Transsphenoidal surgery — a minimally invasive surgery for removing pituitary tumors in Cushing’s disease patients — is also effective in children and adolescents with the condition, leading to remission with a low rate of complications, a study reports.

The research, “Neurosurgical treatment of Cushing disease in pediatric patients: case series and review of literature,” was published in the journal Child’s Nervous System.

Transsphenoidal (through the nose) pituitary surgery is the main treatment option for children with Cushing’s disease. It allows the removal of pituitary adenomas without requiring long-term replacement therapy, but negative effects on growth and puberty have been reported.

In the study, a team from Turkey shared its findings on 10 children and adolescents (7 females) with the condition, who underwent microsurgery (TSMS) or endoscopic surgery (ETSS, which is less invasive) — the two types of transsphenoidal surgery.

At the time of surgery, the patients’ mean age was 14.8 years, and they had been experiencing symptoms for a mean average of 24.2 months. All but one had gained weight, with a mean body mass index of 29.97.

Their symptoms included excessive body hair, high blood pressure, stretch marks, headaches, acne, “moon face,” and the absence of menstruation.

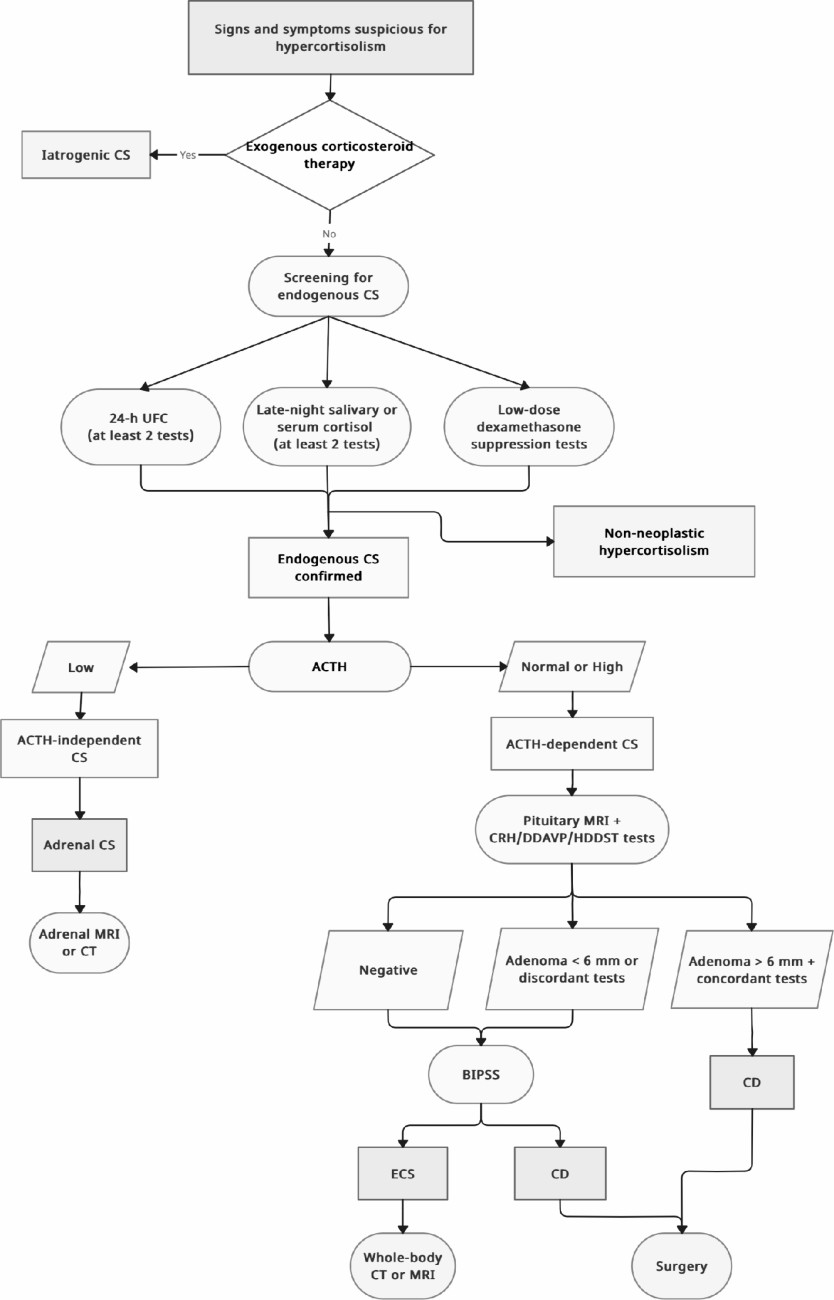

The patients were diagnosed with Cushing’s after their plasma cortisol levels were measured, and there was a lack of cortical level suppression after they took a low-dose suppression treatment. Measurements of their adrenocorticotropic (ACTH) hormone levels then revealed the cause of their disease was likely pituitary tumors.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans, however, only enabled tumor localization in seven patients: three with a microadenoma (a tumor smaller than 10 millimeters), and four showed a macroadenoma.

CD diagnosis was confirmed by surgery and the presence of characteristic pituitary changes. The three patients with no sign of adenoma on their MRIs showed evidence of ACTH-containing adenomas on tissue evaluation.

Eight patients underwent TSMS, and 2 patients had ETSS, with no surgical complications. The patients were considered in remission if they showed clinical adrenal insufficiency and serum cortisol levels under 2.5 μg/dl 48 hours after surgery, or a cortisol level lower than 1.8 μg/dl with a low-dose dexamethasone suppression test at three months post-surgery. Restoration of normal plasma cortisol variation, eased symptoms, and no sign of adenoma in MRI were also requirements for remission.

Eight patients (80%) achieved remission, 4 of them after TSMS. Two patients underwent additional TSMS for remission. Also, 1 patient had ETSS twice after TSMS to gain remission, while another met the criteria after the first endoscopic surgery.

The data further showed that clinical recovery and normalized biochemical parameters were achieved after the initial operation in 5 patients (50%). Three patients (30%) were considered cured after additional operations.

The mean cortisol level decreased to 8.71 μg/dl post-surgery from 23.435 μg/dl pre-surgery. All patients were regularly evaluated in an outpatient clinic, with a mean follow-up period of 11 years.

Two patients showed pituitary insufficiency. Also, 2 had persistent hypocortisolism — too little cortisol — one of whom also had diabetes insipidus, a disorder that causes an imbalance of water in the body. Radiotherapy was not considered in any case.

“Transsphenoidal surgery remains the mainstay therapy for CD [Cushing’s disease] in pediatric patients as well as adults,” the scientists wrote. “It is an effective treatment option with low rate of complications.”

Filed under: Cushing's, pituitary, Treatments | Tagged: children, Cushing's Disease, dexamethasone suppression test, diabetes insipidus, endoscopic, hypocortisolism, pituitary, pituitary insufficiency, remission, Transsphenoidal surgery, treatment | Leave a comment »