Abstract

Here, we present the case of a 40-year-old man in whom the diagnosis of ectopic adrenocorticotropin (ACTH) syndrome went unrecognized despite evaluation by multiple providers until it was ultimately suspected by a nephrologist evaluating the patient for edema and weight gain. On urgent referral to endocrinology, screening for hypercortisolism was positive by both low-dose overnight dexamethasone suppression testing and 24-hour urinary free cortisol measurement. Plasma ACTH values confirmed ACTH-dependent Cushing syndrome. High-dose dexamethasone suppression testing was suggestive of ectopic ACTH syndrome. Inferior petrosal sinus sampling demonstrated no central-to-peripheral gradient, and 68Ga-DOTATATE scanning revealed an avid 1.2-cm left lung lesion. The suspected source of ectopic ACTH was resected and confirmed by histopathology, resulting in surgical cure. While many patients with Cushing syndrome have a delayed diagnosis, this case highlights the critical need to increase awareness of the signs and symptoms of hypercortisolism and to improve the understanding of appropriate screening tests among nonendocrine providers.

Introduction

Even in the face of overt clinical signs and symptoms of hypercortisolism, diagnosing Cushing syndrome requires a high index of suspicion, and people with hypercortisolism experience a long road to diagnosis. In a recent meta-analysis including more than 5000 patients with Cushing syndrome, the mean time to diagnosis in all Cushing syndrome, including Cushing disease and ectopic adrenocorticotropin (ACTH) syndrome, was 34 months (1). Reasons for delayed diagnosis are multifactorial, including the nonspecific nature of subjective symptoms and objective clinical signs, as well as notorious challenges in the interpretation of diagnostic testing. Furthermore, the health care system’s increasingly organ-specific referral patterns obfuscate multisystem disorders. Improving the recognition of and decreasing time to diagnosis in Cushing syndrome are critical factors in reducing morbidity and mortality.

Here, we present the case of a patient who, despite classic signs of Cushing syndrome as well as progressive physical and mental decline, remained undiagnosed for more than 3 years while undergoing repeated evaluation by primary care and subspecialty providers. The case (1) highlights the lack of awareness of Cushing syndrome as a potential unifying diagnosis for multiorgan system problems; (2) underscores the necessity of continued education on the signs and symptoms of hypercortisolism, appropriate screening for hypercortisolism, and early referral to endocrinology; and (3) provides an opportunity for systemic change in clinical laboratory practice that could help improve recognition of pathologic hypercortisolism.

Case Presentation

In August 2018, a previously healthy 40-year-old man with ongoing tobacco use established care with a primary care provider complaining that he had been ill since the birth of his son 13 months prior. He described insomnia, headaches, submandibular swelling, soreness in his axillary and inguinal regions, and right-sided chest discomfort (Fig. 1). Previously, he had been diagnosed with sinusitis, tonsillitis, and allergies, which had been treated with a combination of antibiotics, antihistamines, and intranasal glucocorticoids. He was referred to otolaryngology where, in the absence of cervical lymphadenopathy, he was diagnosed with sternocleidomastoid pain with recommendations to manage conservatively with stretching and massage. A chest x-ray demonstrated a left apical lung nodule. Symptoms continued unabated throughout 2019, now with a cough. Repeat chest x-ray demonstrated opacities lateral to the left hilum that were attributed to vascular structures.

Figure 1.

Timeline of development of subjective symptoms and objective clinical findings preceding diagnosis and surgical cure of ectopic Cushing syndrome.

In May 2020, increasingly frustrated with escalating symptoms, the patient transitioned care to a second primary care provider and was diagnosed with hypertension. He complained of chronic daily headaches that prompted brain imaging with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which noted findings consistent with left maxillary silent sinus syndrome. He was sent back to otolaryngology, which elected to proceed with sinus surgery. During this time, he suffered a fibular fracture for which he was evaluated by orthopedic surgery. In the second half of 2020, he was seen by neurology to evaluate his chronic headaches and paresthesias with electromyography demonstrating a left ulnar mononeuropathy consistent with cubital tunnel syndrome. His primary care provider diagnosed him with fibromyalgia for which he started physical therapy, and he was referred to a pain clinic for cognitive behavioral therapy. Unfortunately his wife, dealing with her husband’s increasing cognitive and personality changes including irritability and aggression, filed for divorce.

At the end of 2020, the patient developed bilateral lower extremity edema and was prescribed hydrochlorothiazide, subsequently developing hypokalemia attributed to diuretic use. With worsening bilateral lower extremity edema and new dyspnea on exertion, he was evaluated for heart failure with an echocardiogram, which was unremarkable. Over the next several months, he gained approximately 35 pounds (∼16 kg). It was in the setting of weight gain that he was first evaluated for hypercortisolism with random serum cortisol of 22.8 mcg/dL (629 nmol/L) and 45.6 mcg/dL (1258 nmol/L) in the late morning and mid-day, respectively. No reference range was provided for the times of day at which these laboratory values were drawn. Although these serum cortisol values were above provided reference ranges for other times of day, they were not flagged as abnormal by in-house laboratory convention, and they were overlooked. The search for other etiologies of his symptoms continued.

In early 2021, diuretic therapy and potassium supplementation were escalated for anasarca. He developed lower extremity cellulitis and received multiple courses of antibiotics. Skin biopsy performed by dermatology demonstrated disseminated Mycobacterium and later Serratia (2), prompting referral to infectious disease for management. Additional subspecialty referrals included rheumatology (polyarthralgia) and gastroenterology (mildly elevated alanine transaminase with planned liver biopsy). In July 2021, he was evaluated for edema by nephrology, where the constellation of subjective symptoms and objective data including hypertension, central weight gain, abdominal striae, fracture, edema, easy bruising, medication-induced hypokalemia, atypical infections, and high afternoon serum cortisol were noted, and the diagnosis of Cushing syndrome was strongly suspected. Emergent referral to endocrinology was placed.

Diagnostic Assessment

At his first clinic visit with endocrinology in June 2021, the patient’s blood pressure was well-controlled on benazepril. Following weight gain of 61 pounds (∼28 kg) in the preceding 2 years, body mass index was 33. Physical examination demonstrated an ill-appearing gentleman with dramatic changes when compared to prior pictures (Fig. 2), including moon facies, dorsocervical fat pad, violaceous abdominal striae, weeping lower extremity skin infections, an inability to stand without assistance from upper extremities, and depressed mood with tangential thought processes.

Figure 2.

Photographic representation of physical changes during the years leading up to diagnosis of ectopic Cushing syndrome in June 2021 and after surgical resection of culprit lesion.

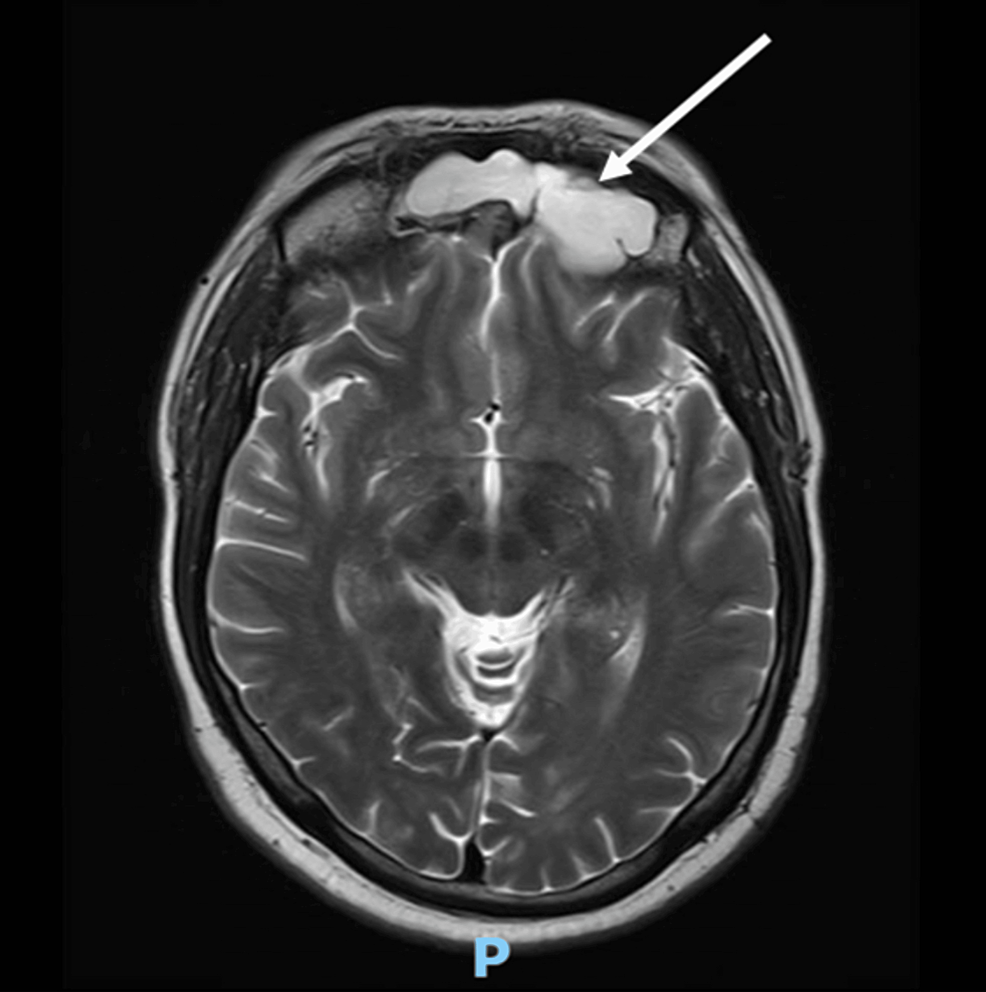

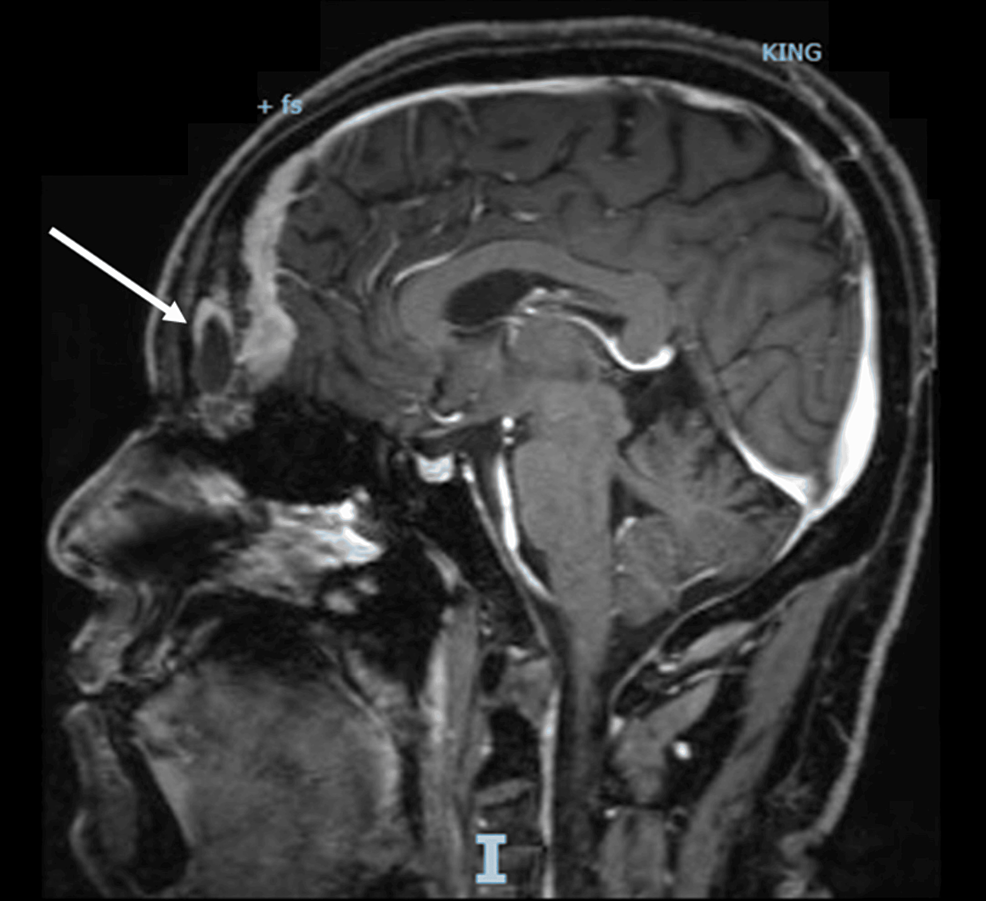

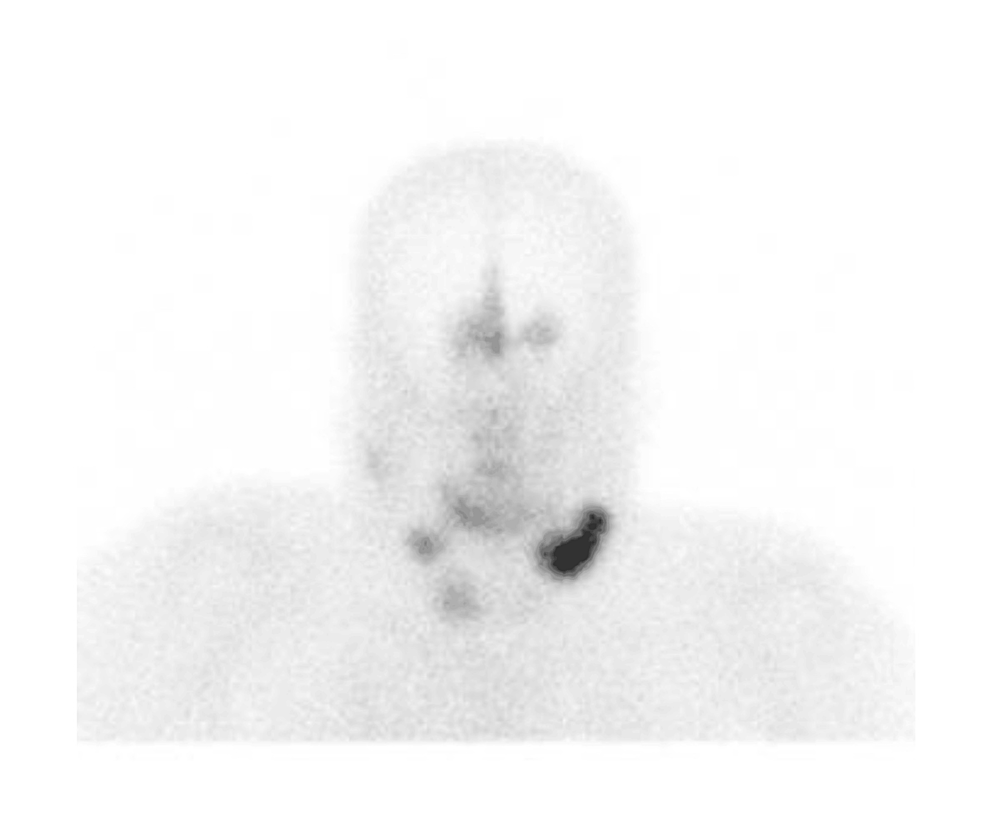

Diagnostic workup for hypercortisolism included a morning cortisol of 33.4 mcg/dL (922 nmol/L) (normal reference range, 4.5-22.7 mcg/dL) and ACTH of 156 pg/mL (34 pmol/L) (normal reference range, 7.2-63 pg/mL) following bedtime administration of 1-mg dexamethasone, and 24-hour urine free cortisol of 267 mcg/24 hours (737 nmol/24 hours) (normal reference range, 3.5-45 mcg/24 hours). Morning serum cortisol and plasma ACTH following bedtime administration of 8-mg dexamethasone were 27.9 mcg/dL (770 nmol/L) and 98 pg/mL (22 pmol/L), respectively. Given concern for potential decompensation, he was hospitalized for expedited work-up. Brain MRI did not demonstrate a pituitary lesion (Fig. 3), and inferior petrosal sinus sampling under desmopressin stimulation showed no central-to-peripheral gradient (Table 1). He underwent a positron emission tomography–computed tomography 68Ga-DOTATATE scan that demonstrated a 1.2-cm left pulmonary nodule with radiotracer uptake (Fig. 4).

Figure 3.

A, Precontrast and B, postcontrast T1-weighted sagittal magnetic resonance imaging of the sella. Images were affected by significant motion degradation, precluding clear visualization of the pituitary gland on coronal imaging.

Figure 4.

68Ga-DOTATATE imaging. A, Coronal and B, axial views of the chest after administration of radiopharmaceutical. Arrow in both panels indicates DOTATATE-avid 1.2-cm left lung lesion.

Table 1.

Bilateral petrosal sinus and peripheral adrenocorticotropin levels preintravenous and postintravenous injection of desmopressin acetate 10 mcg

| Time post DDAVP, min |

Left petrosal ACTH |

Left petrosal:peripheral ACTH |

Right petrosal ACTH |

Right petrosal:peripheral ACTH |

Peripheral ACTH |

Left:right petrosal ACTH |

| 0 |

172 pg/mL

(37.9 pmol/L) |

1.1 |

173 pg/mL

(38.1 pmol/L) |

1.2 |

150 pg/mL

(33.0 pmol/L) |

1.0 |

| 3 |

288 pg/mL

(63.4 pmol/L) |

1.8 |

292 pg/mL

(64.3 pmol/L) |

1.8 |

162 pg/mL

(35.7 pmol/L) |

1.0 |

| 5 |

348 pg/mL

(76.6 pmol/L) |

1.8 |

341 pg/mL

(75.1 pmol/L) |

1.8 |

191 pg/mL

(42.1 pmol/L) |

1.0 |

| 10 |

367 pg/mL

(80.8 pmol/L) |

1.3 |

375 pg/mL

(82.6 pmol/L) |

1.3 |

278 pg/mL

(61.2 pmol/L) |

1.0 |

Abbreviations: ACTH, adrenocorticotropin; DDAVP, desmopressin acetate.

Treatment

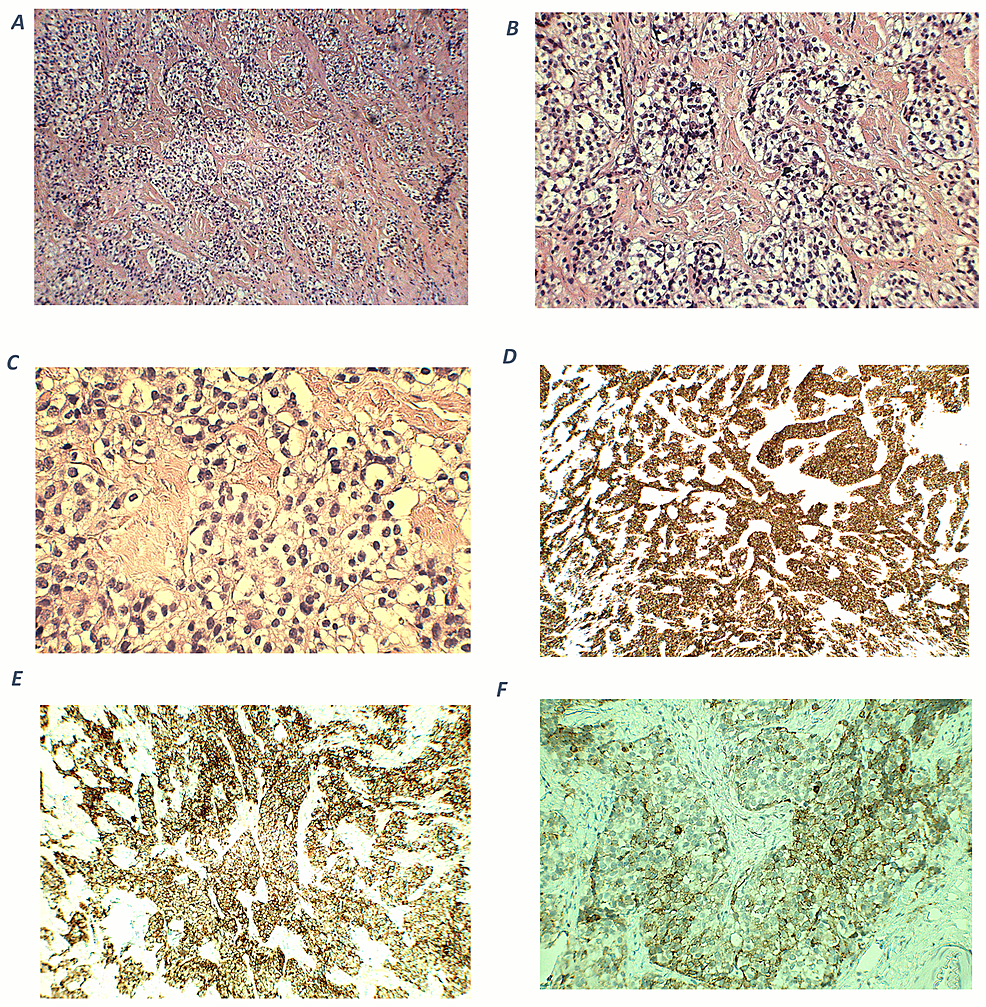

The patient was started on ketoconazole 200 mg daily for medical management of ectopic ACTH-induced hypercortisolism while awaiting definitive surgical treatment. Within a month of initial endocrinology evaluation, he underwent thoracoscopic left upper lobe wedge resection with intraoperative frozen histopathology section consistent with a well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumor and final pathology consistent with a well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumor. Staining for ACTH was positive (Fig. 5). Postoperative day 1 morning cortisol was 1.4 mcg/dL (39 nmol/L) (normal reference range, 4.5-22.7 mcg/dL). He was started on glucocorticoid replacement with hydrocortisone and was discharged from his surgical admission on hydrocortisone 40 mg in the morning and 20 mg in the afternoon.

Figure 5.

Lung tumor histopathology. A, The tumor was epicentered around a large airway (asterisk) and showed usual architecture for carcinoid tumor. B, The tumor cells had monomorphic nuclei with a neuroendocrine chromatin pattern, variably granulated cytoplasm, and a delicate background vascular network. By immunohistochemistry, the tumor cells were strongly positive for C, synaptophysin; D, CAM5.2; and E, adrenocorticotropin. F, Ki-67 proliferative index was extremely low (<1%).

Outcome and Follow-up

Approximately 12 days after discharge, the patient was briefly readmitted from the skilled nursing facility where he was receiving rehabilitation due to a syncopal event attributed to hypovolemia. This was felt to be secondary to poor oral intake in the setting of both antihypertensive and diuretic medications as well as an episode of emesis earlier in the morning precluding absorption of his morning hydrocortisone dose. Shortly after this overnight admission, he was discharged from his skilled nursing facility to home. In the first month after surgery, he lost approximately 30 pounds (∼14 kg) and had improvements in sleep and mood.

Eight months after surgery, hydrocortisone was weaned to 10 mg daily. Cosyntropin stimulation testing holding the morning dose showed 1 hour cortisol 21.5 mcg/dL (593 nmol/L). Hydrocortisone was subsequently discontinued. In June 2022, 1 year following surgery, 3 sequential midnight salivary cortisol tests were undetectable. At his last visit with endocrinology in June 2023, he felt well apart from ongoing neuropathic pain in his feet and continued but improved mood disturbance. Though his health has improved dramatically, he continues to attribute his divorce and substantial life disruption to his undiagnosed hypercortisolism.

Discussion

Endogenous neoplastic hypercortisolism encompasses a clinical spectrum from subclinical disease, as is common in benign adrenal cortical adenomas, to overt Cushing syndrome of adrenal, pituitary, and ectopic origin presenting with dramatic clinical manifestations (3) and long-term implications for morbidity and mortality (4). Even in severe cases, a substantial delay in diagnosis is common. In this case, despite marked hypercortisolism secondary to ectopic ACTH syndrome, the patient’s time from first symptoms to diagnosis was more than 3 years, far in excess of the typical time to diagnosis in this subtype, noted to be 14 months in 1 study (1).

He initially described a constellation of somatic symptoms including subjective neck swelling, axillary and inguinal soreness, chest discomfort, and paresthesias, and during the year preceding diagnosis, he developed hypertension, fibular fracture, mood changes, weight gain, peripheral edema, hypokalemia, unusual infections, and abdominal striae. Each of these symptoms in isolation is a common presentation in the primary care setting, therefore the challenge arises in distinguishing common, singular causes from rare, unifying etiologies, especially given the present epidemics of diabetes, obesity, and associated cardiometabolic abnormalities. By Endocrine Society guidelines, the best discriminatory features of Cushing syndrome in the adult population are facial plethora, proximal muscle weakness, abdominal striae, and easy bruising (5). Furthermore, Endocrine Society guidelines suggest evaluating for Cushing disease when consistent clinical features are present at a younger-than-expected age or when these features accumulate and progress, as was the case with our patient (5).

However, even when the diagnosis is considered, the complexities of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis make selection and interpretation of screening tests challenging outside the endocrinology clinic. We suspect that in most such situations, a random serum cortisol measurement is far more likely to be ordered than a validated screening test, such as dexamethasone suppression testing, urine free cortisol, and late-night salivary cortisol per Endocrine Society guidelines (5). Although random serum cortisol values are not considered a screening test for Cushing syndrome, elevated values can provide a clue to the diagnosis in the right clinical setting. In this case, 2 mid-day serum cortisols were, by in-house laboratory convention, not flagged as abnormal despite the fact that they were above the upper limit of provided reference ranges. We suspect that the lack of electronic medical record flagging of serum cortisol values contributed to these values being incorrectly interpreted as ruling out the diagnosis.

Cushing syndrome remains among the most evasive and difficult diagnoses in medicine due to the doubly difficult task of considering the disorder in the face of often protean signs and symptoms and subsequently conducting and interpreting screening tests. The challenges this presents for the nonendocrinologist have recently been recognized by a group in the United Kingdom after a similarly overlooked case (6). We believe that our case serves as a vivid illustration of the diagnostic hurdles the clinician faces and as a cautionary tale with regard to the potential downstream effects of a delay in diagnosis. Standardization of clinical laboratory practices in flagging abnormal cortisol values is one such intervention that may aid the busy clinician in more efficiently recognizing laboratory results suggestive of this diagnosis. While false-positive case detection is a significant downside to this approach, given the potential harm in delayed or missed diagnosis, the potential benefits may outweigh the risks.

Learning Points

- People with Cushing syndrome frequently experience a prolonged time to diagnosis, in part due to lack of recognition in the primary care and nonendocrine subspecialty settings of the constellation of clinical findings consistent with hypercortisolism.

- Endocrine Society guidelines recommend against random serum cortisol as initial testing for Cushing syndrome in favor of dexamethasone suppression testing, urine free cortisol, and late-night salivary cortisol.

- Increased awareness of Cushing syndrome by primary care providers and specialists in other fields could be an important and impactful mechanism to shorten the duration of symptom duration in the absence of diagnosis and hasten cure where cure is achievable.

- We suggest clinical laboratories consider standardizing flagging abnormal cortisol values to draw attention to ordering providers and perhaps lower the threshold for endocrinology referral if there is any uncertainty in interpretation, especially in the context of patients with persistent symptoms and elusive diagnoses.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to the patient for allowing us to present his difficult case to the community with the hopes of improving time to diagnosis for patients with hypercortisolism.

Contributors

All authors made individual contributions to authorship. J.M.E., E.M.Z., and K.R.K. were involved in the diagnosis and management of this patient. B.C.M., J.M.E., E.M.Z., and K.R.K. were involved in manuscript submission. S.M.J. performed and analyzed histopathology and prepared the figure for submission. All authors reviewed and approved the final draft.

Funding

No public or commercial funding.

Disclosures

J.M.E. was on the editorial board of JCEM Case Reports at the time of initial submission.

Informed Patient Consent for Publication

Signed informed consent obtained directly from the patient.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no data sets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

References

1

Rubinstein

G

,

Osswald

A

,

Hoster

E

, et al.

Time to diagnosis in Cushing’s syndrome: a meta-analysis based on 5367 patients

.

J Clin Endocrinol Metab

.

2020

;

105

(

3

):

dgz136

.

2

Park

MA

,

Gaghan

LJ

,

Googe

PB

,

Klein

KR

,

Mervak

JE

.

Disseminated cutaneous Mycobacterium chelonae infection as a presenting sign of ectopic adrenocorticotropic hormone syndrome

.

JAAD Case Rep

.

2021

;

18

:

79

‐

81

.

3

Reincke

M

,

Fleseriu

M

.

Cushing syndrome: a review

.

JAMA

.

2023

;

330

(

2

):

170

‐

181

.

4

Puglisi

S

,

Perini

AME

,

Botto

C

,

Oliva

F

,

Terzolo

M

.

Long-term consequences of Cushing’s syndrome: a systematic literature review

.

J Clin Endocrinol Metab

. 2024;

109

(

3

):

e901

‐

e909

.

5

Nieman

LK

,

Biller

BMK

,

Findling

JW

, et al.

The diagnosis of Cushing’s syndrome: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline

.

J Clin Endocrinol Metab

.

2008

;

93

(

5

):

1526

‐

1540

.

6

Scoffings

K

,

Morris

D

,

Pullen

A

,

Temple

S

,

Trigell

A

,

Gurnell

M

.

Recognising and diagnosing Cushing’s syndrome in primary care: challenging but not impossible

.

Br J Gen Pract

.

2022

;

72

(

721

):

399

‐

401

.

Abbreviations

-

ACTH

-

MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

© The Author(s) 2024. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the Endocrine Society.

This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs licence (

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits non-commercial reproduction and distribution of the work, in any medium, provided the original work is not altered or transformed in any way, and that the work is properly cited. For commercial re-use, please contact journals.permissions@oup.com

Filed under: Cushing's, Diagnostic Testing, Rare Diseases | Tagged: 68Ga-DOTATATE scan, dexamethasone suppression test, ectopic, Ectopic Cushing’s syndrome, lung | Leave a comment »