By Yolanda Smith, BPharm

Hypopituitarism is a health condition in which there is a reduction in the production of hormones by the pituitary gland.

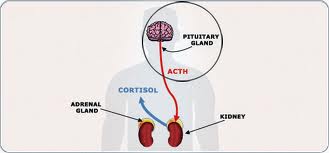

The pituitary gland is located at the base of the brain and is responsible for the production of several hormones, including:

- Adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), which controls the production of the vital stress hormones cortisol and dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) in the adrenal gland

- Thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), which controls the production of hormones by the thyroid gland

- Luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), which control the secretion of the primary sex hormones and affect fertility

- Growth hormone (GH), which regulates the growth processes in childhood and other metabolic processes throughout life

- Prolactin (PRL), which facilitates the production of breast milk

- Oxytocin, which is crucial during labor, childbirth and lactation

- Antidiuretic hormone (ADH), also known as vasopressin, which regulates the retention of water and the blood pressure

An individual with hypopituitarism shows a deficiency in one or more of these hormones. This inevitably leads to abnormal body function, as an effect of the low levels of the hormone in the body, and may result in symptoms.

Causes

Hypopituitarism is most commonly due to the destruction, compression or inflammation of pituitary tissue by a brain tumor in that region. Other causes include:

- Head injury

- Infections such as tuberculosis

- Ischemic or infarct injury

- Radiation injury

- Congenital and genetic causes

- Infiltrative diseases such as sarcoidosis

Symptoms

General symptoms that are associated with pituitary hormone deficiency include:

- Weakness and fatigue

- Decreased appetite

- Weight loss

- Sensitivity to cold

- Swollen facial features or body

There are also likely to be more specific symptoms according to the type of pituitary hormone deficiency, such as:

- ACTH deficiency:

- abdominal pain

- low blood pressure

- low serum sodium levels

- skin pallor

- TSH deficiency:

- generalized body puffiness

- sensitivity to cold

- constipation

- impaired memory and concentration

- dry skin

- anemia

- LH and FSH deficiency:

- reduction in libido

- erectile dysfunction in men

- abnormal menstrual periods

- vaginal dryness in women

- difficulty in conceiving

- infertility.

- GH deficiency:

- slow growth

- short height

- an increase in body fat

Treatment

The first step in the treatment of hypopituitarism is to identify the cause of the condition.

Secondly, the hormones that are deficient must be identified. From this point, the appropriate treatment decisions can be made to promote optimal patient outcomes.

Hormone replacement therapy is the most common type of treatment for a patient with hypopituitarism.

This may involve supplementation of one or more hormones that are deficient, to reduce or correct the impact of the deficiency.

Follow Up

As hormone replacement therapy is expected to continue on a lifelong basis, it is important that patients have a good understanding of the therapy.

It is especially important to educate patients on what to do in case of particular circumstances that may change their hormone requirements.

For example, during periods of high stress, the demand for many hormones is increased, and the dose of hormone replacement may need to be adjusted accordingly.

It is recommended that patients have regular blood tests to monitor their hormone levels and ensure that they are in the normal range.

Patients should also carry medical identification, such as a medical bracelet or necklace, to show that they are affected by hypopituitarism and inform others about their hormone replacement needs and current treatment. This can help to meet their medical needs in case of any emergency.

Epidemiology

Hypopituitarism is a rare disorder that affects less than 200,000 individuals in the United States, with an incidence of 4.2 cases per 100,000 people per year.

The incidence is expected to be higher in certain subsets of the population, such as those that have suffered from a brain injury. Statistics in reference to these population groups have not yet been determined.

Reviewed by Dr Liji Thomas, MD.

References

- https://pituitarysociety.org/patient-education/pituitary-disorders/hypopituitarism/what-is-hypopituitarism

- http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/122287-overview#showall

- http://patient.info/doctor/hypopituitarism-pro

- http://www.nytimes.com/health/guides/disease/hypopituitarism/overview.html

- http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/hypopituitarism/home/ovc-20201485

From http://www.news-medical.net/health/Hypopituitarism-Deficiency-in-Pituitary-Hormone-Production.aspx

Filed under: pituitary | Tagged: ACTH, ADH, Adrenocorticotropic hormone, Antidiuretic hormone, cortisol, Dehydroepiandrosterone, DHEA, FSH, GH, growth hormone, hormones, hypopituitarism, Luteinizing Hormone, Oxytocin, pituitary, PRL, prolactin, Thyroid-stimulating hormone, TSH | Leave a comment »