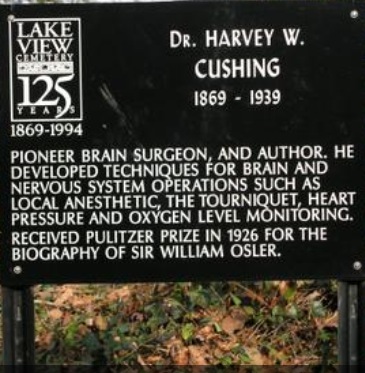

(BPT) – More than 80 years ago renowned neurosurgeon, Dr. Harvey Cushing, discovered a tumor on the pituitary gland as the cause of a serious, hormone disorder that leads to dramatic physical changes in the body in addition to life-threatening health concerns. The discovery was so profound it came to be known as Cushing’s disease. While much has been learned about Cushing’s disease since the 1930s, awareness of this rare pituitary condition is still low and people often struggle for years before finding the right diagnosis.

Read on to meet the man behind the discovery and get his perspective on the present state of Cushing’s disease.

* What would Harvey Cushing say about the time it takes for people with Cushing’s disease to receive an accurate diagnosis?

Cushing’s disease still takes too long to diagnose!

Despite advances in modern technology, the time to diagnosis for a person with Cushing’s disease is on average six years. This is partly due to the fact that symptoms, which may include facial rounding, thin skin and easy bruising, excess body and facial hair and central obesity, can be easily mistaken for other conditions. Further awareness of the disease is needed as early diagnosis has the potential to lead to a more favorable outcome for people with the condition.

* What would Harvey Cushing say about the advances made in how the disease is diagnosed?

Significant progress has been made as several options are now available for physicians to use in diagnosing Cushing’s disease.

In addition to routine blood work and urine testing, health care professionals are now also able to test for biochemical markers – molecules that are found in certain parts of the body including blood and urine and can help to identify the presence of a disease or condition.

* What would Harvey Cushing say about disease management for those with Cushing’s disease today?

Patients now have choices but more research is still needed.

There are a variety of disease management options for those living with Cushing’s disease today. The first line and most common management approach for Cushing’s disease is the surgical removal of the tumor. However, there are other management options, such as medication and radiation that may be considered for patients when surgery is not appropriate or effective.

* What would Harvey Cushing say about the importance of ongoing monitoring in patients with Cushing’s disease?

Routine check-ups and ongoing monitoring are key to successfully managing Cushing’s disease.

The same tests used in diagnosing Cushing’s disease, along with imaging tests and clinical suspicion, are used to assess patients’ hormone levels and monitor for signs and symptoms of a relapse. Unfortunately, more than a third of patients experience a relapse in the condition so even patients who have been surgically treated require careful long-term follow up.

* What would Harvey Cushing say about Cushing’s disease patient care?

Cushing’s disease is complex and the best approach for patients is a multidisciplinary team of health care professionals working together guiding patient care.

Whereas years ago patients may have only worked with a neurosurgeon, today patients are typically treated by a variety of health care professionals including endocrinologists, neurologists, radiologists, mental health professionals and nurses. We are much more aware of the psychosocial impact of Cushing’s disease and patients now have access to mental health professionals, literature, patient advocacy groups and support groups to help them manage the emotional aspects of the disease.

Learn More

Novartis is committed to helping transform the care of rare pituitary conditions and bringing meaningful solutions to people living with Cushing’s disease. Recognizing the need for increased awareness, Novartis developed the “What Would Harvey Cushing Say?” educational initiative that provides hypothetical responses from Dr. Cushing about various aspects of Cushing’s disease management based on the Endocrine Society’s Clinical Guidelines.

For more information about Cushing’s disease, visit www.CushingsDisease.com or watch educational Cushing’s disease videos on the Novartis YouTube channel at www.youtube.com/Novartis.

Filed under: Cushing's, pituitary, Rare Diseases | Tagged: 24-hour urine free cortisol test, blood tests, Cushing's Disease, Dr. Harvey Cushing, easy bruising, endocrinologist, facial rounding, hirsuitism, moonface, neurologist, neurosurgeon, obesity, pituitary, radiologist, recurrence, relapse, research, surgery, thin skin, tumor, UFC, urine free cortisol | Leave a comment »