensitivity and specificity of which is about 90–95% [10,11,12,13]. With the development of 3D FSE sequence, superior image quality with diminished artifact has been achieved, providing a reliable alternative to detect pituitary adenomas [14]. Previous studies have shown that hrMRI using 3D FSE sequence has high diagnostic performance for identifying pituitary adenomas [15, 16]. To our knowledge, no study has investigated the diagnostic performance of HDDST combined with hrMRI using 3D FSE sequence (HDDST + hrMRI) in patients with Cushing’s syndrome, and whether it can avoid unnecessary BIPSS procedure.

The aim of this study is to evaluate the diagnostic performance of HDDST + hrMRI by comparison with BIPSS in patients with ACTH-dependent Cushing’s syndrome.

Methods

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Institutional Review Board of Peking Union Medical College Hospital. Informed consent was waived in this study because it was a retrospective, non-interventional, and observational study. Clinical trial number is not applicable.

Study design and patient population

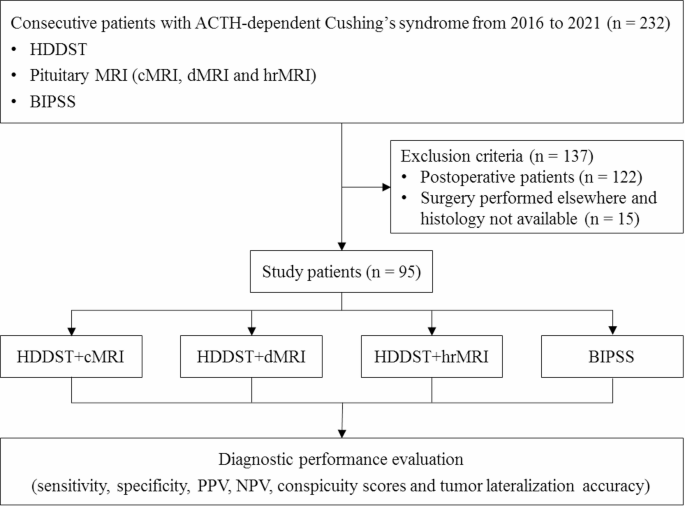

We retrospectively reviewed the medical records and imaging studies from January 2016 to December 2021, and 232 consecutive patients with ACTH-dependent Cushing’s syndrome, who underwent HDDST, cMRI, dMRI, hrMRI and BIPSS, were enrolled in the current study. A total of 137 patients were excluded from the study because of prior pituitary surgery (n = 122) or lack of histopathology due to no pituitary surgery in our hospital (n = 15). Finally, 95 patients were included in the current study (Fig. 1) and all the patients included were confirmed by histopathology or by clinical remission after surgical resection of the ACTH-secreting lesion. In the current study, all the patients with Cushing’s disease achieved clinical remission after surgical resection of the ACTH-secreting lesion. All the patients with EAS underwent contrast-enhanced thoracic and abdominal CT to identify the ACTH-secreting lesion. The clinical decision-making process was consistent with the previous study [1].

Flowchart of patient inclusion/exclusion process. ACTH = adrenocorticotropic hormone, BIPSS = bilateral inferior petrosal sinus sampling; cMRI = conventional contrast-enhanced MRI, dMRI = dynamic enhanced MRI, HDDST = high-dose dexamethasone suppression test, hrMRI = high-resolution contrast-enhanced MRI, NPV = negative predictive value, PPV = positive predictive value

HDDST

As previously described [17], the average 24-hour urinary free cortisol (24hUFC) level of 2 days before HDDST was recorded as baseline. Then, 2 mg dexamethasone was administered orally every 6 h for 2 days, and the 24hUFC level of the second day was measured. When the ratio of 24hUFC on the second day after HDDST to 24hUFC at baseline was less than 50%, the suppression in HDDST was marked as positive in the current study.

BIPSS

BIPSS was performed according to Doppman et al. [18]. Blood samples were collected from peripheral veins and bilateral inferior petrosal sinuses (IPSs) at multiple time points (0, 3, 5 and 10 min) after the introduction of 10 µg desmopressin [19]. An IPS to peripheral ACTH ratio of ≥ 2.0 at baseline or ≥ 3.0 after desmopressin stimulation at any time point [20] was marked as positive in the current study. Furthermore, tumor lateralization was predicted by an intersinus ratio of ≥ 1.4 [20].

Imaging

All the images were acquired on a 3.0 Tesla MR scanner (Discovery MR750w, GE Healthcare) using an 8-channel head coil. Detailed acquisition parameters and sequence order before and after contrast injection (gadopentetate dimeglumine [Gd-DTPA] at 0.05 mmol/kg [0.1 mL/kg] with a flow rate of 2 mL/s followed by a 10-mL saline solution flush) were as follows: coronal 2D FSE T2WI (field of view [FOV] = 20 cm × 20 cm, slice thickness = 4 mm, slice spacing = 1 mm, repetition time/echo time [TR/TE] = 4100/90 ms, number of excitation [NEX] = 1.2, matrix = 320 × 320, scan time = 49s), coronal 2D FSE T1WI (FOV = 18 cm × 16.2 cm, slice thickness = 3 mm, slice spacing = 0.6 mm, TR/TE = 400/12 ms, NEX = 2, matrix = 256 × 192, scan time = 49s), sagittal fat-saturated 3D FSE T1WI (FOV = 16.5 cm × 16.5 cm, slice thickness = 3 mm, slice spacing = 0, TR/TE = 460/16 ms, NEX = 2, matrix = 256 × 224, scan time = 60s), dynamic contrast-enhanced coronal 2D FSE T1WI (FOV = 19 cm × 17.1 cm, slice thickness = 2 mm, slice spacing = 0.5 mm, TR/TE = 375/14 ms, NEX = 1, matrix = 288 × 192, scan time = 23s/phase × 6 phases), contrast-enhanced coronal 2D FSE T1WI, contrast-enhanced sagittal fat-saturated 3D FSE T1WI, and contrast-enhanced coronal fat-saturated 3D FSE T1WI (FOV = 15.2 cm × 15.2 cm, slice thickness = 1.2 mm, slice spacing = -0.6 mm, TR/TE = 390/15 ms, NEX = 6, matrix = 256 × 256, scan time = 4 min 30s).

Images were independently evaluated by two experienced neuroradiologists (with 25 and 16 years of experience in neuroradiology, respectively). Both neuroradiologists were blinded to the clinical information of the patients. The image order of cMRI, dMRI and hrMRI was randomized. The detection of pituitary adenomas was scored using a 3-point scale (0 = poor, 1 = fair, 2 = excellent). Scores of 1 or 2 represented a successful pituitary adenoma detection. The gold standard was the histopathology, and the diameter and the location of lesions were recorded on the sequence where identified.

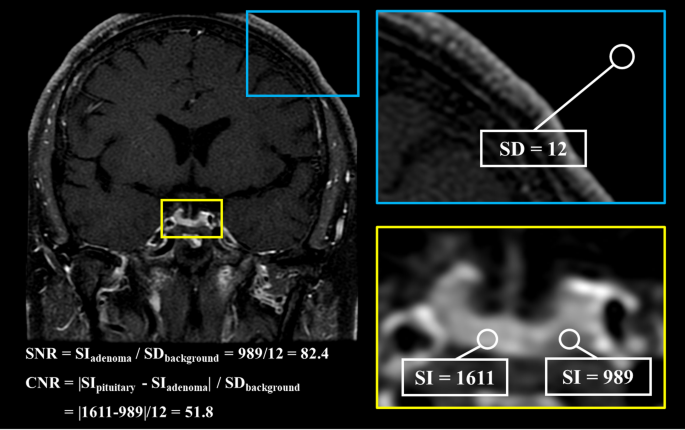

The signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) and contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) were calculated as follows: SNR = SIadenoma / SDbackground, CNR = |SIpituitary – SIadenoma| / SDbackground. SIpituitary and SIadenoma were defined as the mean signal intensity of the pituitary gland and the pituitary adenoma, respectively. SDbackground was defined as the standard deviation of the signal intensity of the background. CNR was recorded as 0 when no pituitary adenoma was identified. Figure 2 showed the calculation of SNR and CNR using an operator defined region of interest.

The calculation of SNR and CNR using an operator defined region of interest. CNR = contrast-to-noise ratio, SD = standard deviation, SI = signal intensity, SNR = signal-to-noise ratio

Statistical analysis

The κ analysis was conducted to assess the interobserver agreements. The κ value was interpreted as follows: below 0.20, slight agreement; 0.21–0.40, fair agreement; 0.41–0.60, moderate agreement; 0.61–0.80, substantial agreement; greater than 0.80, almost perfect agreement.

To assess the diagnostic performance of different evaluations, the receiver operating characteristic curves were plotted and the area under curves (AUCs) were compared between noninvasive and invasive evaluations for each neuroradiologist by using the DeLong test. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value were calculated. The Friedman’s test was used to evaluate the SNR and CNR measurements as well as conspicuity scores of pituitary adenomas between MR protocols, and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used for pairwise comparison. The McNemar’s test was used to evaluate the tumor lateralization accuracy. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. A stricter P value of less than 0.017 was considered statistically significant after Bonferroni correction. Statistical analysis was performed using MedCalc Statistical Software (version 23.0.2) and SPSS Statistics (version 22.0).

Results

Clinical characteristics

The clinical characteristics of the 95 patients with Cushing’s syndrome were shown in Table 1. There were 85 patients (median age, 38 years; interquartile range [IQR], 29–51 years; 55 females [65%]) with Cushing’s disease and 10 patients (median age, 39 years; IQR, 30–47 years; 5 females [50%]) with EAS. Of the 85 patients with Cushing’s disease, the median diameter of pituitary adenomas was 5 mm (IQR, 4–5 mm), ranging from 3 to 28 mm. Among them, 80 patients had microadenomas (less than 10 mm in size). Of the ten patients with EAS, one patient had an ovarian carcinoid tumor found by abdominal CT, others had pulmonary carcinoid tumors found by thoracic CT as the cause of Cushing’s syndrome. None of the patients with EAS had a lesion in the pituitary.

Diagnostic performance noninvasive and invasive evaluations

The inter-observer agreements between two neuroradiologists were moderate on cMRI (κ = 0.597), moderate on dMRI (κ = 0.595), and almost perfect on hrMRI (κ = 0.850), respectively.

The diagnostic performance of noninvasive and invasive evaluations was shown in Table 2. Compared with BIPSS (AUC, 0.98; 95%CI: 0.93, 1.00), the diagnostic performance of HDDST + hrMRI was comparable in both neuroradiologist 1 (AUC, 0.95; 95%CI: 0.89, 0.99; P = 0.129) and neuroradiologist 2 (AUC, 0.98; 95%CI: 0.92, 1.00; P = 0.707). However, the diagnostic performance of HDDST + cMRI and HDDST + dMRI was inferior to BIPSS (P ≤ 0.001 for all). No difference was found between HDDST + cMRI and HDDST + dMRI in neuroradiologist 1 (P = 0.050) and neuroradiologist 2 (P = 0.353).

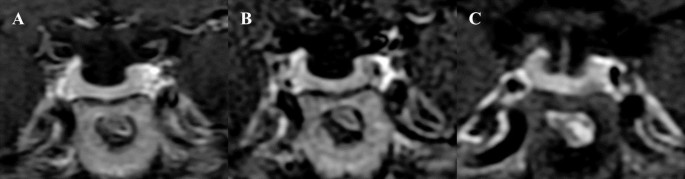

Figures 3 and 4 showed that microadenomas were correctly diagnosed on hrMRI, but missed on cMRI or dMRI.

Images in a patient with Cushing’s disease. The lesion is missed on (a) coronal contrast-enhanced T1-weighted image and (b) coronal dynamic contrast-enhanced T1-weighted image obtained with two-dimensional (2D) fast spin echo (FSE) sequence. (c) Coronal contrast-enhanced T1-weighted image on high-resolution MRI obtained with 3D FSE sequence shows a round pituitary microadenoma measuring approximately 4 mm with delayed enhancement on the left side of the pituitary gland

Images in a patient with Cushing’s disease. The lesion is missed on (a) coronal contrast-enhanced T1-weighted image and (b) coronal dynamic contrast-enhanced T1-weighted image obtained with two-dimensional (2D) fast spin echo (FSE) sequence. (c) Coronal contrast-enhanced T1-weighted image on high-resolution MRI obtained with 3D FSE sequence shows a round pituitary microadenoma measuring approximately 5 mm with delayed enhancement on the left side of the pituitary gland

Further, subgroup analysis was conducted in 85 patients with Cushing’s disease. The conspicuity scores of pituitary adenomas on cMRI, dMRI and hrMRI were shown in Table 3. Significant differences between three MR protocols were found in neuroradiologist 1 and neuroradiologist 2 (P < 0.001 for both). Pairwise comparison showed no difference between cMRI and dMRI in neuroradiologist 1 (P = 0.732) and neuroradiologist 2 (P = 0.130). However, hrMRI had significantly higher scores than cMRI and dMRI in neuroradiologist 1 and neuroradiologist 2 (P < 0.001 for all). The SNR on cMRI, dMRI and hrMRI were 64.8 (IQR, 50.8–97.0), 42.4 (IQR, 30.2–57.0) and 65.1 (IQR, 51.9–92.4), respectively. The SNR on cMRI and hrMRI were similar (P = 0.759), but they were higher than that of dMRI (P < 0.001 for both). The CNR on cMRI, dMRI and hrMRI were27.0 (IQR, 17.8–43.8), 26.4 (IQR, 17.7–37.5), and 29.7 (IQR, 21.1–45.1), respectively. The CNR were comparable (P = 0.159).

The comparison of tumor lateralization accuracy was shown in Table 4. Because HDDST has no role to identify the tumor lateralization, the tumor lateralization of noninvasive evaluations was only based on MRI. The sensitivity of BIPSS was 96.5% (82/85), comparable to those of hrMRI in neuroradiologist 1 (90.6%, P = 0.227) and neuroradiologist 2 (95.3%, P > 0.99). However, for tumor lateralization accuracy, 36 patients had BIPSS lateralization predicted by an intersinus ratio of ≥ 1.4 [20], and 21 patients had BIPSS lateralization that were concordant in laterality with surgery. The tumor lateralization accuracy was 58.3% (21/36).

In the whole population, the tumor lateralization accuracy of BIPSS in total was 24.7% (21/85), which is significantly lower than those of hrMRI in neuroradiologist 1 (90.6%, P < 0.001) and neuroradiologist 2 (95.3%, P < 0.001).

Discussion

In patients with ACTH-dependent Cushing’s syndrome, it is crucial but challenging to distinguish pituitary secretion from ectopic ACTH secretion. In the current study, the diagnostic performance of noninvasive evaluations, HDDST + hrMRI, is comparable to BIPSS. Moreover, it is superior to BIPSS in terms of tumor lateralization.

No consensus agreement has been made that whether BIPSS should be performed in all the patients with suspected Cushing’s disease, although BIPSS is the gold standard with high sensitivity and specificity, which is about 90–95% [10,11,12,13]. On the one hand, about 10–40% of the population harbor nonfunctioning pituitary adenomas [13, 21], which may lead to false-positive results without centralizing BIPSS results. On the other hand, BIPSS is invasive and is not reliable on tumor lateralization. BIPSS will be bypassed when the tumor is greater than 6 mm in pituitary MRI and the patient has a classical presentation and dynamic biochemical results consistent with Cushing’s disease [13].

Noninvasive evaluations have comparable sensitivity to BIPSS for identifying pituitary adenomas in patients with Cushing’s disease. With the development of MRI technology, 3D FSE sequence provides a reliable alternative to detect pituitary adenomas [14]. The 3D FSE sequence overcomes the disadvantages of 3D SPGR sequence, such as bright blood and magnetic susceptibility [22, 23]. By using black blood in 3D FSE sequence, an obvious contrast between the pituitary and the cavernous sinus can be observed. By using fat saturation after enhancement, the hyperintensity of adjacent fat-containing tissue can be suppressed. All these mentioned above can facilitating the identification of pituitary adenomas. The sensitivity of hrMRI using 3D FSE sequence ranges from 87.7 to 93.8%, depending on radiologists with different experience levels [16]. Compared with traditional 2D FSE sequence acquiring images with 2- to 3-mm slice thickness, hrMRI using 3D FSE sequence acquiring images with 1.2-mm slice thickness can dramatically reduce the partial volume averaging effect, improving the identification of the microadenomas [15]. The trade-off between spatial resolution and image noise is challenging in pituitary MRI [24]. Previous studies have proved that hrMRI has high signal-to-noise ratio and contrast-to-noise ratio [15, 16], and sufficient contrast between pituitary adenomas and the pituitary gland could help to improve the identification of pituitary adenomas. In the current study, the conspicuity scores of hrMRI are significantly higher than those of cMRI and dMRI, supporting that hrMRI is reliable on identifying pituitary lesions. Besides, the diagnosis of Cushing’s disease cannot be made depending on the results of hrMRI alone. Given that there is a population with accidental adenomas when imaging, most of which are nonfunctioning pituitary adenomas, the results of HDDST will help rule out. In the current study, all the patients who underwent surgery had positive histopathology results, which means that no pituitary incidentalomas were found in this population. This might be caused by the relatively small sample size. Eighty patients with Cushing’s disease have microadenomas, and the median diameter at surgery is about 5 mm, consistent with previous studies [25, 26]. All these mentioned above makes it more difficult to identify the lesions in the current study. However, the sensitivity of HDDST + hrMRI in the current study is up to 95.3%, comparable to the gold standard.

Noninvasive evaluations have significantly higher tumor lateralization accuracy than BIPSS. According to the guideline, surgery is the first-line treatment [3]. Precise location of the pituitary adenoma before surgery can dramatically improve the postoperative remission rate [27]. However, the tumor lateralization accuracy of BIPSS, less than 80% in previous studies [19, 28, 29], cannot satisfy the clinical need. According to previous studies, the cut-off value for tumor lateralization was set as an intersinus ratio of ≥ 1.4 [20], and the accuracy of lateralization by BIPSS ranged from 48.0 to 78.7% [19, 28, 29]. In the current study, 36 patients had BIPSS lateralization and 21 patients had BIPSS lateralization that were concordant in laterality with surgery. The tumor lateralization accuracy was 58.3%, consistent with previous studies [19, 28, 29]. However, the aim of our study is to evaluate the diagnostic performance of BIPSS in all the patients underwent BIPSS, therefore, the tumor lateralization accuracy of BIPSS in total was only 24.7% (21/85). In our study, many patients have positive BIPSS results with an intersinus ratio of < 1.4, resulting in the low tumor lateralization accuracy of BIPSS. One possible reason might be that desmopressin is not so effective. Another possible reason for low tumor lateralization accuracy of BIPSS is that IPSs have considerable anatomy variations. A previous study suggests that BIPSS results are much improved when venous drainage is symmetric [30]. Patients with asymmetric IPSs have dominant venous drainage, and when the dominant side of venous drainage is discordant with the side of the lesion, BIPSS will fail in tumor lateralization [30]. Failure in tumor lateralization will result in multiple incisions into the pituitary in search of adenoma or hemi- or subtotal hypophysectomy, increasing the risk of complications and reducing the remission rate [31]. In total, only 24.7% of the patients have a BIPSS lateralization that were concordant in laterality with surgery, whereas the tumor lateralization accuracy of HDDST + hrMRI is superior to BIPSS with statistical significance.

Limitations of the study included its retrospective nature. The bias may be introduced during the patient inclusion/exclusion process. Patients lack of any of preoperative MRI scans, HDDST, or BIPSS have not been included in the current study. Some patients will bypass hrMRI as well as BIPSS when they have obvious pituitary adenomas on cMRI and dMRI. The diagnostic performance of these evaluations might be better with the inclusion of these patients. Second, the sample size in our current study is relatively small. Because this is a single institutional study and Cushing’s syndrome is a rare disease. The relatively small sample size may limit the conclusions regarding the diagnostic performance of hrMRI for differentiating ectopic from pituitary sources of ACTH. A larger population from multicenter is needed for future study. Besides, a large portion of patients with prior pituitary surgery have been excluded. The imaging findings of these patients are more complicated and hrMRI may show more advantages than routine sequences in this population.

Conclusions

In conclusion, as noninvasive diagnostic evaluations, HDDST + hrMRI achieves high diagnostic performance comparable with gold standard (BIPSS), and it is superior to BIPSS in terms of tumor lateralization accuracy in patients with ACTH-dependent Cushing’s syndrome.

Data availability

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- 24hUFC:

- 24-hour urinary free cortisol

- 2D:

- Two-dimensional

- 3D:

- Three-dimensional

- ACTH:

- Adrenocorticotropic hormone

- AUC:

- Area under curve

- BIPSS:

- Bilateral inferior petrosal sinus sampling

- cMRI:

- Contrast-enhanced MRI

- CNR:

- Contrast-to-noise ratio

- dMRI:

- Dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI

- EAS:

- Ectopic adrenocorticotropic hormone syndrome

- FSE:

- Fast spin echo

- HDDST:

- High-dose dexamethasone suppression test

- hrMRI:

- High-resolution contrast-enhanced MRI

- IPS:

- Inferior petrosal sinus

- IQR:

- Interquartile range

- SNR:

- Signal-to-noise ratio

- SPGR:

- Spoiled gradient recalled

References

-

Lacroix A, Feelders RA, Stratakis CA, Nieman LK. Cushing’s syndrome. Lancet (London England). 2015;386(9996):913–27.

-

Loriaux DL. Diagnosis and differential diagnosis of cushing’s syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(15):1451–9.

-

Nieman LK, Biller BM, Findling JW, Murad MH, Newell-Price J, Savage MO, et al. Treatment of cushing’s syndrome: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(8):2807–31.

-

Wind JJ, Lonser RR, Nieman LK, DeVroom HL, Chang R, Oldfield EH. The lateralization accuracy of inferior petrosal sinus sampling in 501 patients with cushing’s disease. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(6):2285–93.

-

Boscaro M, Arnaldi G. Approach to the patient with possible cushing’s syndrome. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(9):3121–31.

-

Kasaliwal R, Sankhe SS, Lila AR, Budyal SR, Jagtap VS, Sarathi V, et al. Volume interpolated 3D-spoiled gradient echo sequence is better than dynamic contrast spin echo sequence for MRI detection of Corticotropin secreting pituitary microadenomas. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2013;78(6):825–30.

-

Grober Y, Grober H, Wintermark M, Jane JA, Oldfield EH. Comparison of MRI techniques for detecting microadenomas in cushing’s disease. J Neurosurg. 2018;128(4):1051–7.

-

Fukuhara N, Inoshita N, Yamaguchi-Okada M, Tatsushima K, Takeshita A, Ito J, et al. Outcomes of three-Tesla magnetic resonance imaging for the identification of pituitary adenoma in patients with cushing’s disease. Endocr J. 2019;66(3):259–64.

-

Patronas N, Bulakbasi N, Stratakis CA, Lafferty A, Oldfield EH, Doppman J, Nieman LK. Spoiled gradient recalled acquisition in the steady state technique is superior to conventional Postcontrast spin echo technique for magnetic resonance imaging detection of adrenocorticotropin-secreting pituitary tumors. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(4):1565–9.

-

Pecori Giraldi F, Cavallo LM, Tortora F, Pivonello R, Colao A, Cappabianca P, et al. The role of inferior petrosal sinus sampling in ACTH-dependent cushing’s syndrome: review and joint opinion statement by members of the Italian society for endocrinology, Italian society for neurosurgery, and Italian society for neuroradiology. NeuroSurg Focus. 2015;38(2):E5.

-

Biller BM, Grossman AB, Stewart PM, Melmed S, Bertagna X, Bertherat J, et al. Treatment of adrenocorticotropin-dependent cushing’s syndrome: a consensus statement. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(7):2454–62.

-

Newell-Price J, Bertagna X, Grossman AB, Nieman LK. Cushing’s syndrome. Lancet (London England). 2006;367(9522):1605–17.

-

Arnaldi G, Angeli A, Atkinson AB, Bertagna X, Cavagnini F, Chrousos GP, et al. Diagnosis and complications of cushing’s syndrome: a consensus statement. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(12):5593–602.

-

Sartoretti T, Sartoretti E, Wyss M, Schwenk A, van Smoorenburg L, Eichenberger B, et al. Compressed SENSE accelerated 3D T1w black blood turbo spin echo versus 2D T1w turbo spin echo sequence in pituitary magnetic resonance imaging. Eur J Radiol. 2019;120:108667.

-

Liu Z, Hou B, You H, Lu L, Duan L, Li M, et al. High-resolution contrast-enhanced MRI with three-dimensional fast spin echo improved the diagnostic performance for identifying pituitary microadenomas in cushing’s syndrome. Eur Radiol. 2023;33(9):5984–92.

-

Liu Z, Hou B, You H, Lu L, Duan L, Li M, et al. Three-Dimensional fast spin echo pituitary MRI in Treatment-Naive cushing’s disease: reduced impact of reader experience and increased diagnostic accuracy. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2024;59(6):2115–23.

-

Liu Z, Zhang X, Wang Z, You H, Li M, Feng F, Jin Z. High positive predictive value of the combined pituitary dynamic enhanced MRI and high-dose dexamethasone suppression tests in the diagnosis of cushing’s disease bypassing bilateral inferior petrosal sinus sampling. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):14694.

-

Doppman JL, Oldfield E, Krudy AG, Chrousos GP, Schulte HM, Schaaf M, Loriaux DL. Petrosal sinus sampling for Cushing syndrome: anatomical and technical considerations. Work in progress. Radiology. 1984;150(1):99–103.

-

Machado MC, de Sa SV, Domenice S, Fragoso MC, Puglia P Jr., Pereira MA, et al. The role of Desmopressin in bilateral and simultaneous inferior petrosal sinus sampling for differential diagnosis of ACTH-dependent cushing’s syndrome. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2007;66(1):136–42.

-

Oldfield EH, Doppman JL, Nieman LK, Chrousos GP, Miller DL, Katz DA, et al. Petrosal sinus sampling with and without corticotropin-releasing hormone for the differential diagnosis of cushing’s syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1991;325(13):897–905.

-

Chong BW, Kucharczyk W, Singer W, George S. Pituitary gland MR: a comparative study of healthy volunteers and patients with microadenomas. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1994;15(4):675–9.

-

Lien RJ, Corcuera-Solano I, Pawha PS, Naidich TP, Tanenbaum LN. Three-Tesla imaging of the pituitary and parasellar region: T1-weighted 3-dimensional fast spin echo cube outperforms conventional 2-dimensional magnetic resonance imaging. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2015;39(3):329–33.

-

Kakite S, Fujii S, Kurosaki M, Kanasaki Y, Matsusue E, Kaminou T, Ogawa T. Three-dimensional gradient echo versus spin echo sequence in contrast-enhanced imaging of the pituitary gland at 3T. Eur J Radiol. 2011;79(1):108–12.

-

Kim M, Kim HS, Kim HJ, Park JE, Park SY, Kim YH, et al. Thin-Slice pituitary MRI with deep Learning-based reconstruction: diagnostic performance in a postoperative setting. Radiology. 2021;298(1):114–22.

-

Vitale G, Tortora F, Baldelli R, Cocchiara F, Paragliola RM, Sbardella E, et al. Pituitary magnetic resonance imaging in cushing’s disease. Endocrine. 2017;55(3):691–6.

-

Jagannathan J, Smith R, DeVroom HL, Vortmeyer AO, Stratakis CA, Nieman LK, Oldfield EH. Outcome of using the histological pseudocapsule as a surgical capsule in Cushing disease. J Neurosurg. 2009;111(3):531–9.

-

Yamada S, Fukuhara N, Nishioka H, Takeshita A, Inoshita N, Ito J, Takeuchi Y. Surgical management and outcomes in patients with Cushing disease with negative pituitary magnetic resonance imaging. World Neurosurg. 2012;77(3–4):525–32.

-

Deipolyi A, Bailin A, Hirsch JA, Walker TG, Oklu R. Bilateral inferior petrosal sinus sampling: experience in 327 patients. J Neurointerv Surg. 2017;9(2):196–9.

-

Castinetti F, Morange I, Dufour H, Jaquet P, Conte-Devolx B, Girard N, Brue T. Desmopressin test during petrosal sinus sampling: a valuable tool to discriminate pituitary or ectopic ACTH-dependent cushing’s syndrome. Eur J Endocrinol. 2007;157(3):271–7.

-

Lefournier V, Martinie M, Vasdev A, Bessou P, Passagia JG, Labat-Moleur F, et al. Accuracy of bilateral inferior petrosal or cavernous sinuses sampling in predicting the lateralization of cushing’s disease pituitary microadenoma: influence of catheter position and anatomy of venous drainage. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88(1):196–203.

-

Castle-Kirszbaum M, Amukotuwa S, Fuller P, Goldschlager T, Gonzalvo A, Kam J, et al. MRI for Cushing disease: A systematic review. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2023;44(3):311–6.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Kai Sun, Medical Research Center, Peking Union Medical College Hospital, for his guidance on the statistical analysis in this study. We thank all the patients who participated in this study.

Funding

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grants 82371946 and 82071899), the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (grant 2021-I2M-1-025), and the National High Level Hospital Clinical Research Funding (grants 2022-PUMCH-B-067 and 2022-PUMCH-B-114). The funding played no role in the design of the study and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript.

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Institutional Review Board of Peking Union Medical College Hospital. Informed consent was waived by Institutional Review Board of Peking Union Medical College Hospital, because it was a retrospective, non-interventional, and observational study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Z., Hou, B., You, H. et al. Improved noninvasive diagnostic evaluations in treatment-naïve adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)-dependent Cushing’s syndrome. BMC Med Imaging 25, 252 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12880-025-01786-y

- Received

- Accepted

- Published

- DOI https://doi.org/10.1186/s12880-025-01786-y

https://bmcmedimaging.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12880-025-01786-y

Filed under: Cushing's, Diagnostic Testing | Tagged: ACTH, Bilateral inferior petrosal sinus sampling, BIPSS, dexamethasone suppression test, MRI, pituitary | Leave a comment »